April Third Movement

Robb Crist

California Hippie Capers: 1968

Vic and I were in Palo Alto at the Free University Psychodrama Commune where residents were free to express every feeling and do what they wanted as long as they told the truth about it. Robb Crist swept into the living room while Vic and I shared a welcome-to-California smoke. Robb was surprisingly pleased to see us and asked if we could spare an hour to help him out. Vic and I were in California for adventure, so why not?

Vic and I were in Palo Alto at the Free University Psychodrama Commune where residents were free to express every feeling and do what they wanted as long as they told the truth about it. Robb Crist swept into the living room while Vic and I shared a welcome-to-California smoke. Robb was surprisingly pleased to see us and asked if we could spare an hour to help him out. Vic and I were in California for adventure, so why not?

Robb was a wild man, but you’d never know at first glance. He looked as straight and sober as a banker, although he was willing to join any revolution, ingest any pill, or try any experiment. He was also the disciplined driving force behind the 1000+ member Midpeninsula Free University

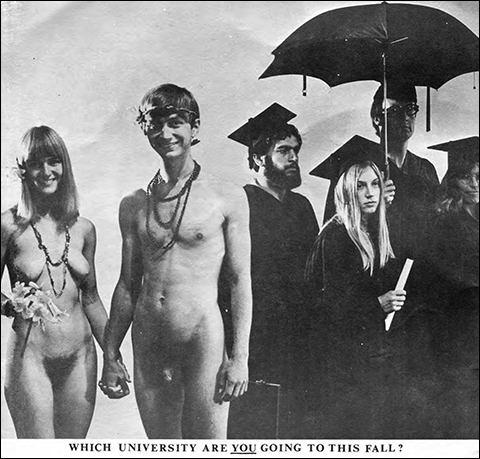

We drove into the foothills to a small cottage at the end of a verdant driveway. The cottage yard was a jungle of overgrown vegetation hanging with jingling wind chimes and floating prayer flags. Without knocking, Robb opened the door on a single large room with shabby furniture pressed against one wall and a white sheet hanging on another. A cloud of floral incense overpowered the pungent smell of eucalyptus trees. A photographer stood in front of the white sheet, messing with a professional camera and two floodlights. I followed Robb inside, clinging to Vic’s hand.

“Poke around and find something that fits,” Robb directed, pointing to a cardboard box of black graduation caps and gowns. Vic and I put the gowns on over our clothes, giggling over the combination of his bushy beard and graduation cap. “Perfect. You are the Berkeley couple,” Robb said.

“Find one that fits you,” Robb told his woman friend. He rummaged around in the box, put on a black gown, and looked in a mirror. “Great!” he said, “We are the Stanford couple.”

“Hey, Heather! Michael! Are you ready?” Robb shouted up the ladder to the loft.

“Yeah, we’re coming,” a man’s voice called down.

A young guy descended the ladder, grinning and slightly bashful. His girlfriend came after him. They wore only beads, flowers, and wide grins. “This,” Robb said with a flourish of his hand, “is the Free University couple.” No matter how this turned out, it was already worth the cost of our plane tickets.

When the photographer was satisfied with the geometry, he coached, “You from Berkeley and Stanford, look unhappy and gaze away from the camera. You are bummed out and bored.” He handed Robb, the “Stanford” guy, an umbrella and me, the “Berkeley” chick, a rolled up sheet of paper—my diploma. I struggled to keep a straight face. “You Free University folks, look directly at the camera and groove. Be cool. You are having a fantastic time breaking the rules.” Yes, they were. We all were. He took a series of photographs and sent us on our way.

A few weeks later, the Midpeninsula Free University catalog arrived offering exciting courses on yoga, auto mechanics, sexual healing, weaving, women’s liberation, meditation, and the Tarot. The photo taken the day we arrived was on the inside of the front cover.

I was sorry that Robb didn’t choose Vic and me to be the Free University couple, but Robb knew better. We were sightseers, window-shopping in this world. We were not gypsy-wild, stoned-out hippies crashing in the Haight. Underneath the beard and bells, we knew where we would sleep that night and that we would sleep only with each other. We had money to buy groceries at the food co-op, had been to the nude beach just once, and had plane tickets back home to Ithaca. Besides, Vic refused to wear flowers in his hair.

Our thanks to Elaine Mansfield for sharing the story of her encounter with Robb Crist. For more stories about her early relationships and other adventures, visit her blog at elainemansfield.com/blog.

The Midpeninsular Free University

Robb was a mystic. He was an intermittent graduate student at Stanford back in the 1950s, but the history he’s most remembered for surrounds the Midpeninsula Free University (MFU) and his role as its Executive Director. In November, 1968, he was interviewed by Pete Selby of The Stanford Daily, who reported:

Robb was a mystic. He was an intermittent graduate student at Stanford back in the 1950s, but the history he’s most remembered for surrounds the Midpeninsula Free University (MFU) and his role as its Executive Director. In November, 1968, he was interviewed by Pete Selby of The Stanford Daily, who reported:

The Midpeninsula Free University exists because it meets an educational need that the other educational institutions in the San Francisco area, Stanford for one, fail to recognize, according to Robb Crist, the executive director of the Free U.

And the only thing responsible for the Free U's existence is the people who participate in it,Christ stated.

