April Third Movement

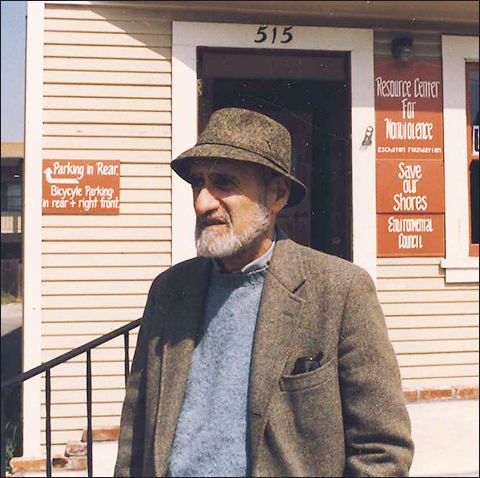

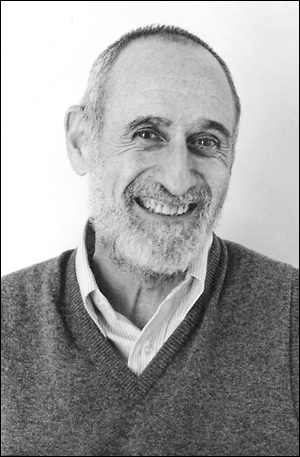

Ira Sandperl

Ira Sandperl, a pacifist and self-styled Gandhian scholar who mentored folksinger Joan Baez, was a political ally of Rev. Martin Luther King, became the first employee of the renowned Kepler’s Bookstore, and introduced a generation of draft-age men to nonviolence during the Vietnam War, died on April 13 at his home in Menlo Park, California. He was 90 years old.

An ardent follower of the principles of Mahatma Gandhi from the late 1940s, Mr. Sandperl met Ms. Baez at a Quaker meeting in Palo Alto in 1959 when she was a senior in high school. The two developed a deep bond and shared a number of political causes. In 1965, Mr. Sandperl helped Ms. Baez found The Institute for the Study of Nonviolence in Carmel Valley, California and became its first president. The organization had a lasting influence on both the civil rights and antiwar movement into the mid-1970s. For a period, Dr. King would send members of his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), to the Institute for training in nonviolent organizing tactics.

I began accompanying Ira to places where he spoke,

Ms. Baez wrote in her autobiography, Daybreak. I heard more about Gandhi, love and nonviolence and a brotherhood of man, which he said didn’t exist yet.

In 1966, Mr. Sandperl accompanied Ms. Baez to Grenada, Mississippi, where they joined Dr. King in a campaign to help desegregate local schools. Two years later, in January 1968, Dr. King visited Mr. Sandperl and Ms. Baez in Santa Rita prison, where the two were serving 45-day sentences for sitting in at the Oakland, California draft induction center. Dr. King said he made the visit because they helped me so much in the South.

Mr. Sandperl also joined Ms. Baez in the Free Speech Movement sit-ins at the University of California at Berkeley during the student occupation of the administration building in 1964.

Mr. Sandperl became a national figure during the antiwar movement of the 1960s, speaking and organizing nonviolent opposition to the war. “Ira was the opening chapter,” said David Harris, who came to Stanford University in 1963 and first heard Mr. Sandperl in his freshman dormitory. Mr. Harris became Stanford student body president in 1966, later married Ms. Baez, and gained national attention when he went to jail for refusing induction in 1969. Mr. Harris, Ms. Baez and Mr. Sandperl toured college campuses together in 1968, encouraging draft resistance.

Mr. Sandperl was invited in the Fall of 1970 along with civil rights leader Rev. Ralph Abernathy to bring the message of nonviolence to Kent State University following the killing of four student protestors by Ohio National Guard in May 1970.

Profiled in an essay by writer Joan Didion in 1967, the Institute for the Study of Nonviolence created local controversy when it first opened in Carmel Valley, but attracted a stream of political novices and veteran activists, as well as celebrities such as folksinger Judy Collins and the Beatles. In her autobiography, Ms. Collins described visiting Ms. Baez and attending a class given by Mr. Sandperl, after which Ms. Baez said: Here’s where I really belong. The music is just what I do to support the school, right Ira?

