April Third Movement

David Harris

David Harris, an activist and journalist who in the late 1960s became a national figure for encouraging young men to resist being drafted to serve in the Vietnam War—and who went to jail after refusing the draft himself—died on Monday (Feb. 6, 2023 ed.) at his home in Mill Valley, Calif. He was 76.

His wife, Cheri Forrester, said the cause was lung cancer.

Mr. Harris was an unlikely avatar of the antiwar movement. The son of a lawyer and a religiously conservative mother in California’s Central Valley, he entered Stanford University in 1963 after being elected boy of the year

by his high school, where he debated and lettered in football.

But a freshman year awakening, including a few weeks working in Mississippi at the end of Freedom Summer in 1964, persuaded him that his generation had a moral obligation to fight injustice, including what he saw as the unfolding disaster in Vietnam. Over the next several years, he used his establishment standing to rise to national prominence, calling on his fellow students and other young people to confront the draft head on.

Though he was sometimes labeled a draft dodger, he was very much the opposite. He advocated resistance, not avoidance, urging his fellow students to return their draft cards to the government in protest.

Doing so was a felony, and when Mr. Harris himself was drafted, in 1968, he refused to report for induction. He was almost immediately indicted by the federal authorities.

I dodged nothing,

he wrote in a guest essay for The New York Times in 2017. I courted arrest, speaking truth to power, and power responded with an order for me to report for military service.

A few months after his indictment, he married the singer Joan Baez, whom he met through the antiwar movement. The two had been touring the country for 16 months, with her singing and playing guitar as a warm-up to his antiwar stemwinders.

There wasn’t any question to me that this guy had enormous talent for speaking,

Ms. Baez said in a phone interview. We’d go around, do this dog and pony show, and I would open up for him, singing, and people would all get together to hear David Harris talking about how we’re going to change the world.

Mr. Harris was convicted in 1969 and sentenced to three years in federal prison, of which he served 20 months. Soon after his sentencing, Ms. Baez wrote A Song for David, in which she lamented, The stars in your sky/Are the stars in mine/And both prisoners/Of this life are we.

He was released in 1971, but life out of prison was a tough adjustment for him, both personally and professionally. The war was beginning to wind down, as was the antiwar movement. He and Ms. Baez divorced a few months later, though they remained close friends the rest of his life.

On a whim, he wrote a letter to Jann Wenner, the publisher of Rolling Stone magazine, offering to sell him a series of antiwar essays. Mr. Wenner demurred, but he liked Mr. Harris’s writing enough to let him try something else: a profile of Ron Kovic, a Marine whose battlefield injuries in Vietnam had left him unable to use his legs, and who went on to be a prominent antiwar activist.

The article, Ask a Marine,

ran in 1973. Three years later Mr. Kovic published his autobiography, Born on the Fourth of July, and in 1989 Oliver Stone made a critically acclaimed film version of the book, starring Tom Cruise as Mr. Kovic.

The article also launched Mr. Harris’s second career, as a magazine journalist and author. He spent the next five years writing for Rolling Stone and in 1978 became a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine. A decade later, he left the magazine to write books full time.

His journalism often mined the legacy of the Vietnam War and the social tumult of the 1960s. It included a searching piece about one of his Stanford mentors, the liberal activist and politician Allard K. Lowenstein, who in 1980 was murdered by Dennis Sweeney, another former Stanford student and a friend of Mr. Harris.

Back in the early 1960s, dreams of making the world better were still envisioned as simple things,

he wrote. “No one yet had seen visions warp under the weight of the reactions they would produce.”

David Victor Harris was born on Feb. 28, 1946, in Fresno, Calif., the son of Clifton Harris Jr., a rock-ribbed Republican lawyer, and Elaine (Jensen) Harris, a homemaker.

He grew up amid the affluence generated by California’s postwar boom. A top student at Fresno High School, he dreamed of going to West Point and becoming an F.B.I. agent, but ended up at Stanford.

