April Third Movement

Eliezer (Eli) Joaquin Risco Lozada

Eli Risco was an important part of the early anti-Vietnam War movement at Stanford

Eli Risco (Eleizer Risco Lozada) was an important part of the early anti-Vietnam War movement at Stanford, and we had lost touch with him after he went off to join the Farmworkers, though we heard that he had been kicked out of the UFW in a spat with the leadership.

Risco was one of the (five? six?) graduate students who stood in the lobby as we left the first Stanford teach-in on Vietnam (1963?), holding signs that said, Support the Viet-Cong.

They supplied the anti-imperialist understanding that provided the healthy polarization of the early movement and moved it on: Keith Lowe, Charlie Li, Ken Mills, Risco, and (if I remember correctly) either Anatole Anton or Jim Sattler.

This champion for migrants opened health clinics, started Chicano studies at Fresno State

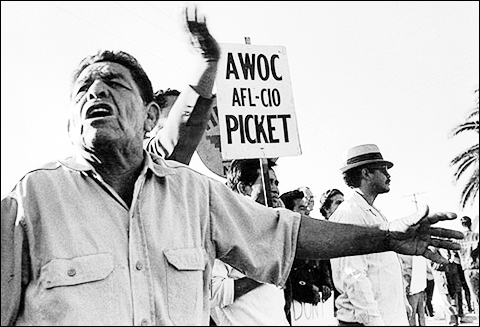

Eliezer Joaquin Risco Lozada, known by many as “Risco,” improved health care, working conditions and education for migrants throughout the central San Joaquin Valley and California. The Fresno man helped Mexican Americans by rallying with labor leader and civil rights activist Cesar Chavez, leading the first Chicano studies program at Fresno State, opening rural health clinics in the Valley, and later becoming an Episcopal pastor.

His calling was to help people,

says daughter Ishlatiya Risco-Lambert, and that’s what he did his entire life.

Mr. Risco died June 15 at the age of 80 in Fresno.

He fled his homeland of Cuba as a young man to avoid imprisonment for protesting leader Fidel Castro. He made his way to L.A., where in the 1960s he served as editor of La Raza newspaper and helped plan student walkouts protesting unequal conditions in schools – activism that landed him and others in jail for conspiracy to disturb the peace. He helped Chavez organize the iconic 1966 march from Delano to Sacramento to protest working conditions of farm workers.

Gilbert Padilla, a former United Farm Workers vice president, remembers him as a good human being

— an intelligent, friendly and hard-working man who never complained.

He was that guiding light—the spiritual guiding light—of this movement.

—Arcadio Viveros

Mr. Risco’s passion for social justice resulted in an offer to teach at Fresno State, where he led the university’s first La Raza Studies program in the late 1960s. It was abruptly cut in 1970 but later reinstated and is now called Chicano and Latin American Studies. Mr. Risco’s successor at Fresno State, Alex Saragoza, now professor emeritus of Chicano/Latino Studies at UC Berkeley, applauded his work as an educator.

His broad knowledge of Latin America brought a broad lens to the understanding of Latinos in the U.S. that was unusual at the time,

Saragoza says. Risco was very dedicated to the effort to build the program in the midst of a difficult, complicated period for the development of La Raza Studies-type academic units in California specifically, and in the U.S. in general.

After La Raza Studies was cut at Fresno State, Mr. Risco and other Fresno State faculty and students established a new college, the now-closed Colegio de la Tierra in Fresno, which offered similar courses.

Soon after, Mr. Risco left his work in education to become a leader in health administration, securing federal funds for the medically indigent and helping open a number of rural clinics in Fresno County—including Sanger, Kerman and Mendota – through his work with Chicanos in Health Education and Planning, Sequoia Community Health Foundation, United Health Centers of the San Joaquin Valley and the California Rural Health Association.

Risco was the thinker, the motor behind all these ideas,

says friend Arcadio Viveros, who worked alongside him as a fellow educator and health administrator. “He brought a lot of resources.

Viveros recalls his friend’s penetrating look

when deep in thought. He would look into your soul. … I would have to stop meetings many times and ask him, ‘Risco, what’s on your mind?’

Later in life, Mr. Risco helped those in need as an Episcopal priest.

“He reached one of his goals – ministering to the poor,” Viveros says.

His entire life has always been about helping people.

—Ishlatiya Risco-Lambert

Mr. Risco led services at Santa Margarita Episcopal Church before moving to the Bay Area to work alongside his late wife, a correctional officer, as a prison chaplain at San Quentin Prison until her retirement, when the couple moved to Tecate, Mexico. Mr. Risco continued serving as a pastor there until his wife’s health declined and they moved back to Fresno to be closer to their children.

Gloria Hernandez, a friend and fellow activist, recalls Mr. Risco as kind and humble. His legacy, she says, is the reminder to “work harder and make sure we reach out and help others.

I think his unselfish love for the community is what kept him going.

Eli's survivors include his daughters. Ishlatiya Risco-Lambert, Tonatzin Risco and Xochi Risco; his son Tlacaelel Risco; and several grandchildren, great-grandchildren, nieces and nephews.

Eliezer Joaquin Risco Lozada’s passing marks a watershed in the Chicano movement

Eliezer Joaquin Risco Lozada’s June 15 passing marks a watershed in an important, not only historical, but cultural psyche of Chicano movement people who operated on this universal truth: You win the hearts and minds of the citizenry not by the barrel of the gun, but the Mahatma Gandhi, Cesar Chavez, Martin Luther King universal truth that the pen is mightier than the sword.

I can’t say I knew Risco

very well, but I had the pleasure of debating and absorbing knowledge from him in a platonic level. In the late 1960s, as a brash student activist, I listened to his mostly gems of opinions about resources and the practical insider methodologies, vis-à-vis government, for funding of community needs. We students were blown away by his extensive awareness of reality existential politics. He certainly had a pedigree and a charm like no other.

Risco, as we knew him, clearly will be dearly missed by many community people, not only by those to whom he dedicated his works, but also, with sadness, by his children. He was certainly ahead of his times on health care issues. And as an Episcopal minister, surely, he guided those with troubled souls toward enlightenment.

This champion for migrants opened health clinics, started Chicano studies at Fresno State,

by Carmen George, The Fresno Bee, June 23, 2017. Link

Letter to the Editor, from Jess Sanchez Barroso, Fresno, The Fresno Bee, July 1, 2017 Link

David Ransom, personal communication.