Mr. Sandperl continued to be politically active through the 1990s. During much of 1977-78, he lived with his third wife Molly Black in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, working with the Irish Peace People.

Ira Sandperl was born on March 11, 1923 in Saint Louis, Missouri, and raised in a Jewish household by Harry and Ione Sandperl. His father was a surgeon and his mother was a follower of Norman Thomas, leading Mr. Sandperl early on to be exposed to both socialist and pacifist ideals.

He attended Stanford University during the Second World War. He was not drafted because he had contracted polio as a child.

Although he had been exposed to his mother’s pacifist ideas as a child, Mr. Sandperl dated his commitment to the teachings of Gandhi to a happenstance encounter after the Second World War. He was walking past a bookstore when he saw a book with a photo of Gandhi on its cover. He went in, and although he did not have the money to pay for the book, the clerk said, Well, if you want this book on Gandhi, I know you will come back to pay for it later.

Mr. Sandperl did, and became a self-described Gandhi scholar.

In 1955 he was hired as the first employee of Kepler’s Bookstore in Menlo Park, California, where he would work on and off until retiring in 1988. Founded by his friend and WWII conscientious objector Roy Kepler, the bookstore was one of the first of a new genre of bookstores that sold paperbacks. Kepler’s was profiled in the 2012 book, Radical Chapters, by Michael Doyle. Mr. Sandperl, who was extraordinarily well-read, was a fixture behind the cash register for many decades. He would engage customers on political topics as well as advice on literature that ran the gamut of classics, poetry, fiction and history.

People would confuse me with Roy,

Mr. Sandperl said in an interview several years ago. I would be holding forth at the counter while Roy would be sweeping up or cleaning the toilet in the back.

Among the constant stream of visitors to Kepler’s were visitors like Ken Kesey and future members of the Grateful Dead. Mr. Sandperl recalled being driven to distraction by guitarist Jerry Garcia and his friends, who several years before starting the Dead, were fixtures at the bookstore and would practice endlessly many nights in the coffee house that was part of the store. Mr. Sandperl recalled phoning Mr. Kepler to ask if he could throw them out because he disliked their music, but Mr. Kepler told him they were harmless.

Before starting the Institute, Mr. Sandperl taught at the Peninsula School, an alternative elementary and middle school in Menlo Park. He co-taught the 7th grade class during his first year in 1960 and then taught creative writing until 1965. One of his classes voluntarily met on additional Saturday mornings because he was reading Tolstoy’s War and Peace aloud to them and the class was enthralled.

Mr. Sandperl was the author of the book, A Little Kinder, published in 1974 with an Introduction by Joan Baez. San Francisco Chronicle columnist Art Hoppe called the book fascinating and deeply enriching reading

from a highly intelligent, extremely well-read, warm, gentle, loving and dedicated human being.

Mr. Sandperl was married three times, and is survived by two of his former wives: Susan Robinson of Paso Robles, California, and Molly Black of La Honda, California; and by two children from his first marriage to Merle Sandperl, Nicole Sandperl, of Aptos, California, and Mark Sandperl, of Placerville, California. He also leaves behind several thousand treasured books that encircled him in every room of his home.

Throughout his life Mr. Sandperl was known for his self-deprecating sense of humor and for saying on occasion, Gandhi, the rat! He ruined my life!

John Markoff is a lifelong friend of Ira Sandperl’s, a New York Times reporter, and author of the 2005 book What the Dormouse Said.

Nonviolence Champion Ira Sandperl Dies at 90

Ira Sandperl, who devoted his life to the cause of nonviolence in human affairs, lived in a one-bedroom apartment in Menlo Park for his last decade, a place within walking distance of Kepler's bookstore, friends said. But if he wanted a book, he didn't need to walk anywhere. He had bookshelves in every room, including the pantry and the kitchen, said David Christie, a friend who helped him move from Palo Alto in 2003. Mr. Sandperl shared his apartment with 4,000 books.