He lived in the same dorm as Mitt Romney, the future Republican presidential candidate, though their social and political paths rarely crossed.

Mr. Harris was soon drawn to a group of students involved in the civil rights movement, and he begged his father to let him join them on a trip to Mississippi in the summer of 1964. His father insisted that he instead stay home and work.

I came back for the start of my sophomore year afraid that I had missed the great adventure of my lifetime,

he said in a phone interview for this obituary last year.

But when he heard that some of the students were planning to go back to Mississippi for another round of organizing, he signed up immediately. Within three days he was on the ground in Lambert, a Delta town about 75 miles south of Memphis.

The experience electrified him. He returned to school later that fall and immersed himself in Stanford’s nascent movement against the Vietnam War. He spent long nights in his room with his dorm mates, listening to music (including Joan Baez records, long before he had met her) and debating the morality of America’s military involvement in Southeast Asia.

He attended his first protest in March 1965. The experience, he wrote in his book Our War: What We Did in Vietnam and What It Did to Us (1996), felt like an emergence, from dark into light, from forest into clearing.

He centered his activism on draft resistance, because, he said, it was a way for him to make a personal, concrete difference—and, possibly, a sacrifice. In 1966 he mailed his draft card back to the U.S. Selective Service, writing that he would refuse to carry it and would decline to serve if he were drafted.

I sealed the envelope, walked down the block to the mailbox and put the envelope in,

he wrote. I remember that summer afternoon, the dirt of the road nearby, and I remember feeling like I could have flapped my arms and flown back to my house if I had wanted. I felt like I was my own man for the first time in my life.

A gifted orator, Mr. Harris was soon in demand as a speaker at antiwar rallies across California. Along the way he encountered Ms. Baez, who had founded an organization called the Institute for the Study of Nonviolence, in Carmel, Calif. One day Mr. Harris drove down there looking for grant money.

He was just this lovely cowboy,

Ms. Baez said. And that was my introduction to what the resistance was all about. I mean, I knew a little, but he was certainly the best representative to have.

At the start of his senior year, Mr. Harris was elected student body president on a platform focused on righting the unequal status of women at Stanford. He made national news when, a few months into the school year, a group of pro-war Stanford students grabbed him and shaved him bald as punishment for his activism.

He was unmoved, displaying a stoicism that he carried into the courtroom during his trial for refusing the draft.

There comes a time when you have to prove who you are,

he told Alta magazine in 2019. I had to stand up in court and tell the judge that I knew there were six technicalities in my record with the Selective Service system that were grounds for throwing the whole case out. But that I didn’t want to exercise them, because I wanted this to be decided on the issue.

In prison he led hunger strikes to improve conditions for inmates, first at a minimum-security camp in Arizona and then at a more rigidly controlled prison in Texas, where he had been sent as punishment.

Mr. Harris married Lacey Fosburgh, a writer and former reporter for The New York Times, in 1977. She died in 1993. He met Ms. Forrester in 1993, and they married in 2011.

Along with his wife, he is survived by his son with Ms. Baez, Gabriel Harris; his daughter with Ms. Fosburgh, Sophie Harris; a stepdaughter, Eva Orbuch; a granddaughter; and his brother, Clifton Harris.

After leaving The New York Times Magazine, Mr. Harris wrote several investigative books about sports, politics and the environment, including, most recently, My Country ’Tis of Thee: Reporting, Sallies and Other Confessions (2020), a collection of his newspaper and magazine articles.

That golden age of journalism I was blessed to participate in is over now,

he wrote at the beginning of that book, but my faith in that lost era’s tenets remains. Hopefully this look back over those decades will help in its own small way to seed another golden age in which Truth outranks all comers.

Celebrating the Life, Activism,

and Writing of David Harris

Stanford University

October 26, 2023

YouTube Link

Mark Paul

In September, 1969, a couple of months after David entered federal prison, I moved into the room at the end of the first floor of Rinconada house, where I was to be a freshman sponsor. When I opened the dresser to stow my things, I had a surprise and a wave of self-doubt. David Harris, who had, unbeknownst to me, served as a sponsor four years earlier, had inscribed his name on the inside of the top drawer. It told me I had big shoes to fill.

