April Third Movement

Phil Trounstine

Calbuzz, April, 2022

It is with heavy heart that we report the death of Calbuzz co-founder Phil Trounstine, who passed away peacefully at home on Monday afternoon. He was 72.

Phil for decades was a fiercely intelligent, hard-charging and widely-respected member of the California politics tribe — as the longtime Political Editor of the San Jose Mercury News, the onetime Communications Director for Gov. Gray Davis (Phil never tired of telling me that Gray was at 65 percent favorable when he left the governor’s office, well before the recall) and as founder and director of the San Jose State University Poll.

In 2009, he and I Iaunched Calbuzz and we had a blast for more than five years on the California campaign trail and state convention circuit, starting political food fights, committing more than a thousand acts of Actual Journalism and having too many laughs to count. As we often said, we were accountable to no one but each other.

We never put bylines on our stuff, because every piece we posted was a true collaboration, and in the years when we were cooking, before the health problems hit us, we’d talk to each other every day, dark newsroom humor-filled conversations, sometimes a dozen times a day or more.

Now it can be told: it was Phil who coined Calbuzz,

who dubbed Meg Whitman eMeg,

and labeled then-San Francisco Mayor Newsom Prince Gavin.

He devised our site’s singular absurdist art work, illustrating most of the 1,335 pieces we’ve posted in this space. He designed our finger-in-the-socket logo guy, morphed Jerry Brown into Gandalf and merged Obama’s Hope

poster with a rendering of Sigmund Freud to craft the image of our staff psychiatrist, Dr. P.J. Hackenflack.

As a reporter, Phil was the master of what we called the perceptual scoop

— grasping the big picture meta-angle of hiding-in-plain-sight trends or shifts in the political zeitgeist that no one else had yet recognized, explored or explained.

Years before soccer moms

became a thing in political reporting, for example, he understood and broke down for readers the critical importance of suburban women voters; outraged at the consequence-free lying of Whitman’s campaign for governor in 2010, he presciently railed against the death of truth

in politics; back in the ‘oughts, he forecast the collapse of the California Republican Party and offered a detailed prescription for how they could come back. Needless to say, the GOP foolishly ignored his advice.

Having started his own polling operation at SJ State, Phil was persnickety and proprietary about our polling stories, and would never let me near one. But his writing on the subject was serious, substantive and insightful, and he relished diving deep into the weeds about survey methodology, trashing the proliferation of media junk polls and demanding custom cross-tabs from PPIC’s Mark Baldassare, UC’s Mark Dicamillo or any other poll-taker he thought worthy of coverage in Calbuzz.

Phil also was the Calbuzz Social Director and delighted in planning the logistics, menus and sites of the Hacks and Flacks Dinners that became a regular feature of state conventions. His most spectacular success was the Calbuzz Hackenflack Dinner that highlighted Jerry Brown’s Inaugural week in 2011, drawing scores of insiders, electeds, lobbyists and other political hacks, including Governor Gandalf his own self.

His proudest achievement, however, was his marriage to Debbie and their wonderful, far-flung family, most of all their eight grandchildren, who appeared on his Facebook page even more frequently than his political observations or Wordle scores.

On Monday afternoon, according to family, Phil lay down for an afternoon nap, his beloved dog Bingo beside him, and…didn’t wake up. After all he’d suffered and endured in recent years, it was a blessedly peaceful passage.

E.B. White wrote that, It is not often that someone comes along who is a true friend and a good writer.

Phil was both, and I will treasure our partnership and our friendship forever.

RIP brother.

—Jerry Roberts

Sad news, Leslie. I have many fond memories of Phil, many shared at the Waverly Street house with Jeff and Doris Youdelman. I remember working with him on leaflets and posters at the Venceremos office on University Avenue in East Palo Alto. I remember the great fun we had co-writing Down at the Plaza,

to the tune of Billy Joe Royal's Down in the Boondocks

(lyrics available upon request). I remember him describing the impact of encounter group leader Hussain Chung (sp?) as like a bolt of lightning. And sadly, I also remember the cigarette perpetually hanging from his lip. We only saw each other occasionally after our Stanford years, but each meeting was filled with good memories, laughs, and sharp political discussion. I'll miss him a lot.

Let's not forget Phil's work prior to A3M, including his community organizing through the Midpeninsula Free University, contributions to the magazine and newspaper of the Midpeninsula Free University, his work as treasurer of that organization, and his great photography as an organizing tool. I remember Phil's work bringing political consciousness to the participants of the encounter groups which he was an avid participant of.

dies at age 72

Bay Area News Group, April 13, 2022; Updated April 14, 2022

When political strategist Garry South was preparing to help Gray Davis run for governor in 1998, his friend Phil Trounstine apparently was watching his every move.

South — chief of staff for then lieutenant governor Davis — was obligated by law to take time off the government payroll to work on Davis’ burgeoning gubernatorial campaign.

But South said he unwittingly continued to use his state discount on Southwest Airlines during his time off. That’s when former San Jose Mercury News political editor and commentator Trounstine — who passed away peacefully on Monday in his home in Aptos at age 72 — pounced. Despite their personal relationship, Trounstine had no qualms in asking South about his traveling

Phil called me and said, ‘I gotta ask you something, and I’m not trying to ding you here but you’ve been pretty consistently going off payroll, right?'

