April Third Movement

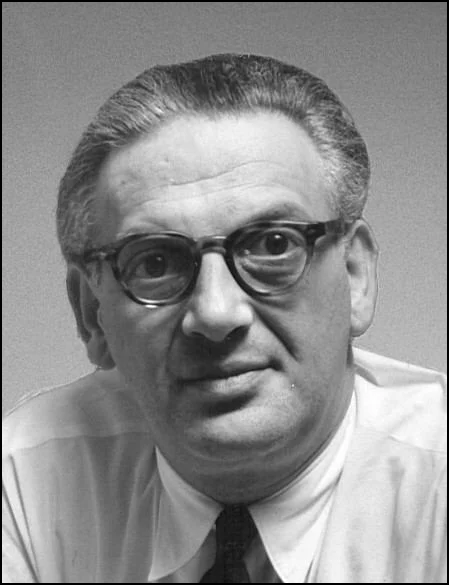

Paul Alexander Baran

Economist–Thinker Baran Dies

Last Thursday Paul A. Baran, professor of economics, suffered a heart attack and died in San Francisco. The 53-year-old professor's sudden death was termed a "distinct loss to social thought in this country" by Dr. Moses Abromovitz, head of the Economics Department

Baran was one of the few experts on Marxist economic theory on the faculty of a major university. Formerly senior economist on the Federal Reserve Hank of New York, he was a specialist on economic policy for the underdeveloped nations.

Professor Baran was born in Russia in 1910 and studied in Europe and America, receiving his Master's degree from Harvard and his Doctorate from the University of Berlin. Since coming to Stanford in 1949, he has taught courses in economic history and comparative economics

In citing Baran as a "fighter for reason and justice," Dr. Abramovitz said, "He was one of the very few exponents of Marxism who held an official place in American academic life. As such he helped to keep economic thought in this country and other western countries in contact with an intellectual current which has shaken the world."

On April 2 at 8 p.m. in Cubberley Auditorium, there will be a panel discussion of the achievements that Baran accomplished. Professor Baran, who championed such liberal causes as the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, was respected as a social critic and leader of liberal thought.

Memorial Resolution: Paul A. Baran 1909–1964

Paul A. Baran was born at Nikolaev in the Southern Ukraine on August 25, 1909, a little over eight years before the Bolshevik Revolution that so profoundly affected his life and ideas. His father, then retired, was a physician who had been active in the Socialist Movement (as a Menshevik) prior to the Revolution of 1905 but had thereafter ceased political activity to concentrate on the practice of medicine. He maintained, however, a lively interest in political affairs which greatly influenced his son. This influence was enhanced by the fact that, because of ill health and the political turbulence of his childhood years, Paul had virtually no formal schooling until he entered a Gymnasium in Dresden at the age of 11.

The senior Baran took his family to Germany, with a brief stop at Vilna, in 1920. However, because of legal restrictions, he was unable to practice medicine in Germany and after a few years, decided to repatriate himself. But a good part of Paul's formative years, 1920-26, was spent in Germany. It was there that he became an active Socialist. From his early days at the Gymnasium, first in Dresden and later in Berlin, he participated actively in Socialist youth groups. His formal class work gave him a thorough grounding in the classics, but in his leisure time he studied Marxist doctrine and engaged in Socialist agitation.

After graduating from the Gymnasium in Berlin in 1926 he followed his parents back to Moscow, at whose University he studied for two years, receiving a Diploma in Economics in 1928. During these years he continued his active political work and was heavily engaged in the political struggles of this period as they were reflected in Communist youth organizations. Perceiving the trend of political events in 1928, he chose not to return from his summer vacation in Germany, but to remain there. From then until Hitler's accession to power he studied, engaged in left-wing Socialist politics, and eked out a livelihood as a research assistant and a journalist. During these years, he studied at the Universities of Frankfurt, Breslau and Berlin, receiving his Ph.D. from the last of these institutions in April 1933. Almost immediately thereafter he left Nazi Germany for Paris.

