April Third Movement

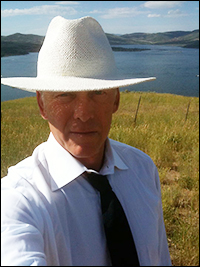

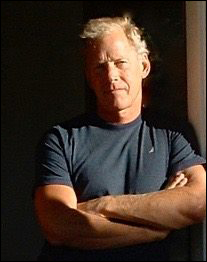

Irvin Arthur (Art) Busse III

Time has suddenly become of the essence

I’ve been waiting for the steady beat of natural and man-made disasters to slack off a bit before I ventured to talk with you about me.

I’ve been waiting for the steady beat of natural and man-made disasters to slack off a bit before I ventured to talk with you about me.

But the drum-beat, rather than slacking, has become a drum-roll instead. Disaster has become the new normal, with its lightning strikes hitting ever closer to home. Meanwhile months have gone by, and I really can’t wait any longer, as time has suddenly become of the essence.

If you were following along, you may recall that I was diagnosed with prostate cancer last November. After a hard look at the treatment options, I had my prostate removed in April. At first this looked to be successful — no lymph node involvement, clear margins etc.

The cheering was premature. Last Spring I discovered that the surgery had been too late. The cancer was out and about, looking for and finding new sites like a profit-crazed real estate developer.

My oncologist tells me I have stage 4 cancer, metastasized to the bones. She calls it ‘incurable’ with limited treatment options that, at best, are likely to delay my death by a few years, and which come with some nasty side-effects.

So that’s the headline — they say I’m going to die — a phrase that has been ricocheting around

inside my head and heart ever since I first heard it, remodeling my state of being like a wrecking crew.

Of course, the headline is where it begins, not where it ends. This will go on for a while, as I run through, and then possibly out of, treatments. If you like statistics, the mean range is five to seven years, but I’m expecting to land beyond that on the high side of the curve, given my vitality and genetics.

For now, I have no symptoms. In fact, strangely, just the opposite is true. I changed my diet and lifestyle after the surgery, started a regime of natural supplements, off-label pharmaceuticals, CBD/THC, and dropped 40 pounds. I haven’t felt so vital and healthy in decades, making for a daily, massive incongruence between what I’m hearing and how I’m feeling.

There have been many reactions, insights, and shifts in perspective in response to this news. In fact, it’s safe to say that EVERYTHING is changing. My first reaction was to fall in love with life all over again. I decided to make sure that the summer of ’17 was my best ever. It may have been. The rivers, valleys, mountains and lakes of the High Sierra held me like long lost lovers. Interesting, beautiful, kind people materialized out of nowhere like flowers after a spring rain. I found my myself at peace, more open and at ease, more likely to take pleasure in helping others, more appreciative of what’s already around me, and less likely to force the issue — any issue. I like all that. A lot.

Facing death as an aid to living always appealed to me, however I’ve been skeptical of the assertion that acceptance of impermanence would lead to joy. In the past, it never really sunk in beyond thinking about it, and the best I could do was work up a little bravado around dying.

Now, having no choice, I get it — down in my bones (literally and figuratively). I've been humbled, and without the silly bravado standing in the way, I am happy to report that I am full of joy and gratitude, that the world seems unbearably beautiful, and that my life has, indeed, been transfigured into an altar, just as Jeff Foster said it would in the quote below:

“You will lose everything. Your money, your power, your fame, your success, perhaps even your memories. Your looks will go. Loved ones will die. Your body will fall apart. Everything that seems permanent is impermanent and will be smashed. Experience will gradually, or not so gradually, strip away everything that it can strip away. Waking up means facing this reality with open eyes and no longer turning away.

“But right now, we stand on sacred and holy ground, for that which will be lost has not yet beenlost, and realizing this is the key to unspeakable joy. Whoever or whatever is in your life right now has not yet been taken away from you. This may sound trivial, obvious, like nothing, but really it is the key to everything, the why and how and wherefore of existence. Impermanence has already rendered everything and everyone around you so deeply holy and significant and worthy of your heartbreaking gratitude.

“Loss has already transfigured your life into an altar.”

—Jeff Foster

To have time between this transfiguring and the end is the greatest blessing of all. I look forward to every second of it. No doubt there will be suffering along the way — for us all — I hope yours is bearable and short-lived. For now, I am incredibly lucky to know what I know without it. Sharing my story with you, is actually me wanting to spread this wealth of wisdom around.

Merry Christmas, and Happy Holidays, beautiful people

Much love to all — Art

Love on the Downslope…

It’s been a year since I got the bad news — a year I could not have anticipated and certainly would never have asked for, but also a year full of unexpected grace and wisdom. Here, tonight, with St. Valentine on my shoulder and time running out, I’m thinking about Love.

It’s been a year since I got the bad news — a year I could not have anticipated and certainly would never have asked for, but also a year full of unexpected grace and wisdom. Here, tonight, with St. Valentine on my shoulder and time running out, I’m thinking about Love.

Which should surprise no one, least of all me. I’ve spent a lifetime in its thrall, set aside more conventional pursuits to answer its call, stalked and caught glimpses of the divine in the wild abandon of its embrace, filled endless Facebook posts with tales of victories and defeats, railed against the injustice of unrequited attention and praised it to the rafters when love’s beneficence poured down upon me.

But things have changed. It’s spitting distance to seventy from here. I was already getting older and beginning to fade, but before I could mount the campaign I had in mind to bolster my vitality and virility, I was cut short by a terminal diagnosis that drew a line in the sand separating then from now, my invincible youth, from my inevitable demise.

Strangely, the prospect of the last night spent wrapped around a lover, the last transfixing orgasm, the last erect phallus of a life-time penetrating the mysterious multi-dimensional realities of feminine space, has proven harder to deal with than the prospect of the last breath. And harder to talk about, too, leaving me to wonder why that is.

There’s an equation that expresses the relationship between these two variables in the algebra of prostate cancer; survival, no longer assured, might still be prolonged, but the price is potency. Sit alone in the woods weighing these things for a season, as I have, and you might be thinking what I’m thinking tonight.

That season in the woods was one of surrender. It came as a shock to realize I’d always believed, in a completely unexamined way, that I was immortal, and all the more so to find out that I wasn’t. It was with an unnerving mixture of panic and relief that I received this news. The big, long-term accomplishments — the unwritten novel, the new housing project in semi-communal small group living, the European residencies — whether under way or anticipated, were swept from the table with one call from my urologist.