To tell Robb’s history, we have to tell the history of the MFU. Jim Wolpman wrote a great article covering the MFU, Alive in the 60s: The Midpeninsula Free University. Here are excerpts from Jim’s article and from MFU newsletters:

Robb Crist is the most enigmatic (of the MFU leaders). Older, a perpetual graduate student, an intellectual gadfly, full of ideas, often a provocateur. He was around at the beginning and, as the MFU grew, seemed to pop up everywhere. Even later, after he had stepped back a bit, his positions on this or that were cited in meetings and discussions. Yet it’s not easy to say where he wanted to take the MFU, though one had the feeling that he knew and was enthusiastic about getting there. Some sense of Robb’s program can perhaps be gleaned from a plan he proposed in an early Newsletter. Utter transformation? Some kind of neo-Daoist politics? Hard to be sure, and that’s probably how he wanted it.

In describing Robb Crist, Jim referenced the Free University’s Summer, 1967 Newsletter where Robb presented his plans for upcoming programs. Those plans can be viewed here:

The Free University of the Midpeninula Newsletter, #3, Summer, 1967, p.4. Link.

Continuing with excerpts from Jim’s Alive in the 60s article:

MFU defining events

Five events—if you can call them that; they were more like unfolding sagas—stand out: (1) the quest for a Community Center; (2) Be-Ins and Liberation Festivals; (3) the Anti-War Movement at Stanford; (4) the Bombings; and (5) the ascendancy, if not domination, of the Marathon and the Psychodrama. Though they look to be separate and discrete, they're not. Not only did they occur almost simultaneously, but the attitudes and actions—as well as the re-actions—they engendered are inextricably intertwined.

Tensions Within and Without

Diverse as it was, several strands run through the entire ‘60’s counterculture. One was rejection of the stultifying conformity pressing in all round. America, at that point in its history, was seen as a vast technocracy with the university as a mass producer of men and women to place in its niches. This was the era of IBM, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, boring bankers, and

What’s Good for GM is Good for America.Freewheeling, free market capitalism, multi-millionaires in Levi’s, and flashy Wall Street traders were a long way off. Another strand was awareness that America, for all its pretensions, had sadly and unjustly repudiated and abandoned its poor and its minorities. Finally, there was the rejection of America’s Cold War mentality, which saw world events as having no intrinsic meaning other than their relevance to the Great Game with Russia.That was the common ground and, in the beginning, there was considerable agreement over what to do about it. But as the 60’s wore on and the counterculture became aware of itself as a potentially powerful force, latent tensions and conflicts emerged. Some indeed believed that the Age of Aquarius had arrived; others liked what was happening but realized that much needed to be done; still others were deeply troubled and found explanations and strategies in one or another political theory—anything from radical pacifism to militant Marxism.

All of which leads up to the question: Did the MFU have a position? Or was it just a hodgepodge of the entire counterculture?

The catalogs offer ample support for the hodgepodge view, and that’s what people on the outside looking in saw. But a careful reading of the documents reveals something different. In the beginning, a commitment to the emerging ideas of the New Left. Then an attempt to reconcile those ideas with its new-found dedication to the human potential movement. The result was that many in the MFU came to believe that out of the radical personal and interpersonal transformation experienced not only in encounter groups and psychodramas but also in Free U courses at large would come a new kind of politics. Open, more humane, more encompassing, and more creative. A politics that would, to paraphrase Bob Cullenbine, create a true community and a better society. Unlike the left, which saw its future in solidarity with the oppressed, the MFU wanted first to reach out and unify the counterculture; the rest would follow. Neither succeeded.

Tensions emerged, as I said, both within and without. Early on, one founding member claimed the Free University could never have a true politics.

The tensions that arose within the MFU over its response to being denied a community center and its reliance on psychodramatic politics have already been described. Similar tensions crop up, again and again, in The Free You.

Criticism from outsiders on the left came to a head in Fall 1969, with the publication of

What’s Wrong with the Free Universityin Palo Alto’s radical bi-weekly broadsheet, The Peninsula Observer. That article was reprinted in The Free You, along with responses from two Free You editors, a reply to one of those responses from the editor of The Observer, and a subplot involving copyright.In February 1970, the White Panthers—a local group of young radicals—conducted a sit-in at the MFU store and offices. Here’s a slightly facetious account, along with their demands and a description of their organization.

So, was the MFU revolutionary?

It did not have a systematic theory of capitalism, of class struggle, of history. It did not have a 5 or 10 or 12 point program. There was no party discipline, no formal cadre. It was not ready to take up arms. It did not believe that a dictatorship of the proletariat was a precondition to the day when one could

hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner… without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, shepherd or critic.Though I must say that the conclusion of the MFU’s Preamble bears some resemblance to Marx’s Utopia, but then all utopias do.What was revolutionary about the MFU was its belief that a fundamental change in societal relationships—a new, better politics—could only be achieved by radical individual and interpersonal transformation, that the human potential movement provided tools for such a transformation, and that the exact nature of that politics had begun to emerge and would continue to do so as the transformation fructified.

If the MFU has any claim to a small corner of history, it is because it served as a laboratory for that fascinating, failed experiment.

Besides—in spite of all the hassles—it was fun… and we learned a few things.

Robb believed in personal transformation, often using drugs such as LSD and nitrous oxide to achieve that transformation. He participated in Zen basketball, where, he explained in a Sports Illustrated article, You do not play to win. You play to get calm, to keep track of yourself, to keep your consciousness. It’s like taking acid.

Robb’s quest for enlightenment ended when he took a hot bath with a plastic bag over his head and a hose of nitrous oxide in the bag. By the time he was found, he had passed on. His friends commemorated his passing to the next level by emptying the tank of nitrous in his honor shortly thereafter.

A Brief History

“Alive in the 60s: The Midpeninsula Free University,” by Jim Wolpman, published online. Link

The Free University of the Midpeninula Newsletter, #3, Summer, 1967, p.4. Link

"California Hippie Capers: 1968,"by Elaine Mansfield, posted on Elaine Mansfield: Grief is a Sacred Journey. Link