South recounted. I said ‘yes, I’ve been traveling more off payroll than on.’ And then he hit me with it: ‘Well, why are you traveling off the state payroll on the state discount rate?'

South knew in that moment he’d been treated to the Trounstine Special, a unique brand of unwavering journalism and confrontational style from a fierce, hard-hitting and widely-respected member of California political criticism who at that point had covered the state’s messy politics for over two decades.

All I could say was ‘Oh, sh–‘

South said. Soon enough the story came out and it was embarrassing to all of us.

It didn’t matter how close you were with him, how many family picnics you went on or whatever, if he found something he thought was a story he was going to pursue it and it didn’t matter if it was embarrassing,

South added. He was an incorruptible reporter. It’s a big loss.

Known for his incisive reporting and unapologetic criticism, Trounstine was a political animal respected and admired around Sacramento and the rest of the state for his deep devotion to journalism and fair political commentary

As the longtime political editor for the Mercury News for 20 years, onetime communications director for former governor Davis, founder and director of the San Jose State University Poll and co-founder of the California political commentary website Calbuzz, Trounstine was considered one of the top political reporters in California for decades. He dedicated his life to covering the politicians, scandals and power struggles of the nation’s biggest state — an accomplishment many current political leaders say will be sorely missed in today’s California.

California has lost a strong and clear political voice with the passing of Phil Trounstine,

said Congresswoman Zoe Lofgren. Phil was my neighbor and my friend, but never let that interfere with his obligation to be an objective reporter. He had good instincts, a sharp wit and believed in the power of journalism. My family offers comfort to his during this time of mourning.

Jerry Roberts, the other co-founder of Calbuzz, said in his obituary to Trounstine that as a reporter, Phil was a master of what he called the ‘perceptual scoop’ — grasping the big picture meta-angle of hiding-in-plain-sight trends or shifts in the political zeitgeist that no else had yet recognized, explored or explained.

Roberts said that it was Trounstine who years before soccer moms

became a thing in political reporting, understood and broke down for readers the critical importance of suburban women voters. He was outraged at the consequence-free lying of (Meg) Whitman’s campaign for governor in 2010,

and presciently railed against the ‘death of truth’ in politics.

Back in the ‘oughts, he forecast the collapse of the California Republican Party and offered a detailed prescription for how they could come back,

Roberts wrote. Needless to say, the GOP foolishly ignored his advice.

Carla Marinucci, former political writer for the San Francisco Chronicle, said in a Tweet that she was devastated

to learn of Trounstine’s passing, calling him a great political journalist

and a fearless reporter, a true scoop machine and mensch.

Honored to have worked together and competed for decades back to being student journalists at San Jose State University and the Spartan Daily,

Marinucci said. As MercNews political editor, Phil broke countless California and national stories (and)… made politicos sweat with their take-no-prisoners style. He’s no doubt up there pressuring God for a one-on-one. Go get ’em buddy.. we will miss you.

But Trounstine’s accomplishments go beyond journalism too. After Gray Davis’ successful campaign for governor in 1998, Trounstine stepped away from the newsroom to make the news instead of report it, serving as Davis’ communications director for about two years.

South said even as a staffer for Davis, Trounstine and the governor butted heads and had a relationship akin to that of a reporter and his subject, a dynamic that may have helped Davis in the end

Trounstine was also founder and — until April 2008 — director of the Survey and Policy Research Institute at San Jose State University, which produced the quarterly Calfiornia Consumer Confidence Survey. Trounstine also was co-publisher and co-editor of Calbuzz.com, one of the most popular websites for California political commentary.

I’d call Phil one of my most important mentors — and given Phil’s political bent, that mentorship sometimes came in the form of quotes from Chairman Mao,

said Bert Robinson, senior editor for the Bay Area News Group. I still remember how he urged me to expand my perspective in a career counseling session at the IHOP near his house in San Jose. ‘A frog at the bottom of a well thinks the sky is only as big as the top of the well,’ he said. Phil never restricted himself to the narrow view.

Trounstine is survived by his wife, Debbie Trounstine — a licensed marriage and family therapist — daughter, Jessica Trounstine — a professor of political science at UC Merced — son, David Trounstine and seven grandchildren. He also was step-father to Amy Vegter, Ryan Wilkes and Patrick Wilkes.