David left a bigger mark on that place than his scrawled signature. When one of the freshmen on his floor was fingered for hosting his girlfriend overnight in his dorm room, David refused the faculty resident’s demand that he file charges against the young man. That refusal, along with his presidential campaigning against the parietal rules then in force, went far toward making the Rinconada house I sponsored in 1969 a much freer and humane place for my housemates.

One other thing in that story stands out. The girl involved ended up being suspended for six months,

David remembered. Not so the 34 masked fraternity men who the following year lured David to an ambush, dragged him in the dark into the bushes, bound his legs with tape, pinned his arms to the ground, and forcibly shaved his head. They were placed on probation.

At the Stanford we entered, love was a punishable offense; violence, or at least violence against the right victims, not so much.

Thank you, David Harris, for fighting so hard to change that.

David Shulman

It’s difficult to express how inspiring David Harris was for me. I first started tracking him when I was still in high school, moved by his election as Stanford student body president, stunned that fraternity members grabbed him and shaved his head, his moral arguments that white, privileged students had a duty to resist the draft, and his courage in doing just that, eventually going to prison rather than avoid being found guilty at trial despite knowing there were six separate technicalities upon which he could have gotten his case thrown out. His stance was not about technicalities, it was about the wrongness of the war, and his obligation, as a man of privilege, to do what poor, disenfranchised men—disproportionately Black or brown—who had no options, could not afford to do: resist.

My first day at Stanford, a friend and I hitchhiked from SFO to Palo Alto. It seemed like more than coincidence when the driver dropped us off at Draft Resistance headquarters, a storefront on University Avenue Harris and other resisters had founded. They were draft resisters, not dodgers, As the New York Times pointed out in his obituary, they were resisters, not dodgers, and that meant active engagement to express their point of view as effectively and personally as they could. By chance, I was still 17 when school started, for as a product of California public schools, November babies started kindergarten at age four, the enrollment cutoff date being December 2. That meant that when that driver dropped us off, I knew I would be returning to that storefront for help in wrestling with whether I would cooperate with that legal obligation.

I was counseled by a resister who was awaiting the start of his prison term; Harris was already in prison. I have never forgotten that resister’s kindness, and the respect he expressed towards my moral struggles—no guilt-tripping, holier-than-thou-stance here, no siree. There was no room for that at the depth at which these men—and the women who were supporting them—were operating. I was profoundly moved by the courage of their example, but conflicted over how resisting threatened the wonders and opportunities entrance to Stanford had just afforded me. More difficult yet to admit, I also felt too young to be making such a momentous-decision, especially since Harris and my counselor and most of the other resisters—most, but not all—were a few years older than I. Moreover, there felt something time-specific about their action, that the first wave of resisters in 1968 had made an impact. It was unclear to me that a second, younger wave would have a similar one, especially with a draft lottery imminent. I later learned that Harris was just as kind and supportive in private of such struggles as my counselor, a sharp and moving complement to the vigor and courage of his public advocacy. I decided to stay in school, and a year and a half later came under the influence of two of the Stanford professors who had sharpened and affected Harris’s thinking and moral growth—Margot and Charles Drekmeier—and accompanied them to hear Harris’s first public address—at Stanford’s Memorial Church—following his release from prison.

Eleven years later, my regard for Harris grew all the more so upon reading his memoir Dreams Die Hard: Three Mens’ Journey Through The Sixties. He was a journalist by then, and the jumping off point for the memoir was being awakened early one morning in March 1980 by calls from fellow journalists asking for comment on the news that the previous day, fellow activist and resister Dennis Sweeney had walked into the law office of Allard Lowenstein, a mentor to them both, and shot him to death. As Stanford’s dean of students, Lowenstein had inspired a generation of young, idealistic students like Harris and Sweeney, and in 1964, both of them went to Mississippi to participate in the historic—and dangerous—effort to register Black residents to vote. That was the summer after Dr. King’s I Have a Dream

speech, and white terrorists’ answer to it just a few weeks later by dynamiting a Black Birmingham church on a Sunday morning, killing four little girls.

