April Third Movement

H. Bruce Franklin

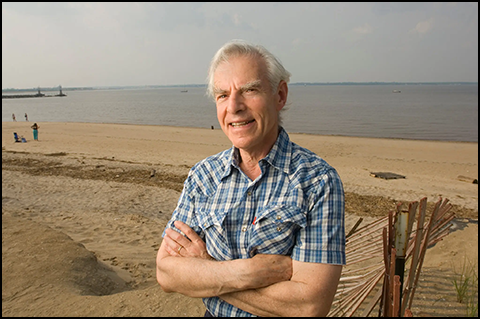

Bruce Franklin, Rest in Power!

H. Bruce Franklin, Scholar Who Embraced Radical Politics, Dies at 90

A cultural historian, he was fired by Stanford University in 1972 over an anti-Vietnam War speech that became a cause célèbre of academic freedom.

H. Bruce Franklin, a self-professed Maoist whose firing by Stanford University in 1972 over an anti-Vietnam War speech became a cause célèbre of academic freedom — and who in the ensuing decades wrote books on eclectic topics, including one credited with helping to improve the ecology of New York Harbor — died on May 19 at his home in El Cerrito, Calif., near Berkeley He was 90.

The cause was corticobasal degeneration, a rare brain disease, his daughter Karen Franklin said.

Dr. Franklin was a tenured English professor and the author of three scholarly books about Herman Melville when he became radicalized in the 1960s over the Vietnam War, a process that accelerated after he spent a year in France, where he and his wife, Jane Franklin, met Vietnamese refugees whose relatives had been killed by U.S. forces.

“When we came back to this country, we were Marxist Leninists, and we saw the need for a revolutionary force in the United States,” Dr. Franklin told The New York Times in 1972.

His far-left politics, to the point of endorsing violence, mirrored extreme currents running through the country and the culture in that era, a mix of revolutionary theatrics and genuine threat.

Back at Stanford, he and his wife helped form a group called the Peninsula Red Guard. Dr. Franklin was also a member of the central committee of Venceremos, a local organization that promoted armed self-defense and the overthrow of the government.

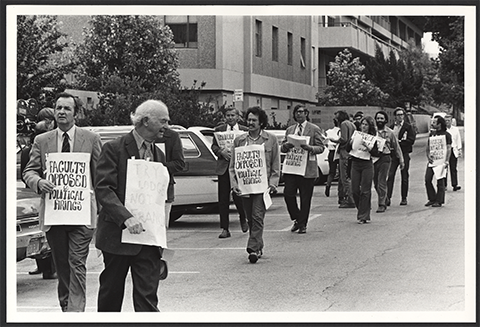

During campus unrest at Stanford in February 1971, Dr. Franklin urged students to shut down “that most obvious machine of war”: the Stanford Computation Center, which was thought to be engaged in war-related work. A crowd broke into the building and cut off power.

At the urging of the university’s president, Richard W. Lyman, a faculty board voted to fire him for inciting violence.

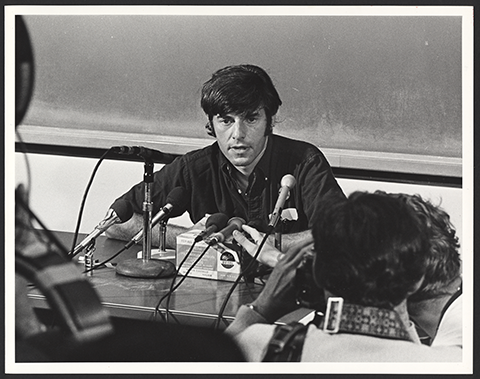

Dr. Franklin responded by defiantly holding a news conference with his wife, who brandished an unloaded M1 carbine rifle, meant to show “that’s where political power comes from,” he announced, a reference to a saying by Mao Zedong.

His dismissal was the first firing of a tenured professor at a major university since the McCarthy era, and it set off a national debate about academic freedom. Alan M. Dershowitz, then a young civil liberties lawyer spending a year at Stanford, argued that Dr. Franklin’s speech to students was protected by the First Amendment. The Nobel Prize-winning chemist Linus Pauling denounced what he called “a great blow to freedom of speech.”