But it was the smaller things that really got me, as I considered upon waking each day whether it was necessary to keep flossing, or change the oil in my car, or pay my taxes. Plus, I was suddenly free of and from judgement, as the platform from which to judge and be judged came apart and fell away into the abyss. I was free in a way that was novel, i.e., completely free, and when I wasn’t shaking in fear at the prospect, I was exhilarated by it.

Reasons for not doing things dissolved, but so did reasons for doing things. When looking back at my decisions from the perspective of eternity, nothing mattered anymore, and as meaning slipped away, beauty arose in its place and infused even the most mundane details of life with a shimmering effervescence. Love, with a capital ‘L’ arrived on the scene at long last, and redeemed me in the midst of my downfall.

This was not the kind of love I was used to. It was not about narrowing the focus from the field to the object, not about competing to acquire the object, not about getting from that object what it was I wanted. No, this was the kind of love that kept on filling me from within with a feeling of rightness, wholeness, and arrival that was its own reward. It showed me over and over again the interconnectedness of everything, and assured me of my place in the world. The hunter was being replaced by the gatherer, and the world that was once home to an anxious, scarce and elusive commodity, was becoming one of abundance where fields ripe with love surrounded me where ever I went.

Over the course of a year of diagnosis, prognosis, treatment decisions, and disease progression, as cancer had its way with me, so has Love, doing its work in increments. Clinging to hope at each stage delayed this transformation. Having that hope pried from my hands and heart accelerated it.

There was the usual disbelief, followed by the mobilization of resolve and marshaling of resources to meet the crisis. I started a regime of supplements and diet in the hopes of forestalling surgery, because surgery, I was told, would mean the likelihood of never having another erection, which I understood to mean never having another relationship, which, in turn, I understood to mean living without love — a fate I did not want to face. Instead, I did a ballsy dance with death for three months hoping that alternative treatments would save me. They didn’t, so I went ahead with the surgery and had my prostate removed. A few months went by before finding out that the surgery, which initially looked successful, had been too little and far too late.

The next line of defense was something called Androgen Deprivation Therapy — the administering of drugs that would block my body from producing the testosterone that this kind of cancer thrived on. In the criminal justice setting this is known as chemical castration and reserved for repeat sex offenders. The prospect of losing my libido, which I had been counting on to rally my surgical trauma-impaired erections, scared the hell out of me. Everything good about who I was and how I came at the world, possibly even my gender identity, felt to be on the line. I didn’t know who or what I’d be without testosterone and I didn’t want to find out. So, I doubled down on the supplements, added off-label pharmaceuticals, and a cannabis protocol with enough CBD/THC to render me unconscious for 14 hrs a night. Still, the cancer progressed. In the end, I kissed my manliness goodbye and went in for the shot in the ass that I expected would change everything.

I want to pause here because I’m having a moment in the re-telling of this story, and need to offer the man I was back then some compassion and empathy. It was a hard thing to do, and he did it bravely, without regret, without flinching. The man I am now feels for him, and wants to acknowledge his pain, and his strength. Of course, if I was still the man I was then, it would never occur to me to care, and should it have occurred, those feelings of empathy and compassion would have been casually drowned, like a sack full of unwanted kittens, in the pond of my own fear.

But I’m not the man I was then, and that’s the miraculous point of all this — I’m so much more.

The combination of looking death in the eye, while losing my false sense of invincibility and my testosterone, has landed me in a world that’s full of heart, with less to prove, and more to experience. When I stop trying to have my way with the world, which has become my new default, the love begins to flow. What a revelation to learn that everything I was terrified to lose, was exactly what had been blocking the path to everything I desired.

There’s a poignancy to it all now, and the tears that seem always so close at hand, are tears of joy. I’m more open and accepting and I’m more vulnerable, and that can be scary. I’m more at the mercy of the kind of people I used to be — aggressively pursuing their agendas, convinced of their purpose and their superiority, happy to demand and take what they want, oblivious to the damage done to others. I’m unwilling to don the armor and wield the weapons necessary to defeat them, so I walk away instead. It’s a small price to pay for a life overflowing with feeling.

It’s not lost on me that I have been experiencing something that many women might recognize as familiar. When I forget, there are the incessant hot flashes that come as a side-effect of treatment to remind me. Karma comes to mind.

It’s been months since my last unaided erection, although that may still change in time. I’m still in a relationship that began just after being diagnosed, as if the doctor had ordered it. She’s a saint-grade woman who means the world to me, and I am constantly amazed and grateful that, so far at least, she finds me worth the trouble.

It’s still possible that I may end my days alone. I hope not, but if that’s how it goes, it won’t be without love — it’s in me now, as well as all around.

Dancing Without a Partner

Here’s a newsy little post to catch you up on my whole end-of-the-world cancer situation.

Here’s a newsy little post to catch you up on my whole end-of-the-world cancer situation.

When you last heard from me it was Valentine’s Day and I was waxing literary on the subject of love on the downslope. That piece ended with something to the effect of me having a terrific relationship with a saint-grade woman who, at least for then, found me worth the trouble. Scratch that. Apparently I became more trouble than I was worth, because for the past four months I’ve been dancing without a partner, and trying to not come unglued about it.

In those same four months both of the standard treatments for advanced prostate cancer failed me as well.

Hormone deprivation therapy took away my testosterone, and a few other things with it, but not my cancer. So I did four cycles of chemotherapy.

That was interesting. But not much fun. I somehow avoided the typical physical side-effects such as nausea, exhaustion, hair loss, etc., but made up for it with a double shot of psycho-emotional effects. I could write a short story about those. Suffice it to say that it was like something between a bad in-law and the Angel of Death moving through me in slow motion on a cellular level. It would have been nice to not have been alone while going through that, but that was not my fate.

All the scans and numbers stopped their upward climb in response to the chemo, but neither did they recede. I was just buying time, and the time I was buying was not what one would call ‘quality’.

So I moved on.

I’ve found a new hope and a temporary home in Omaha Nebraska with the phase 3 Endocyte clinical trial of a promising new treatment. They like to give big trials catchy names. It’s a branding exercise that Big Pharmas can’t resist. My trial is called VISION, and its director is Alison Armour, whose name is actually not the result of a branding exercise.

The treatment features something like a hoodie-wearing terrorist with a backpack that’s got a neutron bomb in it. The terrorist knocks on the door of the local armory, is invited in, and his bomb goes off, taking out the armory but not the neighborhood.