That next summer began with white terrorists kidnapping and murdering three of the Mississippi voting rights activist—Mickey Schwerner, Andrew Goodman and James Chaney—in a failed attempt to halt the project before it gained traction and moral ground. Another terrorist strike was a bomb that went off in the middle of the night on the front porch of a Black family’s home where Sweeney and others were staying that knocked Sweeney to the floor. With sensitivity and nuance, Harris established that this trauma to Sweeney may have been one of the factors that contributed to Sweeney’s frank psychotic break a few years later, leading him to blame Lowenstein for the CIA-implanted radio transmitters in the fillings of his teeth, and such further deterioration as to finally lead him to his horrifically murderous act. Harris spared no one in his memoir, not himself, not Sweeney, not Lowenstein for their personal shortcomings, along with the indictable systemic failures of America in those years first of civil rights and then, antiwar activism. The memoir is all the more remarkable for the wry wisdom and kindness he showed writing about his relationship and marriage to Joan Baez during some of those years, a maturity and compassion evident once again in their joint appearance on PBS’s American Masters program on Baez, and again in her own grieving Facebook post announcing his death, a screenshot of which I’ve posted below.

The rest of Harris’s life continued a remarkable arc, as recounted in The New York Times’ obituary, and on his own homepage (see links below), and his draft resistance leadership is well-told in an important documentary, Boys Who Said No!, which, fortunately, was completed before he became too ill to participate (also linked below).

During the pandemic, I came across the audio of the eulogy Harris gave for the professor we’d both admired—Charles Drekmeier. I was once again so moved by his words—his moral sensitivity, his understanding of others, his fierce intelligence, and compassion—that, this time, I reached out to him to talk about Charles and Margot. Fifteen months ago, that resulted in an hour-long zoom conversation I’ll remember for the rest of my life. He was quite ill by then, having already been living with Stage 4 cancer of both the lungs and the prostate since 2018, but he was all there, patient and respectful as I quickly sketched my place in the Stanford activist lineage he had done so much both to advance and illumine, touched by the updates I could share about the Drekmeiers, clear-eyed and at peace with his role in things, without an ounce of ego or self-aggrandizement about it all, still a tough old buzzard, as is apparent in a final major interview, also linked below.

David Harris Might Be Dying, but He Continues to Resist,by Alan Goldfarb, Alta Journal, November 4, 2019. Link

Bill Bower

I wasn’t close to David, but he spoke to my freshman class during orientation. I’d say it changed my life. I took to heart that he said each of us is responsible for the choices that we make.

And I chose to oppose the war in Vietnam, to not accept a student deferment. Then I worked with grass roots rural health programs in Mexico and Central America for many years, before going to Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health.

Reflections of an Activist: David Harris

David Harris was interviewed on March 19, 2021, as part of The Movement Oral History Project. The interview is available as a video file, an audio file, and a text file (transcript).

David Harris (Class of 1967) reflects on his undergraduate years at Stanford in the 1960s, focusing on his time as student body president and the factors that shaped his work as an activist in both the civil rights movement in Mississippi and the movement against the Vietnam War. He also shares memories of the time he spent in prison for draft resistance and offers his impressions on politics and Stanford today.

1969—Stanford and the World

David Harris gave the keynote address at the 40th anniversary of the April 3rd Movement on May 15, 2009. He reflected on activism in the Sixties and its political and personal significance.

I Picked Prison Over Fighting in Vietnam

Growing up in Fresno, Calif., I believed in

Growing up in Fresno, Calif., I believed in my country, right or wrong,

just like everyone I knew. I could not have anticipated that when I came of age I would realize that my country was wrong and that I would have to do something about it. When I did, everything changed for me.