The editorial board of The New York Times disagreed. “His conduct has been cowardly as well as irresponsible, manipulating students, endangering their own safety and damaging their future careers,” the Times editorial said. “It makes pawns of vulnerable young men and women, while the professor as instigator seeks immunity behind the shield of tenure.”

Dr. Franklin later sued Stanford, seeking back pay and reinstatement, but California courts upheld the university’s decision.

For three years, he was blacklisted — refused employment by “hundreds of colleges,” as he wrote in a memoir, “Crash Course: From the Good War to the Forever War,” published in 2018.

He was finally hired in 1975 by Rutgers University-Newark, where a decade later he was named the John Cotton Dana professor of English and American studies. He stayed at Rutgers until his retirement in 2016, publishing on a wide range of topics

Vietnam was a recurring theme. In 1992, in “M.I.A.: Or Mythmaking in America,” Dr. Franklin examined the widely held, and false, belief that U.S. soldiers were still being held prisoner in Indochina. It was a myth, he argued, spun up by Hollywood, in movies like “Rambo: First Blood Part II,” and by the Reagan administration, to forestall normalizing relations with Communist Vietnam.

“Still unwilling to come to grips with the origins and the terrible legacy of the Vietnam War, many Americans comfort themselves with legends,” Todd Gitlin wrote of Dr. Franklin’s book in The Times Book Review. “One reads his account wondering what is really missing in action in Vietnam.”

Dr. Franklin had a lifelong interest in science fiction, and he examined how its supposedly pulp themes were at the core of American culture. He wrote a book on the work of Robert A. Heinlein and another on how canonical 19th-century authors such as Poe and Hawthorne dabbled in science fiction. In 1992, he was a guest curator of an exhibition devoted to “Star Trek” at the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution.

Long after he was actively involved in radical politics, he became a saltwater angler off the New Jersey coast. His interest grew into a book about menhaden, a key fish in the coastal food chain, “The Most Important Fish in the Sea” (2007).

The book raised awareness of the commercial overfishing of menhaden for fertilizer and animal feed, which led the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission in 2012 to impose the first catch limits ever. The limits were credited with encouraging a rebound of menhaden along the Atlantic seaboard, and a return of whales, which feed on the fish, to New York Harbor.

Howard Bruce Franklin was born on Feb. 28, 1934, in Brooklyn, the only child of Robert Franklin, who held low-paying jobs on Wall Street, and Florence (Cohen) Franklin, who worked as a fashion illustrator for newspaper ads.

Bruce, as he was known, became the first in his family to go to college when he won a scholarship to Amherst. There, he felt estranged from his largely privileged fellow students. “I despised them from the top of their crew cuts to the soles of their white bucks, mostly hating the smug tweediness in between,” he once told a group of college teachers.

After graduating summa cum laude in 1955, he worked as a mate on tugboats in New York Harbor. In 1956, he married Jane Ferrebee Morgan, who had grown up on a tobacco farm in North Carolina and was working in the information department of the United Nations.

Dr. Franklin served for three years in the Air Force as a navigator and squadron intelligence officer in the Strategic Air Command.

He was accepted into the Ph.D. English program at Stanford, receiving his degree in 1961, and was hired as an assistant professor of English and American literature. His first book, “The Wake of the Gods: Melville’s Mythology,” was published in 1963 and remained in print for decades.

At the time, he thought of himself as a conventional Democrat. He volunteered on Lyndon B. Johnson’s 1964 presidential campaign.

But America’s growing involvement in Vietnam changed all that. In 1966, Dr. Franklin helped lead an unsuccessful campaign, which drew national attention, to shut a napalm plant on San Francisco Bay.

He identified as a revolutionary, a word that he defined, according to Time magazine, as “someone who believes that the rich people who run the country ought to be overthrown and that the poor and working people ought to run the country.” In 1972, the year he was fired by Stanford, he published “The Essential Stalin: Major Theoretical Writings, 1905-1952.”

In December of that year, he was arrested at his home in Menlo Park and charged with harboring a fugitive, Ronald Beaty, who had been serving a life sentence for robbery and kidnapping and fled when a member of Venceremos shot and killed an unarmed guard who was transporting him to court

In an interview that month with The Times, Dr. Franklin denied hiding Mr. Beaty but praised the violence that led to his escape.