To translate: a vehicle molecule — the terrorist — designed to be attracted to a protein that’s over expressed on the prostate cancer cell surface — the armory — but pretty much nowhere else in the body, is invited into the cell via the protein, while attached to the vehicle molecule is a beta-emitting radioactive isotope — the neutron bomb — with a short half-life and a limited irradiation radius.

Here’s a link to a more technical explanation for those of that mind:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5355374/

I’ll be going to Omaha — and that could be replaced with Albuquerque a little later — six times at six week intervals for a few days at each injection, starting in the middle of next month.

The good news is that I still have no symptoms to report, feel good, and have gained back much of the weight I lost along the way, since the diagnosis some two years ago.

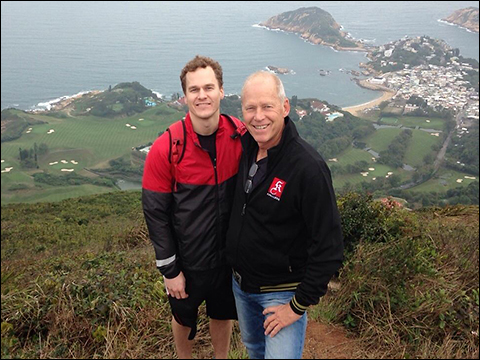

The other good news is that I’ve had a heartening show of support from many quarters for which I am most grateful. It’s been indispensable. Special thanks to my sons, Brian and Eric, my sisters Mary Ann and Bonnie, and my very special friends Chuck, Charlotte and Mel. What I used to look solely to my partner for, is now being provided by a wider circle of angels.

That’s it for now. Literature on the more esoteric fall-out from all this to follow from my ‘upstream’ writing retreat.

Love you all — Art

Bonnie Busse Pauli (Art's eldest sister)

Art Busse: October 30, 1948 – December 3, 2018

Art Busse: October 30, 1948 – December 3, 2018

Uniquely him self. Creative and loving to the core. Art passed away with his sons Brian and Eric by his side surrounded by many others of those he loved. Art reached to the sky for his last dance in the home he helped reshape among the mountains grass and animals he loved in the heart of Sonoma. A complicated man. His last days and the strength with which he continued to fight for a life he loved and the sons he did not want to leave confounded his doctors. The homes he designed, the Wonderful pictures he painted with words and the gusto and delight of his dance with life help us all to remember him.

With Art you usually knew where you stood but the prostate cancer that finally claimed him did not follow the expected course. To his family he was a bit of a rebel — going his own way and insisting on understanding life.

Born near his family home in Riverside, Illinois Art began swimming competitively with Dan O’Brien and the Riverside Golf Club. When the family moved to Winnetka he continued this phase of his life at New Trier with Dave Robertson. Art held three national high school high school swim records: 100 yd butterfly, 200 yd medley relay, 200 yard freestyle relay. His name was in the record books for several years. He was Illinois State champion In these events as well. Many of his team mates remain friends to this day. In particular he was very close to Chuck Goettsche whose support along with Charlotte Fuller’s and so many friends from California and Facebook meant so much to Art and his family.

Art had a well developed social conscience — so much so a professor at Princeton advised him to move to Stanford where it could be better utilized. Art was accepted to the honors program there - un heard of for a transfer, and was co founder of the SDS chapter. He received an honors degree in Social Thought and Institutions from Stanford University in 1971.

After college, Art first worked as a community organizer and later devoted his life to Building, History and Design based on movement and helping raise his boys, Brian and Eric. He began Busse Building in Oakland, CA and built several award winning designed homes and unique conceptual structures in the East Bay. His concept of circular Live-Work in Emeryville was way before his time. His website offers some great links to awards, designs, etc.:

Art enjoyed painting with words and he excelled at this endeavor which he worked on later in life. Some of these writings can be found on his website but many more on facebook.

Art’s influence on younger cousins, family, Facebook friends and so many in his dance of life will live on. We will miss you, Art.

Brian Busse

I’m not active on Facebook these days but my dad was. I’m also not much of a writer, but he sure was. He wasn’t a private guy rather really putting himself out there in the world. It feels appropriate to honor and grieve for him here.

This morning in California wine country with the fireplace lit, high ceilings, big windows overlooking a yard with frequent deer walking by my beloved father passed away. The porch was built by him and my brother, with a large iron ‘B’ for Busse hanging on the outside chimney. Both his parents, my grandparents, passed away in this house. With Family pictures and heirlooms sprinkled through the home, it was a beautiful place for his last days.

We are all in a state of shock. Time, our greatest enemy, took him too soon in a cruel, unexpected turn. The prostate cancer moving far faster that anyone anticipated. He was of strong body and mind. We were told years, only for the cancer to morph and take him in days/weeks.

Grateful I had much quality time with him in the preceding years and was able to be with him in his last lucid and interactive time, telling him how successful of a father and human being he was. Then sitting with him in his last days we took care of him, made sure he was pain free and comfortable and whispered our love in his ears.

Between many bouts of crying and darkness I’ve found strength in seeing the outpouring of support of family and friends from his different walks of life. It has been a testament to the force he was in this world, the presence he carried himself with. His legend will surely live on.

For anyone interested to get to know him better or see my insights on a truly great man the below is a eulogy I read to him while he was still with us, per his request:

I’d like to start with sharing a few of the ways the world likely saw my father:

- The Feeler. Hugs lasted 10 seconds at least. Looks that are into someone’s soul, not eyes, when conversing with them. Be it his lover, family member, friend, or Café Shop Barista. Life was too short to have surface level BS interactions.

- The Artist. Designing beautiful, unique homes and remodels. Writing in any form. Or just having the bottle of wine you’re sharing described back to you.

- The Hunk. The guy was good looking, let’s be honest. After a stressful work day he would come to my high school swim meet, park himself at the opposite end of the pool with his dress shirt off to get some sun and de-stress. Half the older girls on the team come to me with ‘your dad is SOOOO hot’. My only pitch was, better get me while you still can ladies, that’s me when I’m older.

- The Experimenter. At least that was what I yelled back at him when I was 13 years old, drunk off my face for the first time being told off. ‘It’s not fair, you experimented when you were young too!’ Think I played that card some years too early. Would have been good to have in my pocked for use closer to 18 and messing up.