I went from Fresno High School Boy of the Year 1963, Stanford Class of 1967, to Prisoner 4697-159, C Block, maximum security, La Tuna Federal Correctional Institution, near El Paso.

I was among the quarter-million to half-million men who violated the law that required us to register for military service and face deployment to Vietnam—the draft. About 25,000 of us were indicted for our disobedience, almost 9,000 convicted and 3,250 jailed. I am proud to have been one of the men who, from behind bars, helped pull our country out of its moral quagmire.

I was just 20 when I first stepped outside the law. After months of late-night dorm-room conversations and soul searching, I decided doing so was my duty as a citizen. It was 1966 and draft calls were escalating every month as the American Army in Southeast Asia built up to half a million men, dozens of whom were coming home in coffins every week. I had just been elected Stanford student body president on a radical

platform calling for an end to the university’s cooperation with the war, and I had already refused to accept a student deferment that would have allowed me to avoid the draft and probably sent a poor person in my stead. But I knew that even such valuable protest was an insufficient response to the moral arithmetic of sending an army thousands of miles from home to kill more than two million people for no good reason.

At stake was not just the nation’s soul but mine as well. So I took the draft card I was required by law to have at all times and returned it to the government with a letter declaring I would no longer cooperate. Carrying that card had been my last contribution to the war effort. If the law was wrong, then the only option was to become an outlaw.

Some would call me a draft dodger, but I dodged nothing. There was no evasion of any sort, no attempt to hide from the consequences. I courted arrest, speaking truth to power, and power responded with an order for me to report for military service. While delaying that order with a succession of bureaucratic maneuvers, I helped found the Resistance, an organization devoted to generating civil disobedience against conscription. Three or four of us lived out of my car and crashed on couches, going from campus to campus, gathering a crowd and making a speech, looking for people willing to stand up against the wrong that had hijacked our nation.

On Oct. 16, 1967, the Resistance staged its first National Draft Card Return, during which hundreds were sent back to the government at rallies in 18 cities. We staged more rallies and teach-ins. Hundreds more draft cards were returned, at two more national returns as well as individually or in small groups. We provided draft counseling for anyone, whether he wanted to resist or not.

At draft centers, we distributed leaflets encouraging inductees to turn around and go home. At embarkations, we urged troops to refuse to go before it was too late. We gave legal and logistical support to soldiers who resisted their orders. We destroyed draft records. We arranged religious sanctuary for deserters ready to make a public stand, surrounding them to impede their arrest. We smuggled other deserters into Canada. We even dug bomb craters in front of a city hall in Florida and posted signs saying that if you lived in Vietnam, that’s what your front lawn would look like.

Then we stood trial, one after another. Most of us were ordered to report for induction, then charged with disobeying that order, though there were soon so many violators that it was impossible to prosecute more than a fraction of us.

I was among that fraction. On Jan. 17, 1968, I refused to submit to a lawful order of induction.

I had my day in court that May. As was the case in almost every draft trial, my judge refused to allow me to present any testimony about the wrong I had set out to right, saying the war was not at issue. Nonetheless, my jury stayed out for more than eight hours before finally convicting me. I was sentenced to three years. I appealed my conviction, but abandoned that appeal in July 1969 and began my sentence.

My fellow resisters and I brought our spirit of resistance to the prison system, organizing around prisoner issues of health care, food and visits. I was a ringleader in my first prison strike while still in San Francisco County Jail, awaiting transfer. After being sent on to a federal prison camp in Safford, Ariz., I was in three more strikes, at which point I was shipped to La Tuna. My first two months there, I was locked in a punishment cellblock known as “the hole” with three other ringleaders from Safford. When I was finally moved upstairs, I learned that our Army had expanded the war into Cambodia several weeks earlier.