Paris offered him no employment opportunities and so in 1934, Baran once more returned to Russia. But the political climate was oppressive, and once again he had to leave, this time for over 20 years. He went first to his father's family in Vilna, and from there to Warsaw. Through his family connections he obtained a position as an economist with the local Chamber of Commerce. After two years, he went to London in 1937 as a sales representative of some timber firms and remained there until late 1939 when, determined to resume his intellectual career, he came to the United States. After a brief period as a part-time lecturer at the New School for Social Research, he went in the fall of 1940 to Harvard University which awarded him a M.A. in 1941. In 1942 he began a two and a half year stint as an economist with the Office of Strategic Services, after which he served for almost a year with the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey in Germany and Japan. Thereafter he attempted to launch a weekly magazine which he hoped would serve as an American parallel to the London Economist. When this failed for want of financial backing, he accepted a position as an economist with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (at the beginning of 1947) where he remained until he came to Stanford as an Associate Professor in 1949; in 1951 he was promoted to Professor.

The last 14 years of Baran's life were spent, save for occasional leaves of absence, as a professor at Stanford. In some ways these years were happy ones. He loved to teach; whether with small groups at coffee or in packed lecture halls, he was a star performer and reveled in the fact. His wit and lucidity brightened the murkiest corners of the dismal science

and attracted students in droves. His effectiveness as a teacher is suggested by his writing but can never be fully appreciated except by those who heard him. These pedagogical achievements were in a language that he made his own only after reaching maturity.

It is hardly necessary to add that these same qualities made him the most entertaining of companions and stimulating of colleagues. Of course, a biting wit combined with a strong propensity for serious political and philosophical debate does not make for placid personal relations. And Paul's relations with his colleagues were predictably turbulent. Yet, over the years, things were amicable more often than not. The reason was basically the symbiotic nature of the relationship between Paul and the other members of his department; he needed an audience of his peers, while they greatly prized the stimulus of his mind and the sparkle of his personality.

In his writing and research, Baran was not quite so happy. He was not overly blessed with perseverance, and the varied nature of his early career did little to build those habits of patient industry that are a necessary condition of scholarly output. Probably brilliance was the enemy of assiduity; for the few who can afford it, there is a great temptation to squander intellectual wealth in conspicuous conversation instead of accumulating it in published form.

This is not to suggest that Baran was obscure or unproductive; far from it. In his case, self- dissatisfaction was a measure of aspiration. His major work, The Political Economy of Growth, has been translated into eight languages and has sold well over 50,000 copies. Its ideas are known, admired and debated wherever economic growth is seriously studied. It gained its author large and enthusiastic audiences at universities in Chile, Argentina and Mexico as well as in the major countries of Europe. Indeed, in many places, not all in the Sino-Soviet world, Stanford is favorably known as the university at which Paul Baran is professor. He confidently expected that works virtually completed, and now to be published posthumously, would add to his fame. But for him, this was not enough.

Clearly, he believed he had not, and perhaps could not, display the full power of his mind in his writing. As he said only a few weeks ago, A thinker's quality is shown by the lightning flash with which he illuminates a field of ideas. The volume of his output measures only the extent of his neurosis.

As applied to himself, as he perhaps intended it should be, it is unquestionably true. Few minds, indeed, have possessed his incandescence, though many have turned out more pages.

Undoubtedly, some of the malaise stemmed from his dislike of academic specialization. He was a highly competent academic economist, though largely self-taught. Had he chosen, he could have parlayed his linguistic skills, native intelligence, and technical knowledge into an enormously successful professional career. But to do this he would have had to devote himself to the technical and necessarily specialized problems to which economics—like other disciplines—directs its attention. And this he refused to do.

In his own pungent phrase, he was no intellect worker

but an intellectual. The whole of human knowledge, or at least the part of it that relates to the history of human organizations, was his province. He recognized no boundaries separating the social sciences and the enormous range of his reading covered history, sociology, political science, and psychoanalysis quite as extensively as economics. In writing, as in reading, subject matter followed interest. As a result, his publications had far more appeal to non-economists than to his fellow professionals, and the esteem in which he was held outside his field of nominal specialization was correspondingly greater than inside. Though he understood the reason for this state of affairs, he found it galling, nonetheless.

Any account of Baran's later career must mention his continued adherence to the political tenets of his youth. He remained a Marxian socialist to the end, and proudly acknowledged the fact. He did not mind being in a small minority; as he said, "since Sweezy is the foremost Marxian economist in America, I am, ex definitione, the hindmost." Foremost or hindmost, he was surely the greatest exemplar of intellectual nonconformity Stanford has had since Thorstein Veblen and quite possibly the most penetrating critic of capitalism an American institution of higher learning has harbored since the sage of Cedro. It is to the fame of our University, and the great good fortune of its faculty and students, that it protected Baran's freedom to espouse his views despite heavy pressure to do otherwise. His passing may perhaps remove a thorn from its side, but it also takes a very bright star from its firmament—one that cannot be replaced.