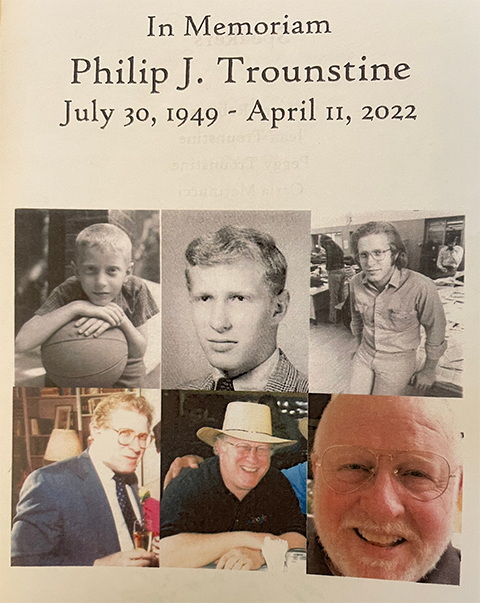

July 30, 1949 - April 11, 2022

Aptos, California - Phil Trounstine, an esteemed, insightful, and passionate California political journalist who found his greatest joy as the beloved patriarch of his family, passed away peacefully in his sleep on April 11, 2022. He was 72.

As a reporter, Phil was so determined and fearless he earned the nickname Mad Dog.

As a colleague and friend, he was frank and funny, with a vast store of kindness and generosity which he sometimes hid beneath a gruff exterior. As a husband, father, grandfather, brother and son he was devoted and doting, delighting in raucous conversations at dinner and elaborate family vacations. His life and work touched scores of people and he leaves behind a vast network of those whose lives were immeasurably improved for having known him.

Philip J. Trounstine III was born in Cincinnati, Ohio to Henry Philip Trounstine and Amy Joseph (May) Trounstine on July 30th, 1949. Phil grew up alongside his sisters, Jean Trounstine and Peggy (Trounstine) Breitbart, in a historic Jewish enclave of the city and attended North Avondale Elementary School and Walnut Hills High School. During childhood summers spent at Lake Charlevoix, Michigan, and Camp Kooch-i-ching, in Minnesota, Phil learned a deep love of nature and honed his competence as an outdoorsman. His time as a camper and as a counselor were pivotal to the development of Phil's skills as a leader and community builder, and led to many lifelong relationships. Phil was a mischievous, gregarious, and loyal friend who, from a young age, loved language and displayed enormous talent as a writer.

After high school, Phil attended the University of Vermont and Stanford University before earning a BA at San Jose State University. Amid the tumult of the 1960s and 70s, he worked tirelessly to help end the war in Vietnam, joining the radical anti-war group, Venceremos, and the Midpeninsula Free University

Phil received his degree in Journalism after serving as Editor in Chief for the Spartan Daily, the student newspaper at San Jose State. His ability and gifts as a journalist landed him the Eugene S. Pulliam Fellowship at the Indianapolis Star where he began his career as an investigative reporter.

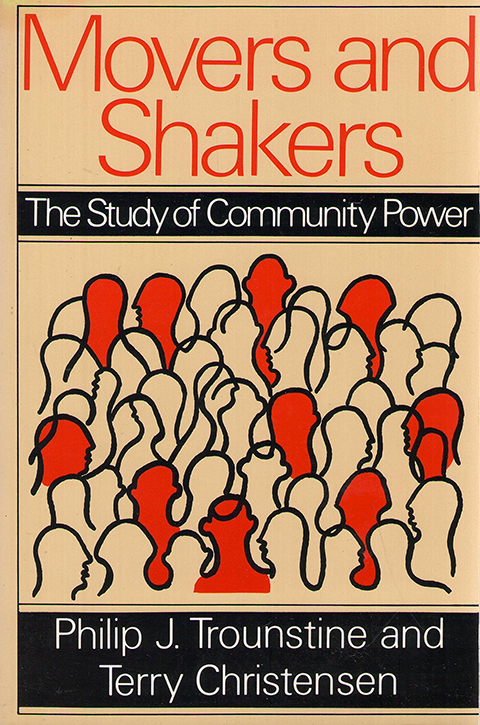

In 1978, Phil returned to California, accepting a position on the local desk at the San Jose Mercury News, a post that provided him inspiration and material for his co-authored book, Movers and Shakers: The Study of Community Power. He spent the next 20 years reporting for the Mercury News, moving up the ranks to become the paper's Political Editor, covering countless campaigns, from contests for City Hall offices to Governor, U.S. Senate, and numerous presidential races

Phil saw the work of journalism, and speaking truth to power, as crucial components to the maintenance of democracy. He loved to debate and challenge, and he had a wide and deep understanding of the political landscape. He also had a wicked sense of humor, which he wielded to prick the arrogance, pretension, and vanity of pompous politicians.

As he wrote biting political satire set to the music of show tunes for San Jose's annual Gridiron show, Phil was gaining a reputation, among the California press corps and beyond, as a smart, savvy and perceptive political analyst who, among other accomplishments, chronicled the growing influence, importance and reach of Silicon Valley.

In 1998, Phil put down his reporter's notebook to join the administration of Gray Davis, serving as Communications Director for the newly-elected California Governor. He resigned his post in 2003, to launch the Survey and Policy Research Institute at San Jose State University — and to dedicate more time to his favorite sport - golf.

Phil could not stay away from reporting for long, however, and in 2009 co-founded CalBuzz, a popular website that provided news, commentary and analysis of California politics

Family was of tremendous importance to Phil. His children, Jessica and David Trounstine, were born during the early years of his career. His first marriage was to Mary Catherine Luce and ended in 1989. Phil met the love of his life, Deborah (Debbie) Elaine Williams, two years later at a momentous party.