My home was 5 feet by 9 feet. I was frisked when I was sent to work in the morning, when I returned from work in the afternoon and when I both left for and returned from evening recreation.

Doing time well required a Buddhist state of mind, of being present where you are and not thinking of yourself in places where you couldn’t be. The latter is slow torture for a prisoner. Doing time well also required being your own person despite the guards’ efforts otherwise. They’ve got your body,

we used to say, but they can only get your mind if you give it to them.

The result, in my case, was a running series of disciplinary violations for the likes of refusing to make my bed and return trips to the punishment cellblock.

Nonetheless, the parole board released me on March 15, 1971. The war was still going on; not long after I first reported to my parole officer, a group of Vietnam veterans protested the war in Washington and threw the medals they’d been awarded onto the steps of the Capitol.

Draft calls were now steadily shrinking as air power replaced ground troops, and military conscription would soon be gutted altogether. My parole ended the following summer. I stopped organizing eight months later when peace agreements were finally signed.

Several years after that, I was invited to testify at a Senate hearing considering pardons for our draft crimes. I told the senators I had no use for their forgiveness, but I would accept their apology. I’m still waiting to hear back from them on that.

I am now 71 and the war that defined my coming of age is deep in my rearview mirror, but the question it raised, What do I do when my country is wrong?

lives on.

For those looking for an answer today, here are some lessons I learned:

We are all responsible for what our country does. Doing nothing is picking a side

We are never powerless. Under the worst of circumstances, we control our own behavior.

We are never isolated. We all have a constituency of friends and family who watch us. That is where politics begins.

Reality is made by what we do, not what we talk about. Values that are not embodied in behavior do not exist.

People can change, if we provide them the opportunity to do so. Movements thrive by engaging all comers, not by calling people names, breaking windows or making threats.

Whatever the risks, we cannot lose by standing up for what is right. That’s what allows us to be the people we want to be.

David Harris, Activist Jailed over Vietnam Draft Resistance, Dies at 76

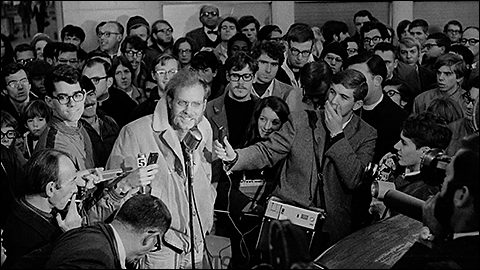

Photo by Bob Fitch, Stanford University Libraries Archive

David Harris, an antiwar activist and writer who became a symbol of Vietnam-era draft resistance by refusing conscription and serving 20 months behind bars after virtually demanding a jail sentence, died Feb. 6 at his home in Mill Valley, Calif. He was 76.

His daughter Sophie Harris said the cause was lung cancer.

Mr. Harris often recounted his personal evolution: Raised in a politically conservative California home with visions of careers in the military or the FBI, he was jolted into a new perspective during his sophomore year at Stanford University while helping register Black voters in Mississippi in 1964.

Afterward,

he said, I didn’t look at America in the same way.

Amid the many fronts in the opposition to the Vietnam War, Mr. Harris developed a powerful voice calling for mass civil disobedience in speeches at college campuses and at concert-and-protest events along with his future wife, folk singer Joan Baez.

Mr. Harris asked young men facing the draft to refuse to register with the Selective Service or return draft cards to authorities. For Mr. Harris, defiance at home was a stronger statement than fleeing to Canada or other countries to avoid service.

Inspired by Mr. Harris and others, tens of thousands of people joined protests to burn draft cards or reject the process from the beginning. In one of the most publicized rebuffs to the war, boxer Muhammad Ali was convicted in 1967 after refusing induction into the military. (The Supreme Court overturned Ali’s conviction in 1971.)

At an antiwar rally in 1967, Mr. Harris told crowds at San Francisco’s Kezar Stadium that U.S. policies in Vietnam would not change until the country was confronted by young men who will not murder.