“We believe that most of the people in prison shouldn’t be there, that robbing a bank is not a crime nor is having drugs,” he said. “And we believe those in prison should be freed by any means necessary.”

Several members of Venceremos were convicted of murder, but charges against Dr. Franklin were dropped.

“My father was able to prove he was not at the place that Ronald Beaty said he was,” his daughter Karen said.

In addition to Ms. Franklin, a forensic psychologist, Dr. Franklin is survived by another daughter, Gretchen Franklin, a criminal defense lawyer; a son, Robert, a physician; and six grandchildren. His wife, who wrote books about relations between Cuba and the U.S. and led educational tours to Cuba, died in 2023 after 67 years of marriage.

Karen Franklin said that she never asked her father whether he regretted his rhetoric about violently overthrowing the government. “I don’t think he considered himself a Maoist or a Stalinist any longer,” she said. “He was part of a movement that was national and international in the ’60s and ’70s. He was a leader in that movement; he was also carried along in that movement, and when the movement ended, his politics mellowed.”

Professor Dismissed After War Protests:

Howard Bruce Franklin, PhD ’61

If not for a failed eye test, Bruce Franklin might have been a fighter pilot. Instead, the man later known for his antiwar activities reported to his first Air Force squadron in 1956 as a navigator, thrilled to be flying in updated versions of the long-range bombers he had cheered as a child during World War II.

He would leave three years later, troubled by what he was coming to see as a dangerous and dysfunctional system of nuclear oversight. By the mid-’60s, he had become an emerging Melville scholar and was developing the concerns about the military’s escalations in Vietnam that would transform his life. In 1966, the Stanford associate professor of English led protests against the local production of napalm, an incendiary gel used in American bombs. Later that year, he and his wife, Jane, headed with their three kids to Stanford’s overseas campus in France, where encounters with Vietnamese refugees further radicalized their views.

When we came back to this country, we were Marxist Leninists, and we saw the need for a revolutionary force in the United States,

he told the New York Times Magazine in 1972.

The only tenured professor ever to be dismissed from Stanford, Howard Bruce Franklin, PhD ’61, died May 19 of corticobasal degeneration at his home in El Cerrito, Calif. He was 90.

Things boiled over in early 1971, when Franklin urged demonstrators to shut down Stanford’s Computation Center, which was reportedly running a government program related to the war effort. A crowd broke into the building and cut off power. The resulting discipline case, initiated by university president Richard Lyman, raised questions of academic freedom and its limits. A faculty hearing board voted 5–2 to dismiss Franklin, finding that he had incited the occupation of the center and urged defiance of police orders to disperse. (A third finding, that he had incited additional disruption during the violent night of protest on campus that followed, did not survive court challenge.)

Unable to find work in academia, he studied horticulture before getting hired in 1975 at the Newark branch of Rutgers University in New Jersey, where he taught until 2016. Not far from where he grew up in Brooklyn and teaching mostly working-class students of color, Franklin delighted in the change. Probably my firing at Stanford was good for me,

he told Stanford in 2021. I loved being at Rutgers.

He remained a prolific author on topics ranging from science fiction to prison literature to the legacy of the Vietnam War. After taking up saltwater fishing, in 2007 he published The Most Important Fish in the Sea: Menhaden and America, which is credited with inspiring marine protections along the Atlantic coast.

Franklin is survived by his daughters, Gretchen and Karen; his son, Robert; and six grandchildren. His wife of 67 years, Jane, also an author, died in 2023.

Marjorie Cohn

I'm sorry to hear this news, but it sounds like his passing was peaceful.

Bruce was a force of nature (and not without controversy). He was a teacher, a scholar and a revolutionary, with incredible energy. (but I never forgave him for giving me a B in his Utopia seminar).

Bruce and Jane were always very supportive of my work. Bruce inspired the collection "Reclaiming Judaism from Zionism," a significant book that I hope you all have a chance to read.

I wish your family much strength in the coming period as you mourn both of your incredible parents.