Next I’d like to share how his oldest son saw him:

- The Parent. Loved him and liked being around him in my childhood years but was truly scared of crossing him and being on his bad side. The yell stronger than a lion’s roar you never wanted to hear. Wasn’t him losing his temper so much as a strategic ‘fear of god’ moment to snap you straight. I quickly learned when to drop an argument and make sure my homework was done. Come to think of it his building suppliers would also learn quickly when to make sure they stopped delaying a furnace or door delivery in similar fashion. I always felt protected by his strength and calm confidence though and new the world would never cave around me with such a person looking after me.

- The Best Friend. At some point, around early college years he made the switch from parent in the traditional sense of the word, to more advisor and best friend. The angry roars were gone and a calm, reassuring voice of a friend who has your best interests in heart took its place. He’d been through most anything I was going through so why not use him as a resource was how he saw it. I really admired that about him as it seemed a much more enjoyable way to interact with your adult kids. As cliché as it sounds I knew that if I couldn’t tell my dad about something in my life than I really shouldn’t be doing it, and have used it as a barometer for my actions to this day.

With that said my greatest fear in life after my own death has now been realized. Pops you were my best friend. A bond and love so deep I am terrified to live without it. Your presence will continue to guide me as I strive to be a better man. I will show my family the strength and confidence you showed us, reassuring them someone will always be there. Until we meet again, I love you dad.

Eric Busse

Today I'm here to honor my father's life, but most importantly his love of life.

Growing up, I thought my dad was just the coolest most badass guy in the world. I remember being in the 5th grade and everyone was talking about Arnold Schwarzenegger bc of terminator 2. I told all my friends that my dad could easily beat him up. Let's just say I got laughed at quite a bit for a long time. I didn't care, because in my mind and in my heart I knew he could. Even to this day I know he could!

My dad has always been this superhero type of guy to me. He’s strong, hardworking, ruggedly handsome, and lives his life with a high set of morals. What's right and what's wrong was always made very clear to me. I just choose not to listen a lot of the time.

Today I'm here to honor my father's life, but most importantly his love of life.

Growing up, I thought my dad was just the coolest most badass guy in the world. I remember being in the 5th grade and everyone was talking about Arnold Schwarzenegger bc of terminator 2. I told all my friends that my dad could easily beat him up. Let's just say I got laughed at quite a bit for a long time. I didn't care, because in my mind and in my heart I knew he could. Even to this day I know he could!

My dad has always been this superhero type of guy to me. He’s strong, hardworking, ruggedly handsome, and lives his life with a high set of morals. What's right and what's wrong was always made very clear to me. I just choose not to listen a lot of the time.

One of the things I admire most about my dad is how he handles tough situations. It seems the more intense and the more stressful a situation gets the calmer and more collected he gets. He’s one cool customer. It’s really an amazing thing to watch. The older I got the closer I became to my dad. He turned from not only my father but to my best friend. When the 3 Busse men get together it was always full of love and lots of laughter. Most people don’t like to spend time with their parents but that's far from the case with me. I love spending time with my dad. We would go hiking, go work out together, and go on these great trips to butterfly grove, the Yuba River, Tahoe, and Park City, Utah. What we also shared was a passion for film. Granted I don’t walk out of 65% of the movies I go and see like he would do.

I remember seeing a movie with Sean Penn about 3 to 4 years ago called ‘The Gunman’! I loved it, and I looked over in excitement to see if he was experiencing the same joy I was feeling. I delightfully witnessed a smile on his face that made him look like a 7 year old after he got the best candy haul on Halloween night. It was utter joy. A smile from ear to ear. What a movie that was! We started a slow clap at the end. People followed as they usually do with dad. I loved that day.

Sadly my story in life has been full of a lot of hardships. I have been battling a disease that has taken me from highest of highs to the lowest of lows. It's a terrible thing to put your family through addiction. I've done things that I'm thoroughly disgusted with. Things that I would never do in my right mind. That's the disease of addiction though. But no matter what I did or how bad it got my dad has always been there for me. Picking me up from the gutters guiding me back to the light. Through his love, I started to fight. I can't do this to him or the rest of my family anymore, I would tell myself. Thankfully Life has found its spark again. What was once black and white is now illuminated with the brightest of colors. I am now truly starting to live.

Thanks to my dad. He showed me life is too beautiful and there is too much love in this world to waste on being consumed by a false high. An unnatural high. The high of friendship, spending time with family, and finding love - now that's a high that feels better than anything any drug can ever make me feel. This is what my dad showed me.

I love you dad. You have always believed in me. Always been there for me. Always loved me. Even when I couldn't even love myself. Thank you for everything you have done for me Dad. I am the luckiest son in the world to be able to call Irvin Arthur Busse, III my father.

Phil Trounstine

Art and I met in September 1968 at Stanford when both of us were looking for housing. We became instant friends, roommates and comrades — a relationship that we kept alive in our hearts for 50 years. Art had a brilliant mind and an expansive heart. He was an explorer of all things, unafraid of change, committed to decency and a delight to spend time with. He had the great facility to be deadly serious about things that demanded it and at the same time not take himself or his latest fancy too seriously. He fell in love more times than any man I’ve ever known. And women adored him. Art was a swimmer, dancer and lover. But for me he was, most of all, a constant friend and brother. He would be delighted to know that we all remember him as a truly human being. I miss him already.

Phil Trounstine

Art Eisenson

Art Busse was one of those people who validated our sense that we were doing something right and decent because he was with us.

Art Eisenson

Janet Alexander

Art was charismatic, brave, sunny, smart, and good-hearted. He was the instigator of a street theater bit we did one Parent's Day at a program outside behind Tresidder. About 5 of us, trooped up to the front, looking normal. The parents thought we were part of the program and I guess the responsible adults thought we were cute or thought it would look bad to try to wrestle kids away. We started with some little speech like, "We are the best of the best, the cream of America's crop." Then we whipped out our helmets from behind our backs and said, "We are the people you warned us about." It was fabulous. When we went to SRI, he looked out for all the less experienced people. I remember him at the free concerts at Lytton Plaza.

Art was funny, and loyal. He was imaginative and an artist at heart. I remember when he got his general contractor's license and started a business of renovating and selling houses with Charlie White and Rick Stewart. Though I lost touch with him after I moved away from Mountain View, I was not at all surprised when I Googled him and learned that he had gone on to become a daring postmodern architect.

Very sad to hear he is gone.