Mr. Harris’s stature in the antiwar movement was perhaps less prominent than national figures such as Pentagon Papers leaker Daniel Ellsberg, Yippies co-founder Abbie Hoffman or future California state lawmaker Tom Hayden.

Yet among young men facing conscription, Mr. Harris became a champion for his fiery oratory against the war and the economic inequities of the draft — which allowed deferments for college undergrads and skewed conscription toward less privileged and minority recruits.

I dodged nothing,

Mr. Harris wrote in a 2017 essay in the New York Times. I courted arrest, speaking truth to power, and power responded with an order for me to report for military service.

Mr. Harris knew the showdown was coming. He left Stanford in 1967 before graduation. Then, for more than a year, he had been speaking out against the war in a roadshow that included Baez, a superstar in folk music who had helped launch the career of Bob Dylan and was featured on the cover of Time magazine in 1962.

When he was drafted in 1968, he refused to report for induction. He was quickly indicted. The next year—after Mr. Harris and Baez were married—he said he purposely rejected any options to avoid conviction, fearing his credibility would be shattered.

So I ended up in court, standing up and saying, ‘I know that this case should be thrown out, but I’m not going to do that,’he recounted in a 2008 interview.

He was sentenced to three years in federal prison. It was an unusually harsh punishment. The Selective Service referred 184,135 men to the Justice Department for prosecution during the Vietnam War. Of those, 8,756 were convicted and 4,001 were imprisoned, according to the 2020 documentary “The Boys Who Said No!”

At the federal prison in La Tuna, Tex., Mr. Harris spent a total of four months in solitary confinement for organizing inmate protests for better food and other improvements. Baez wrote A Song for David (1970) while he was incarcerated. And both prisoners,

she wrote in the lyrics, of this life are we.

When he was paroled in 1971, however, he emerged a different person,

he said. He returned to antiwar activism, but his passion and focus appeared to wane. He and Baez divorced in 1973.

About that time—with the Vietnam War in its final years—Mr. Harris reached out to Rolling Stone magazine to propose a series of antiwar essays. Publisher Jann Wenner instead gave Mr. Harris an assignment to profile Ron Kovic, a Marine who lost the use of his legs from injuries in Vietnam and returned to become an outspoken critic of the war.

The piece ran in 1973. Three years later, Kovic published his autobiography, Born on the Fourth of July, which Oliver Stone made into a 1989 film starring Tom Cruise.

Mr. Harris moved into a writing career, contributing further pieces to Rolling Stone as well as to the New York Times, and writing books that ranged in topics from the National Football League to California’s Redwood forests to the 1980 killing of peace activist and former New York congressman Allard Lowenstein. In 1976, Mr. Harris made an unsuccessful run as a Democrat against Rep. Pete McCloskey (R-Calif.).

His 1976 memoir, I Shoulda Been Home Yesterday, recounted his time in prison, and Our War: What We Did in Vietnam and What It Did to Us (1996) looked back on how the 1960s divisions never fully healed.

Did I have any doubts about what we were doing? You bet,

he said in 2019 about his antiwar activism. Here was a bunch of 20-year-olds taking on the most powerful entity in the world, and all we had was a printing press out in the garage to make fliers.

Gandhi as ‘hero’

David Victor Harris was born in Fresno, Calif., on Feb. 28, 1946. His father practiced law and was an officer in the Army Reserve.

In high school, Mr. Harris was elected boy of the year

and said he had ambitions of becoming an FBI agent or going to the U.S. Military Academy. I was absolutely straight. Fresno had no radicals in those days,

he told Marin magazine.

During his sophomore year at Stanford, he begged his parents to allow him to join the freedom riders

heading to the Deep South. One night in Lambert, Miss., Mr. Harris said, a White man aimed a shotgun at his face and warned he had five minutes to leave town. Friends loaded Mr. Harris into a car and drove off.

Back in Stanford, he immersed himself in the works of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., political philosopher Hannah Arendt, Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh and Mahatma Gandhi, who became his “personal hero.”