The word multi-faceted may express something of the spirit of Mr. Sandperl. He was a disciple of Gandhian nonviolent resistance, a mentor to folksinger Joan Baez, an associate of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and civil rights leader Ralph Abernathy, Kepler's first employee, a creative writing teacher at Peninsula School (and out-loud reader of Tolstoy, whose work he loved), a Cafe Borrone regular, and a profound influence on those who encountered him. He died Saturday, April 13, at home surrounded by friends and his books. He was 90.

Visiting him was like hanging out in a private library,

Mr. Christie said. Mr. Sandperl was self-deprecating, a great storyteller and spent a lot of time telling stories, many about the antiwar and civil rights movements, Mr. Christie said. He was incredibly well acquainted with just everybody you've ever heard of and many people you've never heard of.

Mr. Sandperl, with Joan Baez and Roy Kepler, had been arrested and jailed in the 1960s at an Oakland sit-in to stop the draft, and used the experience to help people understand the value of being a thorn in the side of the machine,

including coping with jail, Mr. Christie said. In one account, Mr. Christie said a stranger once asked Mr. Sandperl about surviving jail, peppering him with questions and eventually driving him to the airport. He forgot about the encounter until seeing the stranger—Daniel Ellsberg—on the front page of the New York Times. Mr. Ellsberg had arranged the revelation of a U.S. Department of Defense classified history of the Vietnam War known as the Pentagon Papers.

Mr. Sandperl told Mr. Christie that he had prodded Dr. King to take more radical positions, including opposing the Vietnam War, which Dr. King eventually did. Here he is, a self-taught Gandhi scholar and bookstore employee telling Martin Luther King what sort of public ideology he should embrace,

Mr. Christie said. Now, given the stature of Dr. King, it's almost laughable.

Ira was very much a provocateur

and embodied Gandhi's view that there's nothing passive about nonviolent resistance,

Mr. Christie said. He spoke his mind. His friendships could alternate between being on—and not on—speaking terms.

Mr. Christie recalled an exchange he once had. Ira,

he said, you got sharp words for everybody on the planet except Gandhi and Martin Luther King.

Mr. Sandperl replied, I've got plenty of sharp words about Martin Luther King.

But April 4, the anniversary of Dr. King's assassination, was always a hard day for him.

Under hospice care at home, having only Medicare and Medi-Cal to rely on, Mr. Sandperl took the edge off. He made very, very strong bonds with two or three of the caregivers, and those people kept coming back,

Mr. Christie said. Those caregivers were a grace note in the last days of his life. He had the good fortune of dying at home surrounded by his books. … He eked out personal independence and he preserved it to the end.

Married three times, he is survived by two former wives, Susan Robinson of Paso Robles and Molly Black of La Honda. Other survivors are two children from his first marriage to Merle Sandperl: Nicole Sandperl of Aptos and Mark Sandperl of Placerville.

A Brief History

Ira Sandperl,

by John Markoff, Friends of Ira Sandperl (www.irasandperl.org). Link

Nonviolence Champion Ira Sandperl Dies at 90,

by Dave Boyce, The Almanac, April 16, 2013. Link

What the Dormouse Said: How the 60s Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry, by John Markoff, Penguin Books, 2005. The author is a lifelong friend of Ira Sandperl’s and a technology reporter for The New York Times.

A Little Kinder, by Ira Sandperl, Science & Behavior Books (1974).

Radical Chapters: Pacifist Bookseller Roy Kepler and the Paperback Revolution, by Michael Doyle, Syracuse University Press (2012).

Antiwar activist Ira Sandperl dies,

by Sam Whiting, SFGate, April 19, 2013. Link

Ira Sandperl Celebration of Life, 1923–2013

, held June 2, 2013. Video created and donated by Resource Center for Nonviolence (www.rcnv.org). YouTube Link

Friends of Ira Sandperl (www.irasandperl.org). Link