Stolen Documents Chart Baran Affair in 1960s

Confidential administration documents, apparently stolen from sealed files in the University Archives, have revealed the stormy Stanford history of the late Paul Baran, a world-renowned Marxist economist.

The letters and memos are filled with alumni complaints and threats in reaction to the socialist views of Baran, who taught at Stanford from 1948 until his death in 1964.

Xerox copies of the documents, mailed anonymously to local newspapers, also document administrators' careful attempts to calm wealthy alumni. The officials referred to Baran as a thorn in the side

of Stanford but said he could not be fired because he was a tenured professor and had broken no rules Baran's son Nick, a sophomore in German, said he received the documents several weeks ago in an unmarked envelope.

The younger Baran said the documents showed administrators acted in an unprincipled way.

He said they wrote wishy-washy

letters which did not clearly defend academic freedom.

He compared pressures on Baran to current dismissal charges against Maoist Professor H. Bruce Franklin and said, "Stanford's attack on undesirable radicals is by no means a new one."

Administration documents in the file include letters from former-President Wallace Sterling, presidential assistant Frederic Glover, and former-Provost Frederick Terman. Glover and other officials who could be contacted verified letters attributed to them in the file, although they denounced the theft as immoral and an abuse of private correspondence.

Chief Librarian Ralph Hansen said a check yesterday revealed that a file on Baran was missing from a locked room in the Archives. He said the file was probably taken at least several months ago.

Glover said that the letters he wrote were written when "things were different." He added that the file included letters written "to personal friends without expecting to have to justify the personal views."

According to the documents, Glover predicted problems with Baran as early as 1954. He sent Sterling a copy of a petition which Baran signed in support of a radical school then facing McCarthy-era investigations. Glover's note to "Wally" warned that "Baran, being in the Econ Dept., may give us real trouble one day."

The real trouble began in 1960, when Baran visited Cuba and spoke glowingly of Fidel Castro's new regime. There were additional flare-ups of alumni anger when Baran denounced the US' Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 and the US blockade of Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.

The attacks did not end until Baran died after suffering his second heart attack in 1964. His son charged that the University's pressure was one of the main reasons for his poor health.

Reaction to Baran's support of Castro in 1961 included a letter to the editor of the Daily which former Trustee David Packard wrote but never sent to the newspaper. Packard, who is now Deputy Secretary of Defense, said that Baran and visiting colleague Paul Sweezy were "avowed Marxists" who had violated the principle that a professor should be a teacher, not an advocate.

Packard wrote that Trustees should reduce the salaries of Baran and Sweezy proportionate to the amount which can be clearly identified as having come from sources other than Capitalism which they wish to destroy.

He added that we would be delighted

to see the two professors go back to Cuba. He joked that they later could be bought back in exchange for a couple of Sunday Gardener's rototillers.

Glover sent Sterling a copy of Packard's abortive letter to the editor, with a note saying, I'm sure glad he didn't send it." He said the letter contained several paragraphs which "would have blown the place wide open.

(Packard was at the White House yesterday and could not be reached for comment.)

Other influential alumni also complained. Sterling heard from a recently retired Texaco Oil executive, who emphasized a $10,000 gift to Stanford from Texaco the year before. He commented that Baran's unqualified approval

of Castro seemed to endorse the Cuban seizure of Texaco's refineries there.

A response by University Relations official Donald Carlson told the executive that Baran was a distinguished scholar

but that "neither the University nor President Sterling endorse Professor Baran's views, of course."

Carlson's letter said that Communists are not permitted to hold positions on the Stanford faculty.

He said that Baran was a socialist but not a Communist.

Carlson commented yesterday that such comments must be put in the context of the '60s. This was the Birch time.

We wrote letters about Paul Baran for a long time—protecting him, of course, more than anything.