Janet Alexander

Marc Weiss

I briefly shared a house with Art (and many other SDSers) for a few months on Lawrence Court in Palo Alto during the spring of 1969 when we were all suspended for the quarter as members of "the Stanford 29." It makes me very sad to know that his smiling face and enthusiastic energy will no longer be gracing our world (except in photos and videos, such as your 1970 poster and the 1969 PBS film).

Marc Weiss

Jane and Bruce Franklin

We remember Art as someone who carried explosive energy with him wherever he went. A dynamo of creativity. His son's words are a serious tribute, and we send our warmest thoughts to Eric and the family and the friends who were with Art in the end.

Love, Jane and Bruce

Jim Shoch

I knew Art well in those days. As people have said, he was in the thick of everything at Stanford in the late 60s. His intelligence and magnetic personality were a big reason those times were so exciting.

Art and I actually grew up in the same town north of Chicago, Glencoe, and went to the same high school, mighty New Trier, although I didn't know him then. At Stanford we lived in two houses together on Lawrence Court and Montrose Street in Palo Alto along at various times with Larry Christiani, Barbara Lee (I think), Bob Abshire, Terry Karl, Vic Congleton, Marc Weiss, Sandy Kroopf, and possibly others. We also staged a number of guerrilla theater actions together the most notable of which as I recall involved a group of us (also including Larry, Barbara, and Guy Smythe) getting royally stoned, making some cardboard airplane costumes labeled with the names of corps Stanford trustees were affiliated with, and then heading over to Roble Hall where Ken Pitzer was having dinner. We then bombed and strafed Guy dressed as a Vietnamese peasant with cardboard napalm bombs and pea shooters. A dead

Guy picked himself off the floor and flipped over his Vietnamese peasant

sign to display another asking, Do you know how your trustees make their livings?

There was also a group trip to Big Sur (also including, I think, Liz Wiltsee, David Pugh, Lucy Wieland, George Reinhardt, Johnny Gostovich, and others) where Don Lenzer and Michael Nolan's PBS crew filmed us romping on the beach for a scene in the notorious Fathers and Sons.

After a run-in with the law that I won't discuss further, Art and I took a trip up to Portland for the RU to scout out expansion possibilities for the organization there. That trip and the contacts we made probably contributed to Art's decision to move to Portland that he describes in his bracing memoir.

I only saw him occasionally after that. But he obviously went on to live an astonishing, accomplished, and eventful life. He'll be missed.

Jim Shoch

Re: Jim’s mention of Big Sur

I think he’s referring to the time when SDS sponsored a hitchhiking race from the Quad to Pfeiffer State Park. Art and I were partners and, if memory serves, we won. What I know for sure is that a lot of young women stopped to give us rides which, I attribute, to my tall, handsome partner.

Phil Trounstine

Dave Pugh

I have learned a great deal about Art’s post-Stanford life, especially from his son and from the piece that Art wrote a while ago.

I can add that Art and I joined SDS at the same time, around the fall of 1967. Art was part of the undergraduate “core” of SDS. He had a strong sense of the questions that students in the dorms had about the nature of the war and whether the classified research that Stanford professors were doing for the Defense Department could be justified. Art also had a wicked and merry sense of humor that leavened SDS’s seriousness.

Dave Pugh

Anne Bauer

Art could make his life sound unbelievably adventurous. Larger than life perhaps? I wish I had known him better. I remember having the same feeling running into him at one of our A3M reunions. A life thoroughly lived. Bill Black reminded me of when we had shared a house with Art and others in Menlo Park in 1969. Guess what happened that year?

Anne Bauer

Stranger at the Door

With the death of Neil Armstrong on August 25 the media was flooded with commentary and pronouncement about the first manned moon landing of the Apollo 11 mission on July 20, 1969. Everyone agreed on its significance as a pinnacle of human success—the ultimate ‘A’ on our collective report card. As the official White House statement put it: “when Neil stepped foot on the surface of the moon for the first time, he delivered a moment of human achievement that will never be forgotten.”

With the death of Neil Armstrong on August 25 the media was flooded with commentary and pronouncement about the first manned moon landing of the Apollo 11 mission on July 20, 1969. Everyone agreed on its significance as a pinnacle of human success—the ultimate ‘A’ on our collective report card. As the official White House statement put it: “when Neil stepped foot on the surface of the moon for the first time, he delivered a moment of human achievement that will never be forgotten.”

I’m not so sure. I think something far more profound happened that day, forever changing our feelings for each other and what it means to be human.

It was the summer of 1969. Things were different back then, but in some ways not so different fromtoday. Change was in the air. Some were rushing to embrace it, others were digging in to stop it. On break from college, I was hitchhiking home to Chicago from the East Coast and got a ride that morning in western Pennsylvania. The driver was white, working class, a little older than I was, and between jobs. I think he was a Vietnam veteran. We passed the time trading stories and working the radio dial. A few hours into the drive, the music was interrupted by an announcement. History was calling—the Apollo moon landing was about to be televised. I turned to the stranger behind the wheel and said with absolute earnestness, “Listen, man, we have to see this thing happen. We can’t not see it.”

He agreed, but what to do? We were in Eastern Ohio by now, deep into the rural Midwest. The first thing was to get off the toll road. I figured we’d drive into the nearest small town and find a bar with a TV. The town we found was small alright—I don’t even remember its name. But we couldn’t find an open bar, and time was running out as we careened down potted streets past rows of run-down bungalows. “Five minutes until touch down,” the radio announcer intoned. “Pull over!” I shouted, preparing myself for what I’d decided was our only hope. As the car lurched to a stop I jumped out, ran up to the nearest house and pounded on the front door. It swung open immediately, as if we’d been expected, and just beyond the man of the house, I could see the rest of the extended family, and maybe a neighbor or two. They were all pulled up around the TV watching intently. None of them even turned their heads to see what the commotion was. I focused on the man in front of me and said, “Look, I know you don’t know me—hey, I don’t even know that guy out there in the car I just pulled up in, but in a minute they’re going to land on the moon, and we’ve got to see it. Please, please let us watch with you.” He didn’t even think about it. He just stepped back, swung the door open a little wider, and said, “Get in here.”

We pulled up a couple footstools and took our place in the crowded room. The screen was small but we had no problem sensing the significance of what was happening. We could feel the families in the other living rooms of that town drawn up in silence and awe around their TV sets. We felt them doing the same in the small towns of the surrounding countryside, in the cities and suburbs across the Midwest and out to both coasts, over the oceans and around the world. The world was watching as we were, eyes on the TV image or turned skyward, ears leaning into radios, no one breathing, just suspended in the magic of the moment.