Janet Alexander

Deepest condolences to Karen, Gretchen, Robert and their families, and to all who loved him. Bruce was a friend, a mentor, and a hero to me. He was an inspiring leader and a brilliant scholar whose work had breathtaking range and depth. The Wake of the Gods is still the greatest academic work I've ever read and The Most Important Fish in the Sea was equally impressive in a completely different field and type of scholarship. He opened up not one but several new areas of academic scholarship, including prison literature and science fiction - not to slight his other significant works including his memoirs. In all things, his devotion to justice was paramount. May his memory be for a blessing.

Janet Alexander

Gerry Foote

Sending my love to the Franklins and I want to thank Janet for her message. Well said. Bruce and Jane affected my life deeply and taught me about the world upon which we try to have an impact. I may not have always agreed but admired them and valued their example in the struggle and life in general. Keeping all of you in my heart.

Gerry Foote

Franklin's Statement To Trustees

To: The Board of Trustees of Leland Stanford University and All Other Members of the Ruling Class of the Empire

"I have long been aware that my every appearance in public drew upon me the hostile attention of certain powerful persons in finance in San Francisco, and they redoubled their efforts to be rid of me. But I had no choice but to go straight ahead."

Professor Edward Ross (1900), the first in a long line of Stanford professors to be fined for their political views.

Thank you for your kind and generous permission to allow me to "comment in writing" on the decision of your management to fire me. You ask me to state my reasons why you should not "concur" in this decision, which of course you arrived at years before the events of early 1971, the subsequent charges, and the kangaroo hearing. There is no chance whatsoever that you will not concur, no matter what the facts were nor whatever I say now. But it may be important for all of us that the issues be spelled out clearly.

You should not concur for the following reasons: I did not do the things 1 was charged with. Even if I had, not one would violate either any law or any Stanford rule, written or unwritten. The university needs to have, and sooner or later will have, teachers saying the same thing that 1 did say in the political speeches now branded as "urging and inciting." By firing me you will merely further expose yourselves for what you are and Stanford University for what it is, and you will reap as you sow.

I. The facts

A. Urging and inciting. As people in the anti-war and anti-imperialist movement at Stanford are well aware, I have always maintained a policy of never advocating anything I would or could not do myself. In fact, I have always refrained from even voting in favor of anything I would or could not do, and hnve strongly urged everybody in public meetings to adopt this as a matter of principle. (Dennis Hayes can vouch for this.)

An examination of the four charges will show how grossly the Administration and the Board has misrepresented to you and the public the facts of this case.

B. The Lodge Incident. After a professor is unanimously acquitted of a charge brought by the Administration, and after it has been conclusively proven that the Administration's witnesses were presenting false testimony (including testimony by a member of the Administration), what would we expect from the Board serving as the judge and jury? Might they not discuss the seriousness of bringing false charges and warn of the dangers of political repression? Of course not. This Board reveals itself for what it is in these words: Franklin "describes the disruption at the Lodge speech as too weak, and clcarly indicates his own preference for more violent actions. This combination of views has the effect of making incitement almost a way of life." (p. 36) Where do they find this "preference for more violent actions"? They allude here to my letter to Lyman in response to the charge, a letter written ten days after the event. So here we have an example of ex post facto incitement. And what are the "violent actions" I prefer? What 1 said was this: "The appropriate response to war criminals is not heckling, but what was done to them at Nuremberg: they should be locked up or executed." So what the Board means by incitement is clear: Franklin's political views, freely expressed, constitute urging and inciting, no matter what the circumstances. Despite all their professions to the I contrary, this is precisely the standard they apply to the remaining three charges, which are all "urging and inciting."

C. The White Plaza speech. I did not urge and incite an occupation of the Computation Center. In fact I did not even mention it, nor did anyone else at the White Plaza rally.

Subsequent events prove the absurdity of this charge, if any proof were needed beyond the speech itself. During the hearing, uncontested evidence, produced by witnesses for both sides, proved that after the rally, the following happened: People went from the rally to the area outside the Computation Center. They stayed outside for 20-30 minutes. Somebody then entered, possibly by breaking in. Other people followed. They walked around inside and conversed with the people working there. After a while, some of the demonstrators said explcitly that there had been no discussion of occupying the building, that people had not thought they would get inside, and that therefore they should leave the building and hold a meeting to decide what to do. The great majority of demonstrators then left the building, and held a 40-minute meeting out front. It was at this meeting that they decided to go inside and stay there until Gamut-H, the S.R.I, amphibious invasion plan being programmed on the computer in direct violation of the university policy on research, was stopped. They made an uncontested decision not to do any damage and to make a public announcement that they were committed to this.