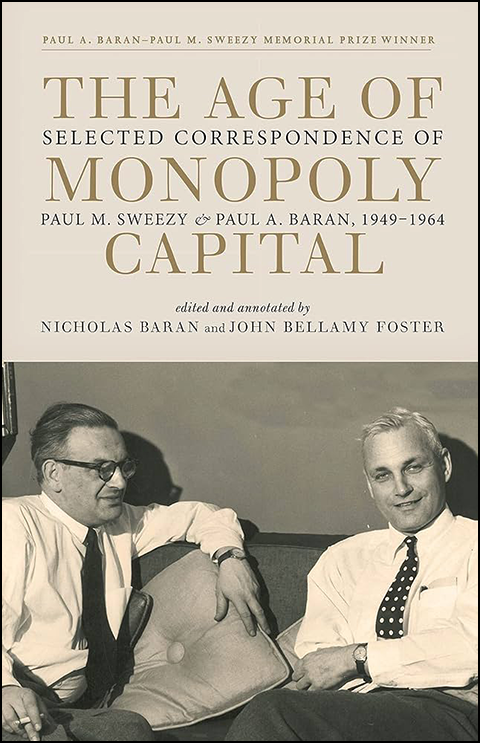

In June, 1963, Sterling wrote that CUBA, 1960—The late Paul Baran (second from left), a Marxist economist here through the early '60's, met Premier Fidel Castro in Cuba along with Paul Sweezy (left) with whom he wrote the book Monopoly Capital, and Leo Huberman (right) editor of Monthly Review. Baran continued to "do a good job of classroom teaching," the "critical" area in tenure questions. But expressing his personal weariness with Baran, Sterling said he wished that Baran and a supporter "would stick to their academic knitting and stay out of peripheral—and newsworthy—activities, legal as these may be."

(Sterling, who is currently recuperating from an illness, could not be reached for comment.)

Administrators repeatedly assured alumni that Baran only taught advanced-level courses. In Sterling's words, "Baran is not reaching many students."

A Glover letter in March, 1963, emphasized, "Baran has tenure. To fire him, we would have to have a reason which would stand up in court. And we don't have any such reason."

In the letter, Glover defended Baran's classroom performance as "provocative and interesting." He added that other professors did not agree with his views "and the students who do could meet in a phone booth." Glover added parenthetically, "And they would probably get the wrong number!"

When the criticism was booming, Sterling invited eight influential executives to a luncheon about the Baran affair at San Francisco's exclusive Pacific-Union Club.

Warm thank-you notes from guests indicated Sterling's success in placating the worried alumni.

Many of the complaints concerning Baran came from conservative alumni in the Los Angeles area. In March, 1963, a Los Angeles judge wrote Sterling that the issue was worrying potential contributors to the massive "PACE" fund-raising drive.

Baran had charged that his salary was "frozen" by the University to pressure him into resigning. The alumnus-judge, apparently agreeing with that analysis, suggested that Sterling send him Baran's salary and other information that would show Stanford "is doing all that it can to discourage him from remaining with the University."

However, Sterling refused to give such confidential information to fund-raisers.

The LA judge also warned Sterling that a friend had threatened to cut off his gifts because of Baran. He added that the angry man's will "provides that something in the neighborhood of a million dollars will go to Stanford upon his death."

The alumni complaints continued even after Baran's death. A Bakersfield businessman wrote to denounce a memorial tribute on campus. Glover, who yesterday said he helped plan the service, responded that "it is difficult as a practical matter to tell a dead man's friends that they cannot mourn him as they see fit."

Although the administration letters first became public this week, Baran knew of and criticized them when the conflict first began.

In a 1961 letter to Sweezy, he said that a friend had called the "standard" administration letter "despicable." Baran wrote, "It did not point out that the University was committed to the principle of academic freedom or anything of the sort but stressed it’s having the very difficult problem of my having tenure."

The Case Of Prof. Paul A. Baran

Editor's note: The following introduction was written to provide background information for a two-part opinion column starting today based on what appears to be a recently revealed University file on Paul Baran (see story page 1).

In its attempted purge of Bruce Franklin, Stanford is once again revealing a policy it pursued eight years ago, when the Sterling administration tried to eliminate Paul Baran.

Baran, a Marxist economist, taught at Stanford from 1949 until his death in 1964. When he publicly supported the Cuban revolution, Stanford froze his salary and increased his workload, moaning that he had done nothing to enable them to fire him outright. Neither the Economics Department nor the community at large defended Baran, and he felt alienated and alone. "If it weren't for my family, I would quit, literally tomorrow," he wrote a friend, “rather than have to tolerate those bastards spitting in my face all the time."

Born in the Ukraine in 1910, Baran was educated in Germany before WW 11. A member of the anti-fascist left, he helped smuggle Jews out of Germany until 1939. Baran came to the United States just before WW 11, and during the War he worked for the Office of Strategic Services as a specialist in Polish, German, and Soviet affairs. Immediately after the war, Baran held posts in the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey and at the Federal Reserve Bank in New York.

