April Third Movement

David F. Pugh

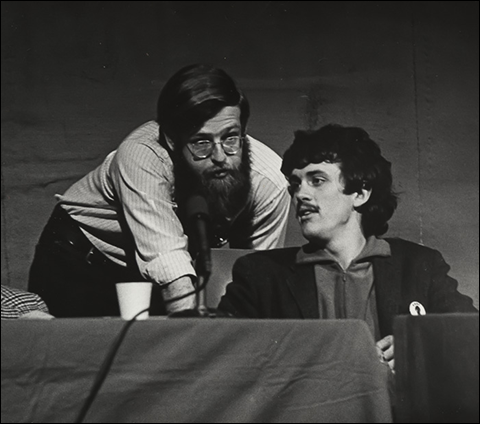

held in Memorial Auditorium at Stanford on March 11, 1969

The Activist

David Pugh—teacher, lawyer, historian and political activist—died on January 26, 2023,

aged 74

David Pugh – teacher, lawyer, historian and political activist – died on January 26, 2023, aged 74 Twenty-nine Stanford students barged into a business meeting of the Stanford University Board of Trustees. The students wielded a list of demands aimed at ending military research on campus and at the Stanford Research Institute. The Trustees refused to listen. Furniture was broken. The campus police were called in. The administration called it a break-in. The students called it an “opening-up.”

The twenty-nine students were suspended from classes. Several months later, they were allowed to return if they paid a fine for the damage. Instead of paying anything to the university, they paid the fine to the Black Panthers.

Among these students was David Pugh. A month later, at a meeting of 1,500 students and faculty to discuss the university’s ties to the Vietnam War, David spoke from the floor in support of the demands of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). “Don’t listen to Pugh,” a professor said, “He’s majoring in the SDS.” The year was 1969.

Stanford and Vietnam launched David as a 60s/70s activist but he was much more — a caring father and teacher, a passionate humanist, a champion of the less fortunate and a friend to many.

David Pugh grew up in the comfortable towns of Larchmont and Rye on Long Island Sound. A self-termed “rebel” in elementary school and at home, the watershed of his youth was having Al Cullum as his 5th grade teacher.

David wasn’t bored in Mr. Cullum’s class, and he didn’t act out. There was fairness. Mr. Cullum reserved the right to throw an eraser or a piece of chalk over the head of a student goofing off in class. If it hit the student by mistake, the student had the right to throw it back at the teacher. While David had been frequently sent to the principal’s office in grades 3 and 4, Mr. Cullum never sent him there. As a bonus, Mr. Cullum organized an after-school pavement hockey league in which David played.

Every class activity was set up to be fun. There was an Arithmetic Olympics, a Geography Race (with teams), and more. Each week there was a Vocabulary League competition that used words the students encountered in books and poems. David long remembered the words “sepulchre” and “tintinnabulation” from poems by Edgar Allen Poe. Later in the week, Mr. Cullum brought in a reproduction of a painting by maybe Paul Klee or Vincent van Gogh. The students tried to guess the name of the painting, and then discussed its qualities. That night’s assignment was to research and write a page about the crazy man who cut off his ear. The class play was Saint Joan, in which David played the role of the executioner.

Mr. Cullum recognized David’s intelligence and energy. David never forgot his enthusiasm for learning that year. The outside world of adults, books, plays and art was no longer out of reach. He stayed in touch with his 5th grade teacher for decades.

David was a natural athlete. He played competition tennis on the Eastern junior circuit and played four varsity sports at Phillips Exeter Academy: soccer, winter track, tennis and lacrosse. He played tennis his 10th-grade year. The next spring, he switched to lacrosse because his friends were on the team.

He was also a natural in the classroom at Exeter. He enjoyed the discussions and debates around the oval Harkness tables. He had ample outlets for his writing skills. He won prizes in Latin and Religion. He was a National Merit Scholar, and graduated Cum Laude. He scored a 5 in five different AP exams, which allowed him to enter Stanford University with sophomore status. He selected Stanford for the adventure of seeing a different part of the country.