And then, with an awkward little hop the first human foot landed in the lunar dust, sending a poof of it into the nearly weightless air, and the words were spoken and heard by an expectant world through the crackling static of great distance: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” What happened with the sound of those words was a strange thing indeed. It was as if something came out of the TV and washed over everyone there in the room and continued on through the opposite wall and out over the town and around the world, and then a few seconds later, after circling the globe, I swear we could feel it come back again, through the other wall, exalting us. It was like a wave of kinship that had flooded the world, turning a planet full of strangers into a single family where the only bond that mattered was the one shared by all—we were the inhabitants of planet Earth.

And so, for the first time we earth dwellers became aware of the totality of human existence; life, not in its endless variety and ever-expanding confusion, but life as a global phenomena contained on the surface of a sphere, a tiny spec of blue-green swirl in the endless inky void of infinite space, with only the thinnest envelope of vaporous atmosphere standing between warm life and frozen extinction. How unimaginably precious, terrifyingly precarious, and shockingly absurd it was to think that there might as easily have been nothing. Is it any wonder that as Armstrong looked back from the moon and spoke to the rest of us here on Earth, there was a shuddering disturbance in the collective field of human consciousness?

There was a huddling then, a shifting of the props on the stage set of life as the differences we’d placed so carefully between us fell away. What was strange became familiar, and we all moved a little closer together.

It’s been over four decades since the moon landing, and what started as a communal feeling and a shifting perspective has become the agreed-upon facts-on-the-ground of our time. The end of the Cold War, the advent of globalization, the consolidation of worldwide agricultural, commodity, and financial markets, and the rise of the Internet and satellite communication have indeed produced the so-called global village Canadian philosopher Marshall McCluhan predicted back in the 1960s.

That’s not to say it’s been easy. There’s been a lot of kicking and screaming along the way, and the change is far from over. As with all families, the assimilation of the in-laws is generating plenty of friction. But for better or for worse, there’s no going back. We’re family now, and perhaps we can thank our unassuming Uncle Neil for that.

Tracks in the Snow…

What traces have I left behind so far on the trajectory of my adult life? A series of seven year monogamous relationships, two formidable sons, a handful of amazing houses, some worn out flamenco boots, a pump station in the Alaskan Mountain Range, way too many speeding tickets, and an FBI file that's bigger than yours.

What traces have I left behind so far on the trajectory of my adult life? A series of seven year monogamous relationships, two formidable sons, a handful of amazing houses, some worn out flamenco boots, a pump station in the Alaskan Mountain Range, way too many speeding tickets, and an FBI file that's bigger than yours.

But these are mere artifacts, tracks in the snow of what has been a great expedition. They’ll be gone soon enough, and they don’t really tell the tale. The quality of the experience, what I've learned about myself and the world, the ways I've changed, and the ways I've changed others through their experience of me speak more fully of what my life has been. Some of the most rewarding things I've done and been don't have a shape to point to; they've taken place within me, or in the hum of the air between me and another.

My story after Stanford radicalism goes like this: I considered law school for about twenty minutes, admiring the work of Charles Garry, and William Kunstler, high profile left-wing defense attorneys doing their best to shield the Black Panthers and other activists from the repressive onslaught of the State. But I decided I'd rather be one of the guys I'd be defending had I done so. I also thought about going up to the country, homesteading somewhere remote and saying ‘to hell with politics’. I sent away for maps of the tracts of federally owned land that was available to be homesteaded and overlaid them with maps showing seasonal meteorological conditions trying to find the ideal location.

I compromised, and packed my pick-up, took my dog and my shotgun and moved to Portland, Oregon where I recruited some locals and started up a collective affiliated with a Bay Area Marxist-Leninist organization coming out of the student movement. I worked in furniture factories, organized in my working class neighborhood, and just generally caused trouble for the ruling class and anyone else who wanted to have a nice day without addressing how screwed up things were. After a year or so of this and under the influence of other ex-student radicals who were taking things too far, like the Weather Underground, I thought it would be a good idea to create a false identity and kite checks all over town to raise much needed supplies for Portland’s various revolutionary organizations. That led in short order to a secret grand jury indictment, which I was able to find about from sympathetic comrades in the district attorney’s office in time to high-tail it out of the state, but not before shacking up with a comrade in Eugene who liked me well enough to join me in my flight from the Law. We moved to Chicago, got jobs in factories and watched as the movement split into a million pieces and died, leaving us on our assembly lines without a cause beyond the weekly paychecks.

About that time the law caught up with me and I got thrown in a one room jail in western Illinois where I was an instant criminal celebrity, having made the FBI’s fugitive list. I shared the cell with a handful of locals and every night the sheriff would send out to the diner across the street for our dinners. I was extradited back to Oregon in cuffs on a commercial airliner, further cementing my celebrity status, and ended up doing time in ‘Rocky Butte’, the Multnomah county jail. From there I went to the work release center where they let me out during the days to work construction.

One of the terms of my probation was to get my Stanford degree. I had left Palo Alto one dissertation short of a diploma. So I wrote about my experiences as a revolutionary labor organizer, snagged my degree and moved back to Chicago and first the factories, then high-rise construction projects. During the days I’d try to talk those working beside me into my idea of socialist revolution, but every night I'd have the same dream. You know that place at the south end of San Francisco where Highway One drops down a big hill into Pacifica and you can look way down the coast into the sun and sparkling waters? Well in this dream I'd be hovering over that spot like a hawk in the wind and there would be this song playing

Seventy-three men sailed up from the San Francisco Bay

Rolled off of their ship, and here's what they had to say

"We're callin' everyone to ride along to another shore

We can laugh our lives away and be free once more"

But no one heard them callin', no one came at all

'Cause they were too busy watchin' those old raindrops fall

As a storm was blowin' out on the peaceful sea

Seventy-three men sailed off into history

Ride, captain ride upon your mystery ship

Be amazed at the friends you have here on your trip

Ride captain ride upon your mystery ship

On your way to a world that others might have missed

It was the ‘we could laugh our lives away and be free once more’ line that really got me. I'd wake up with my pillow soaked in tears, get up and punch that God damn time clock again. After a few months I finally got the message and moved back to California, this time to east Oakland and more construction work, laying water mains in Contra Costa County, and building concrete parking garages, hospital wings and civic structures all around the Bay. It was the mid seventies now and with my relationship about to self-destruct, I got wind of work on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline and took off for Fairbanks, which by then was a total boom-town, having doubled its population overnight. It was a blast. This old frontier town still had signs up outside the bars on Second Street instructing patrons to leave their guns and knives with the bartender – most of the patrons complied. Every other person you met was an adventurer/soldier of fortune type or a camp follower. The rest had been nuts enough to move there in the first place before the boom. I made many friends from many walks of life. We all had nick names, and too much time on our hands as we waited for our numbers to come up at the hiring hall. On top of that it was summer and the sun never set. The stories go on and on. Eventually I got out on a job building Pump Station number 10 in the Alaskan Mountain Range. I worked 8 weeks, 7 days a week, 10 hours a day until the first snow and then came back again the next summer to work setting feeder lines from the well heads on the North Slope to where the main line started above the Arctic Circle in Prudhoe Bay on the Arctic Ocean. More stories.