At Stanford Baran earned the reputation of being an exciting and stimulating teacher. Upwards of 150 people enrolled in some of his courses. With the publication of The Political Economy of Growth (1957) Marxists all over the world came to recognize Baran's work as fundamental to understanding underdevelopment and American imperialism. Business Week called him "the only Marxist professor on the faculty of a major U.S. university." His posthumously published book, Monopoly Capitalism (written with Paul Sweezy) has been translated into nine languages.

Strongly critical of American imperialism and of capitalist society generally, Baran was particularly disdainful of the social scientists whom he considered its agents. "Social scientists were assuring us that everything was fine," Baran wrote. But the opposite was true — "Idle men and idle machines coexist with depravation at home and starvation abroad. Poverty grows in step with affluence."

University professors— "intellect workers" not intellectuals — were "failing ever more glaringly to explain social reality." They were "the typical faithful servants, agents, and spokesmen of capitalist society." Allying themselves with the ruling class against workers, they "side with the social order which has given rise to their status and which has created their privileges."

In 1960, Fidel Castro invited Baran and Sweezy to Cuba. When Baran returned to Stanford, he immediately publicized his admiration for the Cuban revolution. The rural population had been "driven to revolt," he said, by the "increasingly insufferable state of poverty and backwardness to which it was condemned by the old order."

He was greatly impressed by the changes taking place in revolutionary Cuba. "We walked through abysmal quarters, in Santiago de Cuba where hovels, the horror and sordidness and misery of which are beyond my powers of description, are being torn down and replaced by colorful little houses." Cuba's poor, he said, were celebrating "the dramatic resurrection of their nation."

Baran was outraged with the Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis. "There is the frightful danger that American capitalism, cornered, threatened, and frightened, may be incapable of leaving the rest of the world alone without so slamming the door that the entire building collapses."

In fact, Baran predicted a frantic U.S.-led struggle against socialism in the Third World well before the escalation in Vietnam. "The real battlefields between capitalism and socialism have for years now been in Asia, Africa, and Latin America." There American imperialists would be involved "on an increasing scale" in the future.

To the men of wealth and power who consider Stanford their own turf, remarks like these were subversive and treasonous. The pace of letters pressuring Stanford to get rid of Baran increased rapidly. Administration action against Baran followed directly.

In a letter to Sweezy, Baran described the situation: "Had dinner with——. He was shown the whole mountain of correspondence that the administration received about you and me and Cuba. Apparently an impressive heap. He also saw the more or less standard letter which

"It did not point out that the University was committed to the principle of academic freedom or anything of the sort but stressed its having the very difficult problem of my having tenure. The business of freezing my salary, far from being treated as a secret, is being widely advertised to show that nothing would be done to “encourage me to stay here."

Baran added that the pressure and tension "bums me all up, plays havoc with the nervous system." In early 1964 he died of a heart attack.

The response to Baran's work has been quite a bit different in the Third World and among the New Left than from the men who run Stanford. After his death, Che Guevara wrote of "the admiration I felt for Companero Baran, as well as for his work on underdevelopment which was so constructive in our nascent and still weak state of knowledge of economics."

"Baran recaptured and preserved the idea of the scholar," wrote Herbert Marcuse. "For him there was no scholarship, no intelligence that was not radically critical of a social order that was organized to counteract the emergence of a humane society."

Bruce Franklin emerged as the leading radical intellectual at Stanford soon after Baran's death. There was no reason to doubt that he would suffer a fate much like Baran's. Franklin has certainly brought all sorts of threats from alumni, and the Lyman administration has worked hard to manufacture a case which would enable it to fire him legally, in keeping with alumni demands and its own liberal ideology.

Stanford is the slave of the trustees and its rich alumni. It is managed by the "intellect workers" who desire only to protect Stanford from revolutionary intellectuals who challenge the social order. The defense of stagnant conservatism, of meaningless inquiry into unimportant truths, and the attack on those who seek to discover the truths that reveal the corruption and injustice of this society are the main characteristics of the Stanford system.

There are no clearer examples of the victims of this system than Bruce Franklin and Paul Baran. (Nick Baran is Paul Baran's son, and a sophomore in German.)

Letters Expose Anti-Communist Policy

In the early 1960s Stanford found Marxist economist Paul A. Baran a considerable embarrassment

to the University. Wealthy and influential alumni demanded the outspoken professor be fired and threatened to cut off financial support.