There were two pivotal books in David’s early political development. At Exeter, he read The Autobiography of Malcolm X soon after Malcolm X’s assassination. For the first time he got a picture of the oppressive conditions in poor, African-American communities. The second book was The Two Vietnams by Bernard Fall. He was given the book by an Australian medic who had worked in Vietnam with the Red Cross. This was in the summer after David’s first year at Stanford. He was in Hong Kong teaching English in the Volunteers in Asia program. Reading Fall’s book, he came to understand that there was a civil war in Vietnam, and that the U.S. government was supporting a repressive dictatorship. He also came back to the United States outraged at the huge gap in living standards between the rich and the poor in Hong Kong.

The day David returned to Stanford, he walked up to the SDS recruiting table and joined the group. In doing so he joined the gathering vortex of the anti-war, feminist, and Black Power movements in the Bay Area.

David was arrested twice during his SDS days. The first time was when Stanford students joined a blockade of the Oakland Induction Center. The second time was when hundreds of students surrounded and shut down the Stanford Research Institute.

David left Stanford, three credits shy of a diploma, for a larger stage. He felt that struggle in the university was limited. He wanted to be part of the revolutionary struggle of the working class. He moved to San Francisco and worked in a series of blue-collar jobs among Mexican, Chicano, Black and Filipino workers. In the plants where he worked, he struggled against the management and the sell-out and do-nothing union leaders. Where there wasn’t a union, he tried to organize one.

For seven months he installed phone equipment for Western Electric. He was the union steward on his floor. He testified at a public rate hearing that his employer was overcharging its customers and underpaying its employees. Several days later, he was fired.

When the SDS splintered, David joined the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP). The RCP took its line from Mao and the lessons of the Chinese revolution. In the mid-1970s, the RCP leadership asked him to move to Chicago. He became the editor of the party newspaper The Revolutionary Worker and wrote many party pamphlets. To anyone who would listen, he explained that a working-class revolution in the United States was imminent, and that the RCP was in the perfect position to lead it. Decades later, looking back, David described the Chicago years as working in a “bubble”. The members of the RCP lived within their own echo chamber.

In the early 1980s David resigned from the RCP. He fell victim to a depression which would return periodically. He moved to New York City and thought about how to restructure his work life and raise his two daughters. In his apartment in Washington Heights, he helped to organize a rent strike to force the landlord to make necessary repairs.

David went back to school. At Hunter College he received the three credits he needed for a Stanford A.B. Then he attended law school at the City University of New York. He felt that becoming a public interest or civil rights lawyer would be an effective way to fight for political and social change. While he attended Hunter and CUNY, he worked as an urban park ranger. Central Park was his favorite venue. He came to know and appreciate its wildlife. He advocated for the bike lanes we still see in the park in the interest of pedestrian safety.

For five years he practiced at the NYC Commission on Human Rights. Most of his caseload were gender discrimination and sexual harassment cases. For two years he worked at a small law firm in Newark, litigating employment discrimination cases. Eventually he became disenchanted with the adversarial nature of the legal process. He turned to teaching, intending to channel the qualities of Mr. Cullum.

David’s first teaching job was at Rikers Island. His classes were mainly to prepare youth in prisons for a high school equivalency diploma (GED).

For the next decade he taught at a series of racially and economically segregated high schools and middle schools in the Bronx and Harlem. He taught American history, government, economics, law, and global history. During a five-year sojourn to his beloved Bay Area, he taught social studies at a charter high school in Oakland. He loved the work.

At one of the schools in the Bronx, a group of students in his law class asked if they could use the class to organize a walk-out to protest a shooting in the neighborhood. David agreed. His job was to step back and let his students take the stage and exercise their power. Two-thirds of the school’s student body participated in the walk-out.

His efforts to politicize other faculty members often irritated the administrators. He was typically moved to a new school each year. One administrator tried to take away his teaching license. He narrowly retained it – upon appeal – without any support from the teachers’ union.

David continued to be interested in international affairs and radical causes. He participated in fact-finding missions to the Philippines and India. In the Philippines he researched magsasaka grievances which fed a Maoist insurgency. He was interviewed on Manila television. In India he documented the plight of poor farmers being displaced from their villages by mining firms and a proposed automotive plant.

