April Third Movement

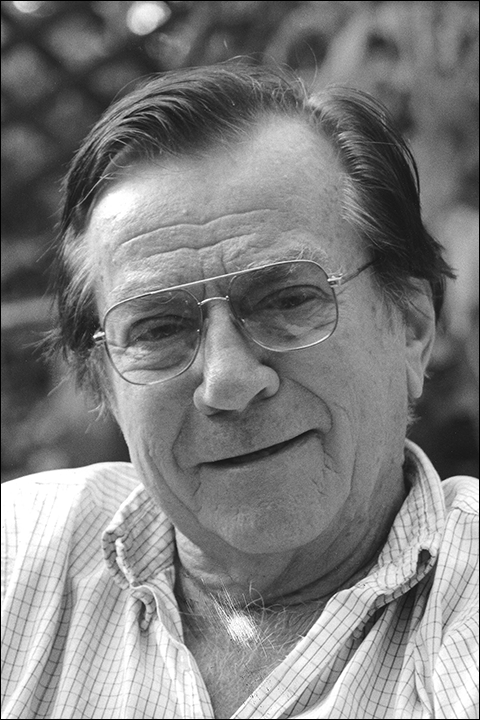

Charles Drekmeier

(Photo credit: Courtesy of the family)

Charles Drekmeier, Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Stanford University, died at home in Palo Alto on August 25, 2020, just shy of his 93rd birthday. Known for his creativity, intellectual curiosity, and liberal politics, he was adored by his students, many of whom went on to distinguished careers in politics, law, academia and the nonprofit sector.

Born in Beloit, Wisconsin to Albert and Marion Drekmeier, Charles earned degrees from the University of Wisconsin (BA), Columbia University (MA) and Harvard University (PhD). Interspersed with his studies, he was drafted into the army near the end of World War II, interned for the State Department to study the effects of the European Recovery Program (Marshall Plan), and received a Fulbright Scholarship to study the history of law and politics in India, where he lived for a year while compiling notes for what eventually became his PhD thesis, published as “Kingship and Community in Early India.”

While at Harvard, Charles met his wife-to-be, Margot Loungway. Shortly after marrying in 1958, they moved to Palo Alto to join the Stanford faculty—Charles in the Political Science and Sociology Departments, and Margot in the History Department.

A social theorist, Charles was fascinated by the origin, evolution and history of ideas. His interdisciplinary approach to education earned him the admiration and respect of his students. As adults, his children recall hearing from numerous former students that Charles and Margot were their favorite teachers at Stanford.

Charles and Margot were deeply engaged in the Civil Rights and Anti-War Movements. They sponsored courses in Peace Studies, and in 1965, Charles co-founded the Stanford Committee on Peace in Vietnam, which sponsored a 24-hour campus teach-in (the second in the nation). His liberal politics and fierce independence at times put him at odds with the more conservative Stanford administration

For 23 years, Charles and Margot co-led an honors seminar (meeting at their home) called Social Thought and Institutions. The program focused on a single topic, such as “community” or “utopia,” for an entire academic year. Right up until his death, Charles was participating in Zoom gatherings with former students from the 1966/67 seminar focused on “Myth and Symbol.”

In 1969, with three children under five in tow, the Drekmeiers participated in the Stanford Overseas Program, spending an academic quarter in England and another in Vienna. That summer they took advantage of the opportunity to explore Europe in their VW camper van.

After 40 years teaching at Stanford, Charles retired in 1998, and was able to relax and enjoy his senior years. He loved classical music (he played flute in the Peninsula Symphonic Band), reading, art, enjoying an occasional martini at Antonio’s Nut House, spending time with family and friends, and keeping in touch with former colleagues and students. His house, lined with books and personal artwork, is considered by many to be an unofficial museum. He was appreciated for his clever poems and creative Christmas cards.

Charles was preceded in death by his wife, Margot, and his daughter, Nadja May. He is survived by his two sons, Peter (Amy Adams) and their son, Aidan, and Kai (Sarah) and their daughters, Emily and Beatrice, his sister, Mary Alice Stephen, and numerous nieces and nephews.