Stanford had a policy that Communists are not permitted to hold positions on the Stanford faculty,

but because Baran said he was a socialist, not a communist, and because he had tenure, the Trustees felt we must suffer him

until he proved an incompetent teacher or does something which would warrant termination of his employment on other grounds.

Little or no effort was made to defend Baran's right to remain on the faculty in terms of academic freedom, and Deputy Secretary of Defense David Packard, then a Stanford Trustee, in an unpublished letter proposed that Baran's salary be reduced proportionate to the amount which can be clearly identified as having come from sources other than Capitalism.

These are some of the revelations contained in recently available Xerox copies of documents which come apparently from confidential files in the President's Office. The documents contain file copies of correspondence and memos written over the signatures of Presidential Assistant Fred O. Glover, Provost Emeritus Frederick Terman, Trustees David Packard and Morris Doyle, and of then President J.E. Wallace Sterling.

Many of the letters come from well-placed alumni complaining about Baran's public statements in favor of the Cuban revolution or denouncing U.S. foreign policy. The copies apparently do not represent a complete file.

While most of Stanford's embarrassment

with Baran seems to have come after his public support of the Cuban revolution, he was apparently a thorn in the Administration's flesh as early as 1954. Among the copied documents is an anti-communist publication critical of a petition signed by Baran and nearly 200 other educators supporting the left-wing Jefferson School of Social Sciences in New York (then under McCarthy Era attack by the Subversive Activities Control Board).

The only thing new in this is that it illustrates how long persisting is the backwash when someone signs one of these fool petitions,

is Fred Glover's penned comment. "Baran … may give us real trouble one day.

That day came in late 1960, apparently, when Baran and fellow economist Paul Sweezy visited Cuba at the invitation of Fidel Castro himself. On his return, Baran praised the Cuban revolution in a public lecture in Cubberley Auditorium. The Palo Alto Times quoted him as saying that Castro was "one of the greatest men of this century."

Nationally syndicated Hearst columnist Bob Considine picked up the story, connecting Baran with Stanford and calling him the newest cohort

in a small but articulate band

of American professors supporting Castro.

Apparently, these statements raised sufficient concern among influential alumni that Sterling decided to hold a private luncheon to discuss the situation. Among the copied documents is a guest list for the luncheon, held at the elite Pacific-Union Club in San Francisco March 6, 1961. Among the guests invited were top executives from Transamerica Corp., Standard Oil of California and California Casualty Indemnity Exchange.

At the luncheon, Sterling was apparently able to lay the alums' fears to rest. I am … most appreciative of hearing first-hand the situation at the Economics Department,

wrote one guest. Another wrote that as I reflected on … what you are trying to do to control this … matter, I came to the conclusion that you are doing a great deal and that your approaches were practical.

When Baran spoke out against the ClA's Bay of Pig's invasion of Cuba in mid-April, 1961, industrialist David Packard decided to enter the fray.

Stanford was then in an uproar over the Trustee's decision to make the Hoover Institution a semi-autonomous body under new director W. Glenn Campbell. Criticism was especially strong of ex-President Herbert Hoover's clearly political and overtly anti-communist revision of the Institution's governing purpose: to demonstrate the evils of the doctrines of Karl Marx.

Among the copied documents is an unpublished letter written by Packard to the Daily.

I am writing on the assumption that a Trustee enjoys the same right of free speech as a member of the faculty or a student, although the criticism of Mr. Hoover for expressing his opinion as to the purpose of the Hoover Institution would seem to question that assumption,

Packard wrote.

While Baran and Sweezy's Marxist thinking was their right and privilege,

Packard said, it is certainly a violation of the intellectual honesty expected of a Professor ….

Packard said that he intended to suggest to the Trustees that Baran and Sweezy's salaries be reduced proportionate to the amount which can be clearly identified as having come from sources other than Capitalism.

We would be delighted to have these men transfer their activities to Cuba,

Packard wrote. They could go with the assurance that if they … get into trouble we could get them back in exchange for a couple of tractors. In their case a couple of Sunday Gardener's rototillers would be about right.

Packard—or somebody in the President's Office—apparently had second thoughts about the letter, and it was never sent. I'm sure glad he didn't send it,

Glover penned Sterling. There are several other paragraphs which would have blown the place wide open, but the Hoover statement would have done all right on its own.