When they married on May 1, 1993, Phil and Debbie blended their families and Phil gained three more children, Amy (Wilkes) Vegter, Ryan Wilkes, and Patrick Wilkes. Phil and Debbie traveled widely around the world, pursuing their mutual love of culture, cuisine, and entertainment.

Phil's eight grandchildren Leah, Eliza, Elliott, Braeden, Sophia, Hugo, Henry, and Clara, were his utmost pride and joy

The loss of Phil Trounstine is profound

The following article appeared as the cover story in the April 29–May 5 issue of Metroactive.

INSIDE THE TECH MUSEUM of Innovation, a cadre of reporters and photographers jockey for space within a cordoned-off holding pen near the "Jet-Pack Chair" exhibit while they wait for Vice President Al Gore and Gov. Gray Davis to arrive.

INSIDE THE TECH MUSEUM of Innovation, a cadre of reporters and photographers jockey for space within a cordoned-off holding pen near the "Jet-Pack Chair" exhibit while they wait for Vice President Al Gore and Gov. Gray Davis to arrive.

As members of the state and national media show up, the pen starts getting crowded. Sight lines are scarce. The lighting is bad. The angles are wrong. A movie playing in the background makes hearing close to impossible.

This is the worst-planned event,

grumbles one photographer crouching beneath a television camera, that I have ever seen.

When Gore and Davis finally parade into the museum, they kneel among students from Horace Mann Elementary and assume their best wide-eyed, friendly-guy expressions. One problem: they both keep their backs to the cameras. The disappointment in the holding pen is palpable. How will the Chronicle, the Mercury, the Bee, the myriad television stations get their images for the 11 o'clock news and the morning editions? But then an intense stocky man with a blue suit and a regal shock of wavy graying hair briskly begins to take charge.

Ms. Magazine, they're coming here,

he says, directing a frustrated photographer from Ms. to kneel next to the Build Your Own Satellite

exhibit as Gore and Davis approach. As the entourage moves to the other side of the exhibit hall, he ushers another shooter out of the crowd and walks him right up to the vice president and the governor.

He's from the Merc,

he tells them, giving Merc photographer Dick Wisdom his imprimatur.

Although Gore and Davis ultimately do turn their faces to the cameras, the politicians keep their distance from the press maw. As they file out, the blue-suited handler hangs back, then walks right up to shake hands, whisper conspiratorially and introduce himself, as if he were the one running for office.

Phil Trounstine,

he says succinctly. Communications director for the governor; 20 years at the Mercury News.

ONE OF THE BEST political reporters in California,

Dan Schnur, former press secretary for Pete Wilson, says without hesitation, referring to Phil Trounstine's two decades as a reporter, editorial writer and political editor for the San Jose Mercury News. He was also one of the toughest.

But four months ago, Trounstine committed a sin unthinkable to many journalists. Within weeks of the last election, he jumped over the proverbial press barricades and left the Mercury News to take a job packaging the governor's image for consumption by the media and by voters in California and beyond. By becoming one of Gray Davis' closest aides, Trounstine jumped the sacred line that separates the people who report the news from the people who spin, massage and even try to create it. The governor's choice to recruit a senior political editor from a daily newspaper in one of the most prosperous and influential areas of the state was a significant event for Silicon Valley and for the state.

But no one, including Trounstine himself, has really known what to make of it.

Even the Mercury News, normally a stickler for disclosure and ethical hand-wringing, didn't evaluate the significance of the event in its own pages. The paper's only coverage was a minimal story tucked inside the front section with state news.

For Trounstine, it all began in December with a phone call from Davis campaign manager Garry South. Trounstine was enjoying a post-election break away from the office. He had been working in overdrive since the campaign began over a year ago, filing several stories a week in addition to writing frequent interpretive pieces for the Sunday "Perspective" section of the Mercury News. Now he was recharging and preparing, he says, to go full bore on a presidential campaign already gathering contenders: Al Gore, Bill Bradley, George Bush Jr., Elizabeth Dole, et al.

The last person he expected to hear from was Garry South. As Davis' campaign manager, South had been responsible for engineering a masterful campaign, defeating two self-financed Democratic contenders and a Republican who had his party's nomination sewn up from the beginning. During the campaign, South had been one of Trounstine's frequent sources. Now he was calling out of the blue, asking the political reporter to shed his mantle of journalistic objectivity and join the administration.

Trounstine was floored. I had never considered working for Gray Davis,

he says. It wasn't something that ever crossed my mind.

In considering the governor's offer, Trounstine realized that in order to give up his position at the Mercury, he would need to be more than a fringe player for the administration. He needed assurance from the Davis people that he would have a greater role in the administration than just writing press releases and doing advance work.

I wanted to know I was going to be on the inside,

he says, that I was going to be involved in the beginning of decision making rather than the end of decision making.

Days after the call from South, Trounstine met with Davis in the back seat of the governor's limousine to discuss the position in person. During a trip from San Jose International Airport to a fundraiser in Atherton, Gov. Davis explained why he wanted Trounstine to join his team.