This is only one of many examples where the Board,in direct violation of Paragraph 15a, fails to include any "express findings upon all disputed matters of fact." To convict me of these ridiculous charges, they are forced to pretend that most of the evidence does not exist. Here and elsewhere, it is not a case of the Board choosing to believe one Administration witness and to disbelieve many defense witnesses. Rather they choose to deny or ignore the very existence of numerous defense witnesses as well as exculpatory evidence presented by Administration witnesses.

D. The third charge. Many hundreds of pages of testimony, hundred of photographs, and a video film all go to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that this is a false charge. What I did do was to attempt to get faculty observers to stay on the scene, and to attempt to convince the police not to attack the people. There is no other explanation of my behavior that makes any sense, as two of the Administration's key witnesses (Broholm and Moses) acknowledged under cross examination. As many witnesses, including several official faculty observers, attested, I put myself in physical jeopardy in order to try to prevent violence, the only violence that did in fact occur, the violence of the police against unarmed, peaceful, lawful demonstrators.

E. The Old Union speech. There was not a single witness on either side who testified that I urged and incited, or even mentioned, any unlawful, violent, or prohibited conduct in my speeches that night. The entire case here rests on an implied causal relation between these speeches and subsequent acts of violence. The Administration was permitted, over our repeated strenuous objections, to present evidence attempting to prove this causal relation. But when our turn came, we were not allowed by the Board to present our side of this key question. We did, however, make a formal offer of proof, which was noted by the Board. We offered to prove that the fight which occurred shortly after the rally broke up began when a group of right-wing students physically attacked, without provocation, a group of people who had been at the rally. We also offered to prove that the shooting which occurred later that evening was probably done by a member of the Santa Clara County Sheriffs Department. The Board's behavior here, neither allowing us to present our side of the case nor accepting as proven what we offered to show, outrages all notions of due process and judicial fairness.

II. Violations of what?

A. The law. If I did indeed urge and incite violent acts, this violates California Law. So I hereby urge and incite you to have this brought to criminal court, where we would at least be protected by subpoena, perjury laws, and legal precedent. But of course even the Administration has now quietly dropped its claims that anything I did or said was unlawful. There is now tacit acknowledgement that the First Amendment docs not apply at Stanford.

B. Stanford's rules, policies, and regulations, written and unwritten.

1. The Comp Center incident in relation to the speech in White Plaza. As we show clcarly in the final brief, the demonstration at the Comp. Center itself did not expose any participant to Stanford prosecution under the Policy on Campus Disruption or anything else. That is why none of the demonstrators was ever prosecuted by the SJC, although their identity was well known and proven in photographs. (In the one case that was brought, two people were acquitted of assaulting a photographer inside the Comp. Center. Their participation in the demonstration, which they freely admitted, was not at issue, and the SJC found no basis for prosecuting them for this.) So we have the strange case of someone being prosecuted for "urging and inciting" an action, which he never mentioned, and which, when it occurred, was not liable to University prosecution.

2. Outside the Comp. Center. Here the case is even clearer. The University Prosecutor himself stated flatly that a person who did refuse to disperse would be committing "no violation of any University regulation" and would not be subject to "any disciplinary action." (pp. 2645-2646). So even if I did what I have been falsely charged with doing I would be merely urging and inciting conduct which is permitted.

3. Here we have the ultimate absurdity. Not only are we not told what rules would be violated by conduct that I "urged and incited," we still do not know what conduct it is that I "urged and incited."