From there it was back to Oakland, a contractor's license, buying old houses, fixing and selling them. Then into remodeling and adding on to other people’s homes, and a wife and two kids. I had been moping around for years complaining to myself about how boring and meaningless life seemed on the small scale as the establishment mopped up the remnants of the counterculture, turning the things I valued most into commodities and me and my friends into consumers. The Sixties went all the way out to sea, and I was about this close to becoming fully jaded when my first son popped out into my arms at three in the morning on the bathroom floor of our little bungalow on the Piedmont-Oakland border, and cracked open my hardening heart. Suddenly I was crying at movies again.

Along with the twanging heartstrings came the panic. 'Holy shit, I've got mouths to feed, a family that is depending on me'. I'd been working construction as a lesser of evils while waiting for something meaningful to come along, but meaning would have to wait now that I had kids. I got serious about work and started turning an occupation into a business. My wife, another radical from Stanford, the first woman to climb a phone pole for Pacific Bell, and one of the first female marathon runners, worked as a court reporter. Together we were making a life for ourselves when disaster struck.

Coming back from our summer vacation in the Sierras, my wife, her mother, the kids (4 yrs, and 4 months old), and the family dog were all in the station wagon. I went on ahead with the pickup full of our gear. I made it home. They didn't. A freak downpour flooded the freeway and sent the car hydroplaning off a curve and down a steep embankment where it struck a tree. My wife suffered a traumatic head injury that put her in a coma her doctors thought she wouldn't survive. The others sustained various minor physical injuries and major emotional ones. Our carefully planned life was tossed in the air like so much salad.

We had been living on my wife’s salary while I took off from my paying jobs to design and build our new family home. It was half done when the accident happened. I had to go back to work, double my income, finish building our home, raise two kids and make daily trips to the intensive care unit in Sacramento where my wife struggled for her life. Along with our families, a brigade of friends we didn't even know we had turned out and held us up through it all. My wife defied medical expectations and made it, although seriously and permanently disabled. So did our children. So did I. We separated not long after her return from the hospital, but I stayed close, a few blocks at most, as the kids went back and forth between households throughout their school years.

Meanwhile back at work: it was the red hot end of the eighties and I tooled up into it with a vengeance, a warehouse, an office and staff, a half dozen trucks, forty employees, and a big credit line. The Boomers were breeding and everybody had to have a second story addition, or a new kitchen and backyard deck now! I got hot undergraduate co-eds from U C Berkeley to drive the fleet of little red trucks with my name on them around town ensuring the best service and lowest prices at the lumber yards as well as top-level morale at our job sites. I hired multi-talented, vastly over-educated artistic and intellectual types with good people skills who thought construction was fun as my job site supervisors. I went at building the company like a utopian socialist experiment, trying to provide a place where my ‘co-workers’ could earn a living without suffering the alienation we Marxists spent so much time worrying about. Considering it was work, and a lot of it hard work, we had a very good time, and along with serving our customers, we entertained, educated and mystified them, earning honorary favored uncle and aunt status in their families and invitations to their holiday gatherings. The competition grumbled about our legendary customer satisfaction and employee loyalty but was powerless to stop us.

But all good things must come to an end and one day in the fall of 1990 the phone stopped ringing. The next day the only call we got was from the bank notifying me that they were calling our credit line. ‘Don't feel bad’, they said, ‘We're pulling credit lines on all our contractors’. It was official, the real estate boom of the late 80s was over, and with it residential remodeling. Our top heavy, utopian enterprise sank like the Titanic, its race to the bottom slowed only by the Oakland Hills fire a year later. I filed for Bankruptcy in 1994; the same year I left my live-in lover, breaking up our oh-so nineties complicatedly blended family arrangement.

All was lost, but with the loss came freedom. I had been secretly miserable as a businessman, and the responsibility that came with keeping forty people employed when added to caring for my children and disabled ex-wife was robbing me of my ability to enjoy life, and alienating me from my own feelings, needs and desires. I rose out of the wreckage a new man dedicated to living through his feelings, and expressing himself and his truth through Art. I learned to assuage the pain of loss with the salve of Flamenco and in the process met and married my Flamenco teacher. With this new orientation life got exotic in a hurry.

The paraphernalia of commerce was gone — the trucks, the warehouse, the employees, the clients. Using other people’s money, I bought three inspiring view lots high in the Oakland Hills at the bottom of the market, and used them as playgrounds for my creative spirit, designing and building homes. Then three more and three more again in other parts of the hills all with fabulous views of the Bay and it's bridges.

Meanwhile, at the bottom of my own emotional market, I dragged my sorry ass to a beginning flamenco dance class determined to experience the pain of my loss more fully while finding the pride to stand tall through it all. Somehow I knew the first time I heard the music that it was about pride and pain, and understood instinctively what was being conveyed in every syllable of the lyrics despite their being sung in a language with which I was completely unfamiliar. It's the musical form of the Gypsies who migrated to Spain. Tribal, nomadic, pre-literate, dispersed around the world and persecuted wherever they go, the Gypsies have a tale to tell, a song to sing, a dance to dance, and it's in the telling and the singing and the dancing that who they are as a people resides — where they come from, what they've endured, how they feel. But the strangest thing is that somehow, inexplicably, I discovered that in its purest form, all that resided in me as well. That in my heart I was a Gypsy.