Gov. Davis explained why he wanted Trounstine to join his team.

He said to me, 'I want to do good and I want people to perceive that I am doing good,'

Trounstine says.

The governor pushed some of the same high-minded moral buttons that had caused Trounstine to become a journalist more than two decades ago and had been guiding his judgment of politicians ever since.

I have always divided politicians into two camps,

Trounstine says. Those who want to do good and those who want to do well. Those who want to do well are seldom able to do good. I really believe this is a man who wants to do good.

So when the door to government cracked open, Trounstine flew in.

THE DOOR FROM JOURNALISM to government and back bears the scuff marks of many travelers in recent years, despite the discomfort it causes in journalistic circles. David Gergen left U.S. News and World Report to become a senior advisor to President Clinton. Bill Stall left the Associated Press to be Gov. Jerry Brown's press secretary. Both have since returned to journalism.

But that Trounstine was joining an administration he had just finished covering, presumably without fear or favor, rankled some of his colleagues.

The timing did bother me a bit,

confesses David Grey, a longtime acquaintance of Trounstine's and president of the Peninsula Press Club. It's like being an FCC commissioner and the next day working for one of the telecommunications companies.

San Francisco Examiner capitol reporter Robert Salladay was similarly surprised by the speed of Trounstine's transition. He reported observing Trounstine exchanging giddy high-fives

with a colleague after Gov. Davis' inaugural address.

I think what's troubling reporters is how quickly Phil became an advocate for the governor,

he says.

Trounstine's decision to leave journalism took even close friends by surprise.

I'm not surprised by a move, I am surprised by the move,

says Terry Christensen, who imagined Trounstine's ambition and workaholism might take him to the Washington Post or CNN or the L.A. Times, but not to government work.

What many observers don't know is it wasn't the first time Trounstine considered leaving journalism to take on the role of political handler. Almost a decade earlier, a similar opportunity presented itself to Trounstine in San Jose politics.

Soon after Susan Hammer took office as mayor of San Jose, Trounstine was one of at least three prominent local journalists in the running to become her press secretary. The other two were radio talk show host Kevin Pursglove and former local TV news anchor Jan Hutchins.

I do remember there was some level of discussion,

says Bob Brownstein, former mayoral budget chief. I'm not sure who was courting who.

Though Trounstine will only say he didn't confirm or deny anything at the time,

sources say he withdrew his name from consideration when he decided the position didn't have enough policy-making authority.

The main reason Susan Hammer never hired Phil is they weren't sure if he was applying for press secretary or co-mayor,

says Pursglove, who eventually landed the job.

THEN THERE'S THE FACT that the governorship of California, for all its headaches, is the best job in American politics. It's an executive post, as opposed to a legislative position, governing the seventh-largest economy in the world, with huge appointment powers and a private police force, unlimited access to media and no responsibility for foreign policy.

These words were written by Trounstine himself in 1996 in a story speculating on who the 1998 contenders for California's top post would be.

An examination of Trounstine's life and career reveals a fascination with the power of the office of governor and the dynamics of power itself. As a journalist he had a knack for divining the core of political influence, prying it open, and showing us what's inside.

Phil Trounstine describes his early family life growing up in Cincinnati as uneventful

and nuclear.

His father, Henry P. Trounstine, was the great-grandson of Captain Philip Trounstine of the 5th Ohio Cavalry, one of the very few Jewish officers in the Civil War. Trounstine's mother, Amy May Joseph, was a direct descendent of Isaac Mayer Wise, who founded the Reform Jewish movement in America. He attended a well-integrated public college-prep high school where virtually every graduate of the school went to college. The year Trounstine graduated, he says, four of his classmates went to Harvard and 11 to Yale.

Trounstine started college as an aspiring ski bum at the University of Vermont. His second year, he transferred to his father's alma mater, Stanford University.

By the time Phil Trounstine made it to Stanford, the campus was embroiled in protests against a war that many Americans had come to realize was deeply wrong. Blessed with deafness in one ear and a really high draft number (298), Trounstine didn't worry too much about the draft. He spent his time, he says, as a "dedicated participant against the war in Vietnam."

Trounstine dropped out of Stanford in 1970, perhaps the most tumultuous year in university history. It was the year the U.S. invaded Cambodia, when student demonstrators were killed on the Kent State campus and a bloody battle erupted between Stanford students and police at the university computer center.

Trounstine became involved with the Mid-Peninsula Free University, a counterculture institution put together by Vic Lovell and Bob Columbine. Lovell was Ken Kesey's roommate and both men had been influenced by the Merry Pranksters. The free university, which offered classes on topics ranging from community organizing to sand-casting candles at the beach, was launched on the premise that mainstream universities had been corrupted by the military-industrial complex.

They were brilliant grad students who believed there were courses that should be offered that weren't,

says Trounstine, who was influenced at the time by Marxist writer Herbert Marcuse, patron of the new left and author of Eros and Civilization and An Essay on Liberation.

Trounstine became involved in a psychodrama workshop,

where he and his classmates acted out real or imagined roles in their lives with other people playing other parts of their lives. It was an extraordinary growth experience for someone 19 years old.