III. The penalty

There is no precedent for any of this. How then can firings be justified? Further, no warning was ever given, though I have been making speeches like this for years. You can't have it both ways. Either this is a first offense, which then would hardly justify firing, or else I have been doing the same thing before, without either prosecution or warning, and therefore was led to believe (as I did) that such speeches violated no rules. Of course I knew, as we all do, that such speeches and behavior (even speaking at movement rallies) were considered outrageous by you, the past and present Presidents, and most of the faculty, who hooted and booed me down when I attempted to present these ideas to them in an Academic Council meeting a few years ago. But there is supposed to be, according to your professed ideals, a vast difference between speeches that outrage established opinion and speeches that subject the speaker to punishment.

IV. Conclusion

But all of this is beside the main point. The essence of the case is that neither you nor your Administration nor the majority of the faculty you hire wish to permit a communist revolutionary to teach in your university, whose land you stole from native Americans and Mexicans, whose resources you stole from poor and working people, and which is financed, directly and indirectly, by money stolen from the working class at home and your victims around the world. You can not tolerate even one person expressing the views of poor and working people because such ideas do indeed, as the Board's decision states, threaten the very existence of your institution in its present form. But you cannot suppress our ideas by repressing us.

Sooner or later the people will take Stanford University away from you and will use all its vast resources to serve their needs rather than your sick drive for personal profit. In fact, they are going to take your entire empire away from you.

You are part of a dinosaur class, outwardly powerful and ferocious, but doomed by history because of the insatiable appetites and irrationality of your system. Go right ahead. Play your greedy roles to the hilt. And be remembered in history for what you arc by the hundred of millions of people you now rule but who will soon gain the power to control their own destinies.

It is you who will be dismissed, in every sense of that word. The poor and working people of your empire will win, no matter what you do.

In the Matter Of H. Bruce Franklin

The New York Times, Jan. 23, 1972

Due to its length, about 6,600 words, this article is reproduced on a separate page. Link

Daytime Dialogue, Renee Wedel Interviews Bruce Franklin on (MIA or Mythmaking in America)

About Books

Mention science-fiction to the uninitiated, and visions of extraterrestrial trivia come to mind. At least, that was the reaction of many academicians 22 years ago, when H. Bruce Franklin, now a professor of English at Rutgers University in Newark and a resident of Montclair, first announced that he would like to teach the subject.

These days, Dr. Franklin's classes are oversubscribed and his anthology, Future Perfect (Oxford University Press, revised, $8.95). not only enjoys perennial popularity, but also the esteem of critical circles for elevating the genre by demonstrating, as the author said, that literary greats like Hawthorne and Melville also wrote science-fiction.

Our century has become so transformed by change—technological, political and societal,

said Dr. Franklin, that, as seen in my latest book, Robert A. Heinlein: America as Science-Fiction (Oxford: $22.50; $6.95, paper), modern science-fiction keeps pushing closer to the core of our culture.

Nightmares of universal destruction, previously beyond our imagination, seem very possible now.

Heinlein has received the Eaton Award for science-fiction writing. At a two-day conference on science-fiction at Ramapo College in Mahwah this weekend, Dr. Franklin expects, he said, animated discussions because, to the residents of our heavily industrialized state, the destructive effects of a rampant technology—a dominant theme of science-fiction -seem very real.

H. Bruce Franklin

(1934-2024) US critic and academic, a cultural historian in various positions at Stanford University from 1961, in that year giving one of the earliest university courses in sf in the USA. In 1972, despite holding tenure, he was dismissed by Stanford for making speeches allegedly inciting students to riot against the university's involvement in the Vietnam War—a case well known to those interested in questions of academic freedom. He became full professor, again with tenure, at Rutgers University in 1975; continued as John Cotton Dana Professor of English and American Studies from 1987, and was appointed emeritus on his retirement in 2015.

Franklin is of some sf interest for his first book, The Wake of the Gods: Melville's Mythology (1963) (see Herman Melville), a study of the author's very far-flung sources. He is of direct sf interest for Robert A. Heinlein: America as Science Fiction (1980) and War Stars: The Superweapon and the American Imagination (1988; exp rev 2008). The former relates Robert A Heinlein's career to contemporary US history from a Marxist perspective, and won the Eaton Award for nonfiction. The latter is a pungent and important study about the US preoccupation with super-Weapons in fact and fiction, and how the two have interacted from the late nineteenth century until (as argued in the heavily revised second edition of the text) their inextricable marriage in the early years of the twenty-first century. The focus throughout is on sf tales which, tacitly or explicitly, anticipate the Holocaust of World War Three. Crash Course: From the Good War to the Forever War (2018) is both a memoir and a witty jeremiad about the future—including inevitable Future Wars—in store for America.