Mr. Harris wrote that joining his first antiwar protest in March 1965 was like emerging from dark into light, from forest into clearing.

One dorm resident, future U.S. senator Mitt Romney (R-Utah), was not part of Mr. Harris’s social circle, but Mr. Harris made at least a few attempts to bring Romney into the antiwar camp. Romney would not budge.

In his senior year, Mr. Harris was elected student body president and became the subject of national headlines when he had his head forcibly shaven by students in favor of the Vietnam War.

In 1977, Mr. Harris married Lacey Fosburgh, a journalist and author who died 1993. He married Cheri Forrester in 2011. Survivors also include a son from his first marriage; a daughter from his second marriage; a stepdaughter; a brother; and a granddaughter.

Mr. Harris said he was raised to accept an airbrushed version of the United States as a paragon of justice and rights.

It was our assumption that America was the bastion of all things good,

he said in 1982 for a PBS series on the Vietnam era. And it was precisely that assumption that made us the kind of disillusioned people we were at the end.

David Harris, Leader of Vietnam Draft Resistance Movement, Dies at 76

, by Clay Risen, The New York Times, February 9, 2023. Link

David Harris, Activist Jailed over Vietnam Draft Resistance, Dies at 76,

by Brian Murphy, The Washington Post, Feb. 8, 2023. Link

Stanford Remembers

Mark Paul, Personal Communication. Mark Paul is co-author of California Crackup: How Reform Broke the Golden State and How We Can Fix It.

David Shulman, Personal Communication.

Bill Bower, Personal Communication.

About David

David Harris Might Be Dying, but He Continues to Resist,

by Alan Goldfarb, Alta Journal, November 4, 2019. Link

David Harris,

by Jim Wood, Marin Magazine, December 19, 2008. Link

David Harris & Joan Baez, 1967–2014,

The Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Stanford Libraries. Link

The Connie Vote: The USS Constellation and the Peace Movement in San Diego, 1971,

The Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Stanford University Libraries archive. Link

In Memory and in Honor of David Harris,

Edward Hasbrouck’s Blog. Link | Also Draft Resistance News

. Link

“David Harris (activist),” Wikipedia. Link

In David's Own Words

I Picked Prison Over Fighting in Vietnam,

by David Harris, The New York Times, June 23, 2017. Link

Also available at davidharriswriter.com.

“Draft Resistance, 80’s Style,” by David Harris, The New York Times Magazine, August 22, 1982, Link

David Harris: Author, Journalist, Activist (David Harris’s Website). Link

Videos

“Reflections of an Activist: David Harris,” The Movement Oral History Project, Stanford Libraries, March 19, 2021; video file, audio file, and text file (transcript). Link

“David Harris—1969, Stanford and the World.” Keynote Address during the A3M Reunion Celebrating the 40th Anniversary of the April 3rd Movement; Introduced by Jeanne Friedman; May 15, 2009, Midpen Media Center, YouTube; Video, 43:10. Link

Vietnam: A Television History; Interview with David Harris, August 10, 1982. Boston, MA: GBH Archives; Video, 41:10. Link

Shooting the Moon: The True Story of an American Manhunt Unlike Any Other, Speech by David Harris at Book Passage [bookstore], Corte Madera, California, May 22, 2001, broadcast on C-SPAN2 TV, Video, 53:22. Link

“Celebrating the Life, Activism, and Writing of David Harris,” Stanford University, October 26, 2023. YouTube Link

Audio

“Mr. Peace on Modern Resistance,” David Harris interviewed by Beth Spotswood, Alta Magazine Audio Podcast, Nov. 6, 2019; Auido, 18:37. Link

“David Victor Harris,” Interview with Stephen McKiernan, Binghamton University, State University of New York Libraries, November 6, 2009; Audio, 1:27. Link

“David Harris on Draft, White Plaza,” Stanford University News and Publications Service, January 24, 1980; Audio, 46:09. Link