The sort of capitalism that paying Baran and Sweezy's salaries is disclosed among the copied documents in a letter from a Pasadena man who had retired some months earlier as an officer of Texaco. He enclosed a clipping from an apparently right-wing magazine, Facts in Education, titled Has Stanford No Shame?

and critical of Baran's support of Cuba.

The previous year, he reminded Sterling, Texaco had made Stanford a $10,000 gift. Since then, he said, the Cuban government had seized Texaco properties worth $50 million. The President's Office tried to calm the critic's anger and offer, perhaps, some consolation. University relations officer Don Carlson wrote that "barbed" questions had driven Baran into calling Castro one of the century's greatest men. I doubt if he enjoyed the harassment he has received because of it,

Carlson wrote. Shortly after that speech he had a serious heart attack.

Carlson tried to make University policy quite clear. I know that we would agree that Communism is the very antithesis of freedom, academic or otherwise,

q he wrote. This is why Communists are not permitted to hold positions on the Stanford faculty.

Baran was not a communist but a socialist, Carlson said.

The overwhelming majority of professors at this university are actively engaged in the explanation and repudiation of Communism and Marxist ideologies,

wrote University Relations officer Robert E. Miller, Jr., to another alum.

Baran's standing with the President's Office did not better when he spoke on Cuba in Los Angeles the night before the 1961 USC game. Apparently, several highly placed alums attended his talk and were not amused.

Among the copied documents is a letter from Stanford's Southern California public relations man to University Relations director Lyle Nelson saying that one couple who attended feel that Stanford has no business having a man like Baran on its faculty.

Their parents had given a dorm to Occidental College, he says, and it was hoped they were getting a possible interest in Stanford.

At the time, Daily editor Ron Rapoport was shown at least a portion of the University file on Baran, and in a series of articles about right-wing pressure on Stanford, he quoted at length from the University replies. In one reply, he said, Sterling quoted what Rapoport called the University's policy on Communists on the faculty

: While membership in any lawful organization was not, itself, grounds for disciplinary action,

nonetheless a member of the Communist Party was "subject to a discipline that is inconsistent with professional integrity and competence, and with academic freedom and responsibility … and is, therefore, unfit to serve on the Stanford Faculty."

Baran told Rapoport that Sterling had called him to his office after the Cubberley speech. His main point was to ask me if I was a member of the Communist Party. I repeated to him that I wasn't. I had told him so before.

Baran had been proposed for a raise by his department, Rapoport says, but the administration had refused it. Baran says he has reason to believe that it was because of his statements on Cuba.

(Nick Baran is a sophomore in German. David Ransom is a freelance journalist and a member of Venceremos.)

University Embarrassed Having Baran on Faculty

By far the greatest embarrassment

suffered by the President's Office because of Marxist economics professor Paul Baran seems to have come after the Cuban Missile Crisis.

On October 24, 1962, during the crisis, Baran spoke on KPKA radio with graduate student Saul Landau and Professor Richard Brody of political science. Stanford Professor Condemns U. 5.,

headlined the Palo Alto Times. Its coverage unleashed what Morris M. Doyle, then chairman of the trustees, refers to in one of the copied documents made available recently as a continuing barrage of criticism concerning Baran.

In a letter marked Basic Reply

Lyle Nelson, director of University Relations, makes reference to academic freedom: Just as a free society has the obligation of respecting (a) man's right to speak, however unpopular his views may be, so a university must be hospitable to differing points of view.

But other replies emphasize the University's inability to fire Baran. In reply to criticism from a group of retired officers on the Peninsula, Doyle drafted what was apparently a form letter. Dr. Baran is a continuing embarrassment and source of irritation to the administration at Stanford and to the Board of Trustees,

he wrote. Although I do not personally see how an avowed Marxist can be an objective teacher of economic history, I am told that Baran is a fairly good teacher.

Consequently, because Baran had tenure, we must suffer him

until he proved incompetent or does something which would warrant termination &hellio; on other grounds.

Provost Frederick E. Terman used the same line of reasoning in another reply. Personally, I am largely in agreement with your views,

he wrote an angry attorney. Nonetheless, Your understanding of legal procedure and your thoughtful regard for the University enable you to appreciate our dilemma.

The evidence to prove that Professor Baran is engaged in unscholarly activities in the classroom is not sufficient for the administration or faculty to take punitive action. This is the critical point.

When UCLA held a series of four critiques of American foreign policy in early 1963, Baran was asked to speak. U.S. Foreign Policy Held 'International Threat,'

headlined the Los Angeles Times.