Of his two sf Anthologies, Future Perfect: American Science Fiction of the Nineteenth Century (anth 1966; rev 1968; exp and rev 1978; exp and rev 1995) remains properly influential for drawing attention to the sheer volume of nineteenth-century sf. A later anthology, Countdown to Midnight: Twelve Great Stories about Nuclear War (anth 1984), is a useful adumbration of his full presentation of the issue in War Stars.

Franklin published many other critical articles on sf and was among the genre's most respected commentators. He received the Pilgrim Award in 1983, and the IAFA Award as Distinguished Guest Scholar in 1990. He was a consulting editor of Science Fiction Studies from its inception until 2002. [PN/JC]

Professor H. Bruce Franklin WAR STARS

Books by H. Bruce Franklin

- The Wake of the Gods: Melville's Mythology (Stanford University Press, 1963)

- Future Perfect: American Science Fiction of the 19th Century (Oxford University Press, 1966; Revised and Expanded Edition, Rutgers University Press, 1995)

- From the Movement Toward Revolution (Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., 1971)

- The Essential Stalin: Major Theoretical Writings, 1905-52 (Anchor Books, 1972)

- Back Where You Came From: A Life in the Death of the Empire (Harper's Magazine Press, 1975)

- Robert A. Heinlein: America as Science Fiction (Oxford University Press, 1980)

- American Prisoners and Ex-prisoners, Their Writings: An Annotated Bibliography of Published Works, 1798-1981 (L. Hill, 1982)

- Countdown to Midnight: Twelve Great Stories about Nuclear War (DAW Books, 1984)

- Vietnam and America: A Documented History (co-author)(Grove/Atlantic, 1985)

- War Stars: The Superweapon in the American Imagination (Oxford University Press, 1988). Revised and Expanded Edition, University of Massachusetts Press, 2008.

- Prison Literature in America: The Victim as Criminal and Artist (Oxford University Press, 1978; Revised and expanded edition, 1989)

- M.I.A., or, Mythmaking in America, New York: Lawrence Hill and Co., 1992. Revised and expanded paperback edition, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-8135-2001-0

- The Vietnam War in American Stories, Songs, and Poems (Bedford/St. Martins, 1996)

- Prison Writing in 20th-Century America (Penguin, 1998)

- Vietnam & Other American Fantasies (University of Massachusetts Press, 2001)

- The Most Important Fish in the Sea: Menhaden and America[45] (Island Press/Shearwater Books, 2007)

- Star Trek and History (Chapter 6, Wiley, 2013)

- Crash Course: From the Good War to the Forever War (Rutgers University Press, 2018)

H. Bruce Franklin, Scholar Who Embraced Radical Politics, Dies at 90,

by Trip Gabriel, The New York Times, June 7, 2024. Link

Professor Dismissed After War Protests: Howard Bruce Franklin, PhD ’61.

By Sam Scott, Stanford Magazine, October, 2024. Link

Franklin’s Statement to the Trustees,

Bruce Franklin, The Stanford Daily, January 20, 1972. Link

In the Matter of H. Bruce Franklin,

by Kenneth Lamott, The New York Times, Jan. 23, 1972. Link

H. Bruce Franklin,

Wikipedia. Link

About Books,

by Shirley Horner, The New York Times, Oct. 17. 1982. Link

H. Bruce Franklin,

by Peter Nicholls and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, May 27, 2024. Link

H. Bruce Franklin,

Activism @ Stanford, Stanford Libraries. Link

Bruce Franklin, Rest in Power!

Green & Red pays tribute to a great radical scholar,” Green and Red Podcast, Hosted by Bob Buzzanco, YouTube, May 26, 2024. Link

Daytime Dialogue,

Renee Wedel Interviews Bruce Franklin on (MIA or Mythmaking in America),” Cloyes Archives, YouTube, June 1, 1992. Link

Professor H. Bruce Franklin WAR STARS,

YouTube, May 5, 2011. Link