I had a dream where I was traveling in Spain. Just a typical American tourist. I'd gotten off the beaten path and was hiking on a trail in remote mountain country. The trail brought me to a small village where I encountered an old woman doing her laundry in the fountain at the center of town. She looked up at me and her expression changed from indifference to one of shocked recognition. She ran to me and on her knees in the dust took my hands and said through her tears "Oh my God, you've come, you've come, just as they said you would." As she spoke the words I recognized in myself what she saw in me and became in that moment who I had always been but never acknowledged myself to be — the King of the Gypsies. I set up a table in the plaza and started settling arguments, marrying couples, dispensing justice and wisdom, and receiving money and respect. I knew exactly what to do relying solely on my instincts and feelings. I stayed in that village and never looked back. I awoke to a bed soaked in tears, and a new identity.

That first flamenco dance class was taught by a woman named Marina, and along with being my teacher, she became my portal into a new world, and after a determined courtship spanning two years and several states, my wife. She deserves a book of her own. Her mother was a white Russian countess fluent in eight languages, a triple Libra, and an emotionally damaged little girl whose sheltered existence shattered one night when they came for her father and executed him. Marina's uncle, the Count, lived the classic life of the expatriated Russian nobility in Paris, impoverished but absolutely convinced of his superiority to everyone he looked out upon. Her father was a shrewd Dutch intellectual who made his way after the war by putting the finger on hidden Nazi war criminals for the military intelligence branch of the American occupying force, which he parlayed into American citizenship for his family. They immigrated when Marina was two, settling in Nowheresville, New Mexico where she spent her childhood years staring at the sky and training grasshoppers.

She was special — a beautiful gem with flashing facets and razor sharp edges. She had a way of carrying herself that earned her either followers or detractors at the first glance. Just the way she stood was epic. In motion, she was as definitive as an act of war. So totally true to herself that every move she made was the only one she could possibly have made. She was a stunning modern dancer and an even more talented choreographer, who got mugged by flamenco in much the same way as I had. She had little use for the rest of the world except to teach it what it so obviously needed to know. She was a class act and, as you might already have gathered, a handful.

From the first time we met, nothing was ever the same — literally. Normal went over the hill and was never heard from again. Things never played out according to expectation. It was a brave new world that was the way it was each day because of how we made it as we went along. Life became a stage set infused with drama and artistic craft. We were artists, fated to be mated, and the salons formed up around us wherever we went as if following laws of nature.

I started hanging with a whole new crowd. Marina's people, mostly. These were the dancers, the choreographers, the painters, the actors, the poets, the intellectuals, the misfits, the weirdos, and the divas (oh my god, the divas). They were all so colorful, so personal, so inspiring, so neurotic and delusional, and so broke. Every one of them a one-of-a-kind. I'd go to parties in someone's little North Oakland or Berkeley bungalow populated with these folks and they'd have such large personalities overflowing with imperatives, superlatives, screwy notions and big ideas that even a handful made the room feel vibrant and crowded. I totally loved it. What a relief from the bedroom community parent set I had been hanging with.

When we married, I had promised to get her back to New Mexico one day, and one day I did. We moved to a house in Corrales, an old ranching town between Albuquerque and Santa Fe on the banks of the Rio Grande. I kept working in the Oakland Hills, living in a trailer on one of my lots when there, and commuting to our new home in New Mexico every couple of weeks.

She danced and taught. I danced and designed and built. Each house was a little freer, a little more original, a little truer to something that was hard to describe. The land spoke to me, or rather to my body, sending it into motion producing a gesture that captured the essence of what I wanted to do with the design of the house in response to the setting. I found music to reinforce the gesture and played it over and over as I did the drawings. I experimented with engendering particular feelings through the orchestration of space, shape, scale, light, color, texture and view.

My last house was called Cambio, Spanish for change, and it was about the exhilaration of letting go into what was calling. It was a huge success. Just walking into it produced a profoundly personal experience of being enlivened and pulled forward. It was published four times in the year of its completion. I was on the cover of the San Francisco Chronicle Sunday Real Estate section demonstrating the dance gesture that started the design. A thousand people came to the first open house, shutting down Skyline Blvd., and bringing the police. Ten Thousand people walked through it during it's time on the market.

I made what seemed like the most amazing discoveries: I had always imagined that we lived in a world of discrete objects that required force acting upon them to be set into motion. Without effort, nothing happened. Or so I used to think. But then I realized that it was change that was the constant, that everything was already and constantly in motion and effort was required to stop it. We were all exhausting ourselves trying to force things to stand still and remain the same because we were afraid of the uncertainty that came with change. All we need do was to let go and stop trying, and things would happen. That led to the idea of aligning myself with what was already in motion and moving with it, rather than trying to impose some sort of stasis on the world. And that in turn led me to become aware of the whole incessant inner commentary of my mind with its artificial distinctions and moral judgments — a pathetic and feral little creature darting around in the shadows concerned only with its own survival.

I considered for the first time that enlightenment might be a possibility. That time was an illusion guaranteed to produce suffering. That everything was contained in this very moment. I started to allow things to happen. Turning towards rather than away from both the light and the dark. I spent the Fourth of July with my sons in Yosemite staring at Vernal Falls, watching the free-flowing river cascade over the cliff, and fall hundreds of feet onto a giant bolder below and had the epiphany that ended my marriage. I was the water. Marina was the rock. Change and stasis. Complimentary but essentially and profoundly incompatible. I let go into the flow, left her in New Mexico and returned to Oakland.

I started smoking dope again. I read books on Zen Buddhism. I went out to bars like I hadn't done in 30 years. I took a mistress twenty years younger than me. She was wild and unpredictable and lived on a boat on the Bay. We hung out in Oakland’s Black blues bars, drank, danced, threw jealous fits and furniture at each other, and screwed like our lives depended upon it. I started doing a semi-spiritual dance practice in Marin County every week that produced personal insights, a tribal affiliation and the deepest, most meaningful communal interactions I've ever known. I met a novelist and poet at a workshop at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur. We had a huge fight in the lunch hall about whether Ophelia had betrayed Hamlet. That led to a five-year tumultuous and wonderfully well met relationship that we are still wrestling with. I started writing. When she threw me out, I moved to Point Reyes and walked the land feeling the spirits at work there, feeding my intuition…and waited.

Art Busse… transforming the way you feel through inspired building design. Link

Art Busse: Facebook. Link

Love on the Downslope…

by Art Busse

Tracks in the Snow…,

by Art Busse

Stranger at the Door,

by Art Busse, The Humanist, November/December 2012. Link

Fathers and Sons, a film by Don Lenzer, 1969. Link.