And angry complaint came from Southern California alum who quoted a speech given by J. Edgar Hoover to an American Legion convention to the effect that Stanford was providing the Communists' success in stimulating the interest and participation of some of America's young people.

I think Betty is a 'somebody,'

presidential assistant Fred Glover wrote Nelson. Will you please check and see how we should handle?

The reply was penned at the bottom of a list of her contributions to Stanford. Her brother was an ambassador in Latin America. Fine, substantial family.

When another Southern California alum wrote in February 1963 concerning a deluge of sincere criticism in Pasadena and L.A., Fred Glover replied that, Baran has tenure. To fire him, we would have to have a reason which would stand up in court. And we don't have any such reason. … I think we have just got to take the position that Baran is small potatoes in a great university.

The President's Office apparently wasn't the only one writing letters to distraught alums. Among the copied documents is a letter from a petroleum engineer calming an unhappy friend. Under his contract there was no legal reason or right to terminate this professor. If Professor Baran violates his contract, you may be sure he will be run off in record time.

"Fine letter," Glover wrote Sterling in a memo. One of the best letters on a sensitive situation that I've seen,

Sterling wrote him.

The embarrassment Baran was causing Stanford had apparently become somewhat financial. Why should I work for the success of the PACE program,

queried one alum, if there are men on the faculty that are working to destroy the religious, economic, and political beliefs I hold so dear?

A Superior Court judge wrote Sterling that PACE workers in Southern California were running into questions

about Baran and what was Stanford doing in regard to him and his like.

Some thought it would be helpful, he said, if they could tell their prospects … that Stanford is doing all that it can do to discourage him from remaining with the University.

The judge had earlier written Sterling concerning a friend's unwillingness to chat

about the unfortunate 'Baran affair'.

He quoted the man's reply to his query: I fear that any further donations could well be used to promote subversive teaching while such men are on the faculty.

I hope this does not mean that he has or is likely to change his Will.

The judge wrote, which as you know provides that something in the neighborhood of a million dollars will go to Stanford upon his death.

The President's Office apparently called up information concerning Baran's academic position—his salary, courses, the number of students who attended. Lists among the copied documents show Baran's Ec 120 (Comparative Economic Systems) to have been increasingly popular, attracting eighty-one students by autumn of 1962. Baran's salary was another matter. Receiving slightly under the department average in 1956/7, by 1963/4 he was being paid only $14,300—the least of any professor in economics. (High salary was $22,500.)

Sterling wrote the judge that he didn't think it wise to provide PACE workers with confidential personnel information. Should there be feedback to the faculty,

he said, I feel sure that I could be criticized.

Nonetheless, he said that the records showed that Baran is not reaching many students.

When the Chronicle reported on May 26, 1963, that Baran had been a party to forming the San Francisco Opposition,

a group it described as a new movement on the left,

Sterling reacted with pique. I wish that Professor Baran and Mr. Landua … would stick to their academic knitting,

he wrote an alum.

Baran died of a second heart attack on March 27, 1963. Even after his death, alumni complained bitterly of his association with Stanford. A memorial held by faculty friends a few days after his death was reported in the San Francisco News Call Bulletin. Since he has passed away the school has been relieved of an apparently difficult situation,

an alum wrote from Bakersfield. He should have been buried peacefully without the accompanying fanfare.

You may be right,

Glover wrote back, But it is difficult as a practical matter to tell a dead man's friends that they cannot mourn him as they see fit.

(Nick Baran is a sophomore in German. David Ransom is a freelance journalist and a member of Venceremos.)

Economist–Thinker Dies

, March 31, 1964, The Stanford Daily. Link

Memorial Resolution: Paul A. Baran,

by Melvin W. Reder, Lorie Tarshis, and Thomas C. Smith, Stanford Historical Society. Link

Stolen Documents Chart Baran Affair in 1960s,

by Larry Liebert, December 2, 1971, The Stanford Daily. Link

“Letters Expose Anti-Communist Policy,” December 2, 1971, by Nick Baran and David Ransom, Part 1 of 2, The Stanford Daily. Link

University Embarrased Having Baran on Faculty,

December 3, 1971, by Nick Baran and David Ransom, Part 2 of 2, The Stanford Daily. Link

Paul Alexander Baran, Wikipedia. Link

Paul Baran as Marxist Teacher,

by Prof Richard Wolff, Nov. 12, 2020, AskProfWolff, YouTube. Link