David increasingly thought of himself as an historian. He went back to school, and received a Master’s in History from City College of New York.

His teaching career took a new tack. He taught English as a second language (ESOL) to recent immigrants. He also taught adults in Harlem to prepare for the GED. These students ranged from 20 to 70 years of age. Classes were small, consisting of a dozen students. David concentrated on their writing, encouraging them to use their life experiences as subject matter. One of his annual assignments was to ask his students to write an essay on why they dropped out of high school. The responses included uncaring high school teachers, family turmoil, poverty, unsafe schools, unplanned pregnancy, and getting stuck in dead-end special education programs. David’s goal was always to help improve their lives.

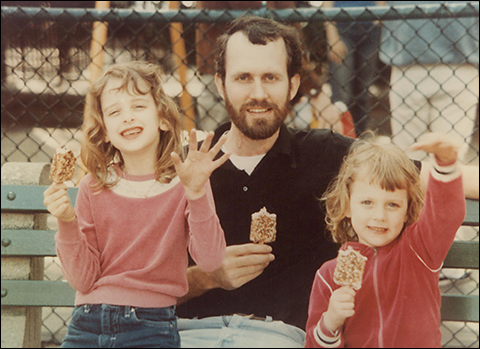

Having daughters really changed David. It gave his life a purpose outside of politics. He tried to give Jackie and Dina the emotional support he felt was lacking in his own childhood. He regularly bragged about his girls. In his annual holiday letters to family members, he shared their elementary school and junior high essays, poems and artwork. When his daughters became parents, he enthusiastically kept in touch with the exploits of his four grandchildren.

Over the decades David maintained his networks of Rye, Exeter, Stanford and radical friends. He enjoyed reunions with school classmates. He joined a gathering of former 5th graders who contributed to the film A Touch of Greatness, a PBS documentary about the life of Al Cullum.

In his later years he explored new parts of the world on Road Scholar trips. The trips usually had a hiking component. Cape Breton Island, Ireland, British Columbia, and Yosemite were some of the destinations.

David loved loud, brash and progressive music. He understood that music can speak to the hearts and minds of people. The more explicitly revolutionary the lyrics, the better. His musical tastes ran from Bruce Springsteen, The Clash, Afrika Bambaataa, and Grandmaster Flash, to The Chicks, Steve Earle, Joe Ely, Drive-By Truckers, and more. If the lyrics had a working-class edge, took stands against police brutality, were feminist, or tackled racism, he was sure to like the music.

David always had music on in the house. It filled him with joy. Attending a Drive-By Truckers concert in Brooklyn, he reveled in the wall of sound.

David felt that it was his duty to help the poor and the oppressed. Being a white man of privilege with an elite education, David recognized that he could, at least, act as a buffer to keep those with authority from taking advantage of the powerless. He often strove for more. As an organizer and an educator, he worked tirelessly to help workers and minorities understand their situation and to fight for their freedom.

David’s final writing project was a book about the Vietnam War. He was afraid that there were stories which would be lost if he did not bring them together. The book covers four streams of opposition to U.S. involvement in Vietnam: GI opposition, veteran opposition, civilian opposition, and the revolutionary movements of the Vietnamese people. The manuscript is 500 pages long. It is looking for an editor and a publisher.

There was often a gleam in David’s eyes. Some women called him sweet. Men sometimes called him arrogant. Many people saw in him a fun-loving troublemaker. David was always looking at the horizon, a better world in his sights.

David was pre-deceased by his brother Edmund W. Pugh III. In addition to his brother James R. Pugh and sister Elizabeth L. Pugh, he is survived by his daughters Jacqueline Sackler and Dina Pugh, four grandchildren, a niece and two nephews.

The Activist: David Pugh—teacher, lawyer, historian and political activist—died on January 26, 2023,

by Dina Pugh, Ever Loved. Link

aged 74,

Interview with David Pugh conducted by Vanessa Ochavillo, 2018. The Movement Oral History Project (SC1432). Department of Special Collections & University Archives, Stanford Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Link

Trustee Forum, Stanford University, A3M Historical Archive, March 11, 1969. Link