April Third Movement

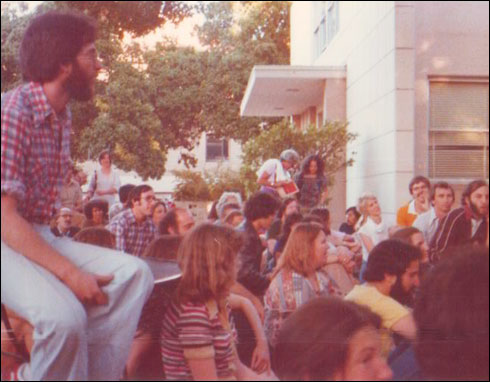

1979 A3M Reunion

Time warp—just like any other reunion, but not quite.

At how many reunions do the participants tour the buildings they trashed, sat-in at and took over, only to adjourn to Columbae House to look at news clips of a demonstration in which they were tear-gassed?

At how many reunions in Bowman Oak Grove do the alums reminisce about the time they disrupted a Board of Trustees' meeting at the nearby Faculty Club and ate the trustees' eclairs? Not many. But this one was Saturday's 10-year get-together of 125 members of the April 3 Movement (A3M), a group of people from the University who sat in at the Applied Electronics Laboratories (AEL), took over Encina Hall and demonstrated at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) in the spring of 1969.

The issues were the University's involvement in the Vietnam War effort, and in a larger sense, the war as a whole.

As Stewart Burns, now an activist in the Abalone Alliance, an anti-nuclear group, said, "There was a feeling that we had to stop the war in very concrete terms. We were also trying to build a movement to stop the war."

An ex-protester who asked not to be named added that "SRI was a minor question, but it was a focus" around which to promote the anti-war movement in general.

The A3M began on April 3, 1969, when more than 300 persons met in Dinkelspiel Auditorium and voted to demand that SRI be brought under tighter University control. One week later, hundreds of students sat-in at AEL to prevent the continuation of war-related research there.

"The research at SRI and AEL was crucial to the war," Burns said. "There is some evidence that research was going on at AEL on smart bombs used in 1972 against the North Vietnamese offensive."

The Academic Council voted a week later to end many kinds of secret research at the University, including some that was being conducted at AEL, but controversy continued over SRI and its ties to the University.

A trustee committee met on campus with student representatives. Many students who watched the meeting over closed-circuit television in Memorial Auditorium walked out. After several hours of discussion they took over Encina Hall early on the morning of May 1. They left that morning under threat of arrest. Many were later suspended.

The trustees, however, severed University ties with SRI instead of tightening them as the A3M members demanded. More than 400 students subsequently blocked roads near the SRI building in the Stanford Industrial Park and were dispersed by police using tear gas.

But what did the trials and tribulations of the protests achieve? Doron Weinberg was then a teaching fellow at the Law School, a prominent member of A3M and moderator of many of the mass meetings. He pointed both to the end of the war and additions to "the political lexicon" over the past 10 years. The range of "what people consider legitimate political opinion has increased," he said.

He added that the Vietnam War and public reaction to it helped limit U.S. options for international involvement. He mentioned Angola and Iran as places where U.S. action may have been deterred by the scars of the Indochina experience.

Phil Trounstine, now a reporter for the San Jose Mercury, was more pessimistic about the movement's impact on the University.

"I think Stanford is right back where it was 10 years ago," he said. "I don't think Stanford has much more of a moral conscience now."

Paul Rupert, now an administrator in San Francisco, said he feels that circumstances have changed in other ways, too. He said that when he was a freshman here in 1963, Stanford was a country club.

"The strangest part is that it is amazingly more of one now. It's reverting with a vengeance" to what it was like then, he said.

People who were part of the A3M still have a lot of political and social consciousness, Rupert added.

Trounstine said most people "still have the same set of social beliefs and have found new ways of doing what they feel is socially beneficial. People still have the anti-imperialist attitude the A3M spawned and nurtured."

Weinberg, though, noted a distinct difference between activism then and now. He said that now, “the causes are more diffuse. The raw numbers of people somehow involved (politically active) are at least as great," but they are not all concerned with the same issue as people were with Vietnam.

But on Saturday, everybody was concerned with the Vietnam War once again, and with their roles in protesting it.

Lenny Siegel, another A3M member was characterized as the "big brother, welcome-to-the movement radical." He recalled a saying that originated when Durand Building was repeatedly trashed — "People who do war research shouldn't live in glass buildings."

Siegel said he never registered at the University after the trustee disruption incident. "I've always wanted to finish Stanford, but it's still here," he said.

Other people had their share of reminiscences to contribute, too.

"Remember the time the police were watching us from a helicopter and we spelled out 'FUCK YOU' in drill formation?"

According to a list of addresses and occupations compiled by the sponsor of the reunion, the Pacific Studies Center (PSC), the most common occupation of A3M veterans who attended the reunion is law. One-sixth of them are lawyers. The next most common professions are writers and reporters, followed by natural scientists, academicians and administrators.

Most of the ex-protesters on the PSC list still live in the area, one-third of them in the south peninsula and another third in the rest of the Bay Area. Fifteen percent live in the East, and 10 percent in the rest of California.

But statistics aside, the reunion was people coming together again. People watching the films of the demonstration at SRI and laughing and pointing at people they knew.

It was people talking about how getting the invitation to the reunion made them feel very old, people rehashing the protests and people like Siegel, saying that they look back fondly on the days of student activism that shaped their lives.