At the time, Trounstine was more interested in photography and literature than in journalism, but he started to work for the university's Free You newspaper. In the fall of 1974, he enrolled at San Jose State University and threw himself into the Spartan Daily.

In the very first issue that fall, Phil Trounstine hit the front page, a position his byline dominated for the rest of the term. While other members of the staff delved into the new trend of topless sunbathing, Trounstine pursued stories that invariably took him straight to university president John H. Bunzel's office door.

His first story, Sept. 10, 1974, probed a brewing labor dispute between the economics professors and the university that erupted in a rash of faculty departures later that year. The professors were Marxist economists whose opinions were, in effect, being stomped out. This seemed to have an effect on Trounstine. He followed their plight, even reporting later in the term on which of the departed professors had been able to find other teaching jobs.

Trounstine's first editorial was published Sept. 12, 1974. The war resisters were and are men of principled conviction,

he argued, while Nixon is a man of pious criminality.

Later in the term, he vented his frustration at Bunzel in an editorial for not speaking to the press—namely Trounstine.

The following term, Trounstine took over as editor of the paper. On his staff were future Chronicle political reporter Carla Marinucci and a future executive editor of the Mercury, David Yarnold.

Trounstine's transition from counterculture and student journalist to mainstream daily reporter was quick and seamless.

I don't think his background ever left him,

Grey says. He just kept it in check.

After college, he took a reporting job at the conservative Indianapolis Star

, where Trounstine began an analytical study of the individuals who hold power in the community. He conducted the first of three "power studies" in Indianapolis and found that 29 of the 32 most powerful people came from the business-sector elite. Soon after he came back to San Jose to work for the Mercury News, he conducted another study and found San Jose's power structure more like that of a typical sunbelt city, with power more evenly split between public- and private-sector leaders. It evolved into a book Trounstine wrote with Terry Christensen, Movers and Shakers: The Study of Community Power.

Trounstine began working as a City Hall reporter in San Jose in 1978, where he came to be known as a tough, tenacious reporter. They called him 'Mad Dog,'

Christensen says, because he just wouldn't let go. You'd have to be pretty effective to change his mind.

If Trounstine took some satisfaction in striking fear in the hearts of the powerful, he couldn't show it in his work. But if any of them took themselves too seriously, they could find themselves lampooned onstage at the Gridiron Roast. Trounstine founded the Gridiron Roast, with some other reporters from the Mercury News, and for years put on the annual show to skewer local politicians in the name of raising money for charity.

They would get all the politicians there; it would always sell out,

Grey remembers. People knew Phil Trounstine wherever he went. He always had a little ham in him; he was a talented songwriter and wrote lyrics to a lot of things.

In 1983 Trounstine was promoted to the editorial board, a group of Mercury News staffers from around the paper who met weekly to discuss positions on issues the editorial page might take. It was then that he began to solidify his reputation as San Jose political kingmaker and began to consolidate his own fiefdom at the Mercury News. In 1986, Trounstine was appointed political editor, a position that seemed to be created for him.

I was used to being a free agent,

Trounstine says. I'd gotten to the point in my career when I could do what I wanted to do, cover what I wanted to cover.

A colleague sums it up differently:

Phil didn't have any editors. He had a degree of autonomy that was the envy of everyone in the universe.

FOR ALL THE BYLINES and spirited editorial board discussions, Trounstine had reached the pinnacle of his influence at the Mercury News. But that's not why he left.

I had a great job at the Merc, that is true,

he says. But I felt like I had a great opportunity. Those chances only come along once in your life.

And Trounstine was becoming familiar with the unexpected turns and detours life can bring. In 1989 he weathered a painful divorce from his wife of 14 years, who began to live as a lesbian. His father suffered from heart problems, and while Trounstine was visiting him, he suffered a heart attack himself. When his father died in 1997, Trounstine wrote his obituary for the Cincinnati Enquirer.

In the end, Trounstine says, the decision came down to how best to make a contribution to society. "This was an opportunity to be on the inside and be involved in creation of message, of policy, of direction; to be a participant in the state that I love," he says. I felt I was making a contribution, but this was a chance to paint on a larger canvas and in a different way.

As a reporter, Trounstine had a reputation for keeping his copy scrupulously fair regardless of his own beliefs.

Whatever my personal views were, I attempted to maintain impartiality,

he says.

Yet during the 1998 election, a new tenor of truth seemed to emerge in Trounstine's work. And at least part of that truth, for Trounstine, was that Gray Davis was the best choice for governor.

In an early profile of Al Checchi--one that Trounstine's friends say he was very proud of--published in October 1997, Trounstine quoted Checchi as saying he was prepared to spend "whatever it takes" of his personal fortune to win the race. Trounstine repeatedly resurrected that quote--"whatever it takes"--to make the point that Checchi was a rich guy trying to buy the governor's office.

Checchi, meanwhile, was running for governor on his reputation as the shrewd financial manager who took a sagging airline and restored it to profitability. Trounstine's story revealed that the Checchi legacy at Northwest Airlines was far more complex than his campaign's fairy-tale storyline.