Midtown History: Charles and Margot Drekmeier (aka Peter's parents)

(Photo credit: Courtesy of the family)

Charles hails from Wisconsin. Halfway through his years at the University of Wisconsin, he was inducted into the army. World War II had obligingly ended—he never was asked to do much damage, and he returned to the University of Wisconsin. After getting an MA in history at Columbia, Charles taught at Boston University and spent a year in India writing a book on ancient Indian Political and social thought.

Margot hails from Boston. She is a graduate of Oberlin where she was president of the student council and later was on the alumni board. Margot also had a Fulbright—hers to Paris where she wrote a dissertation on eighteenth century abbés who were more in interested in the parties of salon hostesses than in ecclesiastical affairs.

The two met as graduate students at Harvard and were married a month after Margot's return from France.

And, in another month, Charles—having been offered a job in sociology at Stanford (at $3600)—they were on their way west in one of the first VW microbuses, with a Vespa scooter and their other worldly goods tucked inside. They vividly recall a moment in the mountains, entering Wyoming from South Dakota, when the vehicle was moving backward faster than it was going forward. (Further details spared.)

At Stanford, Charles sometimes felt he was in a situation comparable to the VW: teaching political sociology, sociology of religion, bureaucracy, sociological theory, psychoanalysis and social structure, and social psychology. Some of these “courses” he never had as a student. But during his second year he succeeded in insinuating himself into the political science department. Now, of course, half in political science and half in the sociology, he had twice the drudgery of departmental committees. A Carnegie Endowment, with a grant for a year at Harvard Law School, allowed him time to develop a general course in the history of political theory, and he was now back in familiar territory when the political scientists accepted him into their ranks. Margot continued in the Western Civilization program and taught seminars on Galileo, Rousseau and his contemporaries, psychoanalysis and history.

Charles retired from teaching in 1998, and Margot earlier when the children began to arrive: first Nadja, who is now a social worker in Chico; then Peter, an environmental activist (as he described himself in the voter's manual) and now a member of the Palo Alto City Council; finally, in 1968, Kai, a founder of Score! (a computer-assisted learning project) and now launching a program to help students at these two-year technical schools keep from failing. As of this writing there is one grandchild, Emily Olive. Because the Dreks are an endangered species (we're the last), subtle hints are dropped from time to time suggesting that Kai and his wife Sarah produce a brother for Emily and that Peter should not devote all of his time to the further greening of Palo Alto.

The children have gone in several directions, but most are within a few hundred miles of the old homestead—an Eichler house which exists comfortably among fifteen others in a cul-de-sac which Charles believes is the second-oldest in the city. There isn’t quite the same sense of community that existed in 1962 when the Dreks bought the house (for a price that could make you sigh). “Most of the neighbors boarded a vessel belonging to the family across the street and we all sailed off to Alviso for an Italian dinner. For a number of years we paid the police department five or ten dollars to close off the street for our block parties.” Two of the families had ten children each and one of the matrons still lives here. But the Dreks are the second most senior inhabitants. It is a far more cosmopolitan neighborhood now. Charles estimates that English is the second language for half the families. Although much has changed and the old neighbors are gone, the street still floods from time to time, the raccoons still threaten the cats, and the eucalyptus trees keep people busy in their yards.

Looking back, Charles and Margot see the ‘60s as the high point of their academic life. Charles was invited to start a political science department at Rice in Houston (their political scientists were housed with the historians) and this seduction got him tenure at Stanford. That, Houston's weather, and the possibility that Lyndon Johnson would join the new department after he left Washington, encouraged Charles and Margot to stay in California. Within a year or two, as the Vietnam War was heating up, it became clear to them and a number of their colleagues that academics had the responsibility of analyzing the disaster unfolding in southeast Asia. Charles and Claude Buss of the History Department chaired an all-day 'teach-in' utilizing the various specialties of the Stanford faculty. Teach-ins blossomed all over the scholarly map but only Michigan was ahead of Stanford.

At the behest of activist students, Charles and six other faculty from the social sciences arranged for thirty students—fifteen black and fifteen white—to join Martin Luther King in 'Resurrection City,' a project planned for Washington DC. For there to be academic credits, the students had to pursue a course of study that included everything from the techniques of participant observation to the history of the civil rights movement. Their commitment pushed them to work hard, and the two grad students who worked as teaching assistants said they'd never seen such devotion to studies. Alas, on the day before they were due to leave for Washington, Rev. King was assassinated. The tents of Resurrection City never went up.

Heavy times those. The two Drekmeiers, along with Bud McCord (Dean and Sociologist), started a new social science program in 1959 called Social Thought and Institutions. Really an honors seminar, it lasted for twenty-three years until 1983. One could major in Social Thought provided he or she wrote an acceptable honors thesis in the second year of the two-year program. There were never more than fifteen students and the instructors usually numbered four. Over the years, twenty Stanford faculty were involved. One concept or idea would be examined during the year—perception, revolution, motivation, myth and symbol were some of them. The group met once a week, usually at the Drekmeiers. Since it was a labor of love and no salaries were paid, they were free of decanal interference. A true collegiate operation. The Drekmeiers viewed those Thursday evenings as a sort of refuge. And their children, listening from the hallway, say it was a learning experience for them, too.

When, during that feverish year, 1968, the family was invited to participate in the Stanford Overseas program—specifically a quarter at the English campus and a quarter in Vienna—it seemed to be a good time to relax a little and get to know the children better. Stanford had leased a huge manor house from the Jesuits in the vicinity of Grantham (Newton country) in Lincolnshire and the Dreks settled in on New Years' Eve. Charles lectured on English political thought from the Magna Carta to Churchill, holding forth from the pulpit in the chancel. He and Margot gave a seminar on English contributions to psychological theory. It was at Harlaxton Manor that Peter and Nadja saw snow for the first time. Students were not above taking advantage of this hyper 3½ year old, and Peter was used to initiate food fights and such. Nadja seemed to identify with the students and enjoyed their attention. Then on to Vienna and German idealist theory, the byways of interpretation, and all that. The 'palast' was only two blocks from the Staatsoper with its many temptations. The famed pianist, Paul Badura-Skoda, could be heard practicing below while Charles held the students, not quite spellbound on Kant and Hegel.

Charles Albert Drekmeier,

Lasting Memories, Palo Alto Online. Link

Midtown History: Charles and Margot Drekmeier

(aka Peter's parents),

by Annette Ashton, Midtown Residents Association. Link

Memoir,

by Charles Drekmeier with assistance from Don Kazak, www.drekmeier.org. Link

“Drekmeier was a social theorist known for work with students,” by Sandra Feder, Stanford News, 23 September 2020. Link

Interview with Charles Drekmeier by Peter Steinhart, 2016, Stanford Historical Society, Oral History Program. Link

In this interview, Professor of Political Science, Emeritus, Charles Drekmeier, discusses his academic training with Talcott Parsons and others, his interests in political theory and social thought, the development of the Stanford Program in Social Thought, and civil rights and anti-Vietnam War activism on the Stanford campus during the 1960s and 1970s.

Interview with Charles Drekmeier by Natalie Marine-Street, 2017, Stanford Historical Society, Oral History Program. Link

Professor Emeritus Charles Drekmeier, who served as a member of the Executive Committee of the Academic Council from 1966 to 1968, describes the general climate at Stanford around the time that the Faculty Senate was formed. He discusses the circumstances that led to his arrival at Stanford in 1958 and recalls how, as a young faculty member with a student following due his involvement in early anti-Vietnam war activism, he was invited to be an at-large member of the Executive Committee of the Academic Council in 1966. He offers recollections of key movers in academic governance at the time, including J.E. Wallace Sterling, Albert Guerard, Richard Lyman, Herb Packard, Ernest Hilgard, and Kenneth Arrow, and recounts memories about organizing the Stanford Teach-In on the Vietnam War in 1965 and the program in Social Thought and Institutions.