The story quoted sources who blamed Checchi for saddling the airline with debt defending itself against his leveraged buyout, and then asking the state of Minnesota and the airline employees to bail him out with subsidies and pay cuts.

Checchi's reaction to the story was something Trounstine had seen before—in his days railing against Nixon and SJSU president Bunzel. Against the better judgment of campaign manager Darry Sragow, Checchi cut Trounstine off completely from access to the campaign.

But Checchi couldn't avoid seeing Trounstine again during his meeting with the editorial board of the Mercury News. And Trounstine didn't hesitate to reveal further Checchi shortcomings.

When publisher Jay Harris asked Checchi how he intended to pay for some of his programs should the economy grow at the rate of inflation, Checchi refused to answer the question in a particularly arrogant way. I'm not going to accept a hypothetical that I don't believe is in the realm of the possible,

he said.

[Trounstine] reported the attitude as well as the news that he wouldn't answer the question,

observes Kam Kuwata, campaign manager for Jane Harman. It certainly had an impact in shedding light on who is this guy spending all this money.

Trounstine added that when Checchi was asked whom he'd consulted with on South Bay issues, he pronounced the name of a former mayor as Tom MacInry.

But possibly the most scathing description Trounstine used of Checchi was constantly referring to him on first reference not as businessman

or multimillionaire

but as airline tycoon.

By contrast, Jane Harman earned no such label even though she spent millions of her own money on her campaign, especially for television advertising.

In the end, the campaign was a two-horse race between Gray Davis and Dan Lungren. And Trounstine stepped up to write a piece that reintroduced the South Bay to Dan Lungren.

In a six-page piece that appeared Sept. 27 in the Merc's West

Sunday supplement, Trounstine didn't waste any time in hanging Nixon around Lungren's neck. In his lead, he set the scene of 1968, a year when Trounstine was deeply involved in the counterculture and Lungren, readers learned, was a student at Notre Dame leading campus forces for the former vice president who'd vowed we wouldn't have him to kick around anymore: Richard M. Nixon.

That Lungren's experience during those years could differ so drastically from his own struck Trounstine as one of the most important facts to convey to readers as he was interviewing the candidate on a bus between campaign stops.

Dan Lungren and I were very close in age,

Trounstine says. It struck me that to be for Nixon when he was in college was an incredible insight into who he was. No one had made the point about who he was, in his bones.

Lungren kept trying to steer the conversation to Ronald Reagan. Ultimately Trounstine allowed him to, but the writer noted in the story that a discussion of Nixon was not where Lungren wants this converstaion about him to go.

The essential question Trounstine framed: Is Lungren too conservative for California?

I believe I was fair and balanced to everyone in the campaign," Trounstine says. "My goal as a journalist was to be fair and to be tough.

Trounstine was tough on Lungren, as were a lot of reporters in the state, says Lungren media consultant Rick Davis, who concedes the piece didn't exactly help Lungren among moderate Republicans in Silicon Valley. In terms of the Nixon stuff,

he says, it was part of Dan Lungren growing up. It wasn't something that formulated any kind of political philosophy. Dan is a very different personality from Nixon.

ENSCONCED IN GOV. DAVIS' inner sanctum, Trounstine now rarely speaks to his former colleagues, instead helping shape the governor's message from within. Press calls go to the governor's spokesman, Michael Bustamante.

Nevertheless, the Sacramento press corps who knows him can see Trounstine's fingerprints all over the new governor's administration.

Phil appears to be very involved,

says Salladay of the Examiner. He was a fanatic reporter. Now he's being a fanatic spokesman for Gray Davis.

The Davis administration's relationship with the press got a horrific start in February when the governor barred top officials from speaking to the press. Trounstine explained the gag order,

as it was called by the Associated Press, as necessary because Davis did not want people who don't understand his positions on critical issues to be freelancing their views.

There have been other blunders.

Early on, he decided some old hands in the state Senate were obstructing Davis' education bills and decided to try to pressure them in the press. He targeted senators John Vasconcellos of San Jose and Tom Hayden of Los Angeles, both old-guard liberals who sit on the Senate Education Committee and who were picking apart the bills sentence by sentence. Trounstine called his old bosses at the Mercury to try to use his influence to plant an editorial there seeking support for Davis' legislation. Bustamante did the same at the San Diego Union-Tribune, and Davis education secretary Gary Hart called the L.A. Times.

The ploy backfired. Vasconcellos told the Chronicle he erupted like the best volcano

when he heard Trounstine had called his hometown paper behind his back. The Mercury didn't run an editorial, and Trounstine ended up earning the mistrust of a man who's been a California legislator since 1966.

It was a bonehead, amateur move,

says one Capitol reporter. It's the kind of move somebody makes when they haven't been here very long.

The governor also has been chided for an overkill of spin. One of Trounstine's latest manufactured news events was the governor's vaunted celebration of his first 100 days in office. When reporters arrived at the Capitol's press room, they encountered a brand-new backdrop replacing the standard royal blue with floor-to-ceiling peach and baby blue banners with the words new directions

and lasting values

framing an artist's rendition of the Capitol.

Reporters were given bound booklets embossed with the governor's seal: Governor Gray Davis: The First 100 Days.

Sacramento Bee columnist John Jacobs withered the dog and pony show: We're not talking accomplishments here but—and this is perfect for the postmodern politics of the late 1990s--the appearance of accomplishments.

Another Sacramento Bee columnist, the reliably grouchy Dan Walters, says the 100 days thing has never been done by a governor before.

It's something they completely dreamed up on their own to create publicity for themselves,

Walter says. It was kind of a failure. No one mentioned the 100 days except the pundits.

At least, Walters says, Trounstine can take credit for ending the trumpet fanfares that used to follow the governor when he appeared at public events.

TWO YEARS BEFORE THE 1998 California gubernatorial campaign, Trounstine wrote the words that would ultimately become Gray Davis' calling card. It was actually a story dismissing Gray Davis' chances of becoming governor should both he and Dianne Feinstein decide to run. Nevertheless, he referred to Davis, who was then lieutenant governor, as perhaps the best trained governor-in-waiting California has ever produced.

Trounstine took a good bit of ribbing for the quote, especially after he crossed over to work for Davis.

But Trounstine found a way to make light of the quote in a speech Davis gave to an assembly of newspaper editors in San Francisco, including editors from the Mercury News. Perhaps?

Davis joked. I mean, how many offices do I have to hold? Do I have to run for the mosquito abatement board?

The governor, famous for appearing rehearsed and wooden, is the kind of guy who shows up at a summer barbecue in a gray suit. But since Trounstine began writing his speeches, it would appear Davis has developed a self-deprecating sense of humor.

In the same speech to the publishers, Davis used humor to defuse criticism that he tries to make decisions on everything from the font size in documents to the tire pressure in Caltrans vehicles.

I want to first respond to a criticism that appeared in many of your papers that I am too much of a micro-manager,

he said. Now that is simply not true. I want to categorically deny it. However, if some of you don't yet have your press pass, I'll be working the lamination machine outside when this is over.

The administration has shaken off the frost that came with the gag order by giving Capitol reporters prompt access to information.

I personally have not had a problem with getting access to state officials," Salladay says. "Just this morning I got resources secretary Mary Nichols on the phone in 20 minutes.

Some observers have noted a certain press-savviness in the way Gov. Davis operates, characteristic of a deadline-oriented reporter working behind the scenes.

Early this year, when Richmond High basketball coach Ken Carter locked his players out of the gym until they brought their grades up, he was lauded throughout the state as a hero. On the players' first game back, television crews were there to cover the story. The newly elected governor made a dramatic appearance at the game, a symbol of his commitment to education just in time for the evening news.

That Davis was there reflected the way a reporter would think about the story,

Schnur observes. One of the most important qualities for a press secretary is learning how to think like the press corps that's covering you, and that's obviously something Phil can do in spades.

Another quality is willingness to deflect credit to the boss.

It was the governor's idea,

Trounstine says. He just wanted to go. My communications operation made it happen.

He just wanted to go.

This is the same governor who, before Trounstine, showed the sports and media sense to call an impromptu press conference with 34 seconds left in the fourth quarter of the 49ers-Green Bay Packers game in December. While Davis droned on, reporters stole away to watch Terrell Owens make The Catch II.

Trounstine can point to a number of perception coups scored by Davis in his first few months in office. First and foremost, Davis has been unwavering in his message: education, education, education. Second, a number of Davis initiatives have gotten incredibly good press.

On his trip to Mexico, for example, news stories consistently lauded the trip and compared Davis favorably to Pete Wilson, whom the press blamed for souring California's relationship with Mexico in the first place.

We were not out there spinning the contrast,

Trounstine says. "We didn't have to."

When he speaks of the performance of his new boss, Trounstine uses words like staggering,

moving

and exciting.

He says the governor made it clear to him he wanted to do the kind of things I would feel good being a part of.

In the coming years of the Davis administration, Trounstine will be asked to package more and more elaborate news events to tout the governor's achievements, to make him personable, even likable. It won't be an easy task.

I'm working harder now than I've ever worked in my life,

he says.

And politicians have a way of disappointing idealists. Should the governor disappoint Phil Trounstine, he hasn't ruled out a return to the Fourth Estate

I suppose if I decided that there was a great opportunity and I got tired of working on the inside that I might do it again,

he says. And wouldn't, say, editor of the Mercury News be great?

It's not something I've thought about seriously,

he says. I'm not sure I'll ever go back to journalism.

Phil Trounstine: 1949–2022,

by Jerry Roberts, Calbuzz, April, 2022. Link

Phil Trounstine, former Mercury News political editor and Calbuzz.com co-founder, dies at age 72,

by Aldo Toledo, The Mercury News, Bay Area News Group, April 13 & 14, 2022. Link

Philip Trounstine Obituary,

The Sacramento Bee, April 23 & 24, 2022, Legacy.com.Link

The Changeling,

by Michael Learmonth, Metroactive, April 29–May 5, 1999. Link

Movers and Shakers: The Study of Community Power, by Philip J. Trounstine and Terry Christensen, St. Martin’s Press, 1982.