April Third Movement

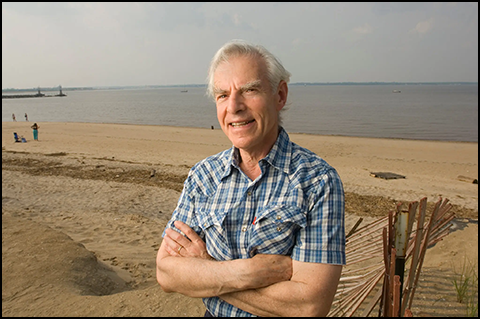

H. Bruce Franklin

In the Matter Of H. Bruce Franklin

H BRUCE FRANKLIN is not only a scholarly authority on Herman Melville but also a member of the central committee of an armed revolutionary organization called Venceremos, a militant who keeps a shotgun handy to the front door of his house, and an unrepentant Marxist‐Leninist‐Maoist. He is, furthermore, rumored to have committed various politically inspired acts of violence, to have trained Mexican‐Americans in guerrilla warfare in the hills above Palo Alto and to have supplied the Black Panthers with explosives. (He has denied these latter allegations, and no proof has been forthcoming from his accusers.)

Just about a year ago, Richard W. Lyman, the president of Stanford University, where Franklin had been teaching as a tenured associate professor of English, set in motion a process that he hoped would lead to Franklin's dismissal for “substantial and manifest neglect of duty.” Early this month, a faculty hearing board brought in both the expected verdict of guilty and the unexpected recommendation that Franklin be fired immediately on three counts of having incited “disruptive” behavior on the campus.

The Franklin case was sure to have repercussions throughout the academic world, for it was not only the first firing of a tenured professor in Stanford's history, but also the only such dismissal at a major university since the Joe McCarthy era. (As we shall see, however, tenured teachers are not infrequently fired from jobs at less prominent institutions.)

When I first came down to Stanford, about two months ago, to look into the Franklin case, I discovered a common opinion among faculty people that the case was really sui generis, something unto itself that had little connection with broader considerations of tenure either at Stanford or elsewhere. As one professor of law told me, “I don't see any reason why somebody who acts in a disruptive and disloyal way toward his employer can't be fired by the employer just as in private industry.” He went on to argue, in effect, that Bruce Franklin was simply a bad fellow who had to be got rid of and that his case had little to do with legitimate issues of academic freedom.

BUT the Franklin case cannot stand by itself. First, it would seem to spell hard times ahead for young, radical, activist professors elsewhere, even though they may have tenure. Second, it can hardly be considered apart from the broader questions of tenure that are very much alive at colleges and universities throughout the country, as they are at Stanford. The issue is less inflammatory than it was 20 years ago because the current pressure on classic ideas of tenure comes not from neo‐McCarthyites but from sober administrative types, often scholars themselves (which is the case at Stanford), who must cope with the practical consequences of the tenure system. These consequences often are—from the administrator's viewpoint at any rate —truly difficult and troublesome, even though they are seldom highlighted by such dramatics as in the Franklin case.

At Stanford, 72 per cent of the faculty in arts and sciences is tenured, which is perhaps the highest percentage at any major university. As President Lyman recently pointed out to an alumni group, this leaves little maneuvering room in the hiring and promotion of young faculty people. “There is sharp worry among our current junior faculty,” Lyman told the alumni, “who can see the handwriting on the wall, and who do not see how we can avoid extruding many of them from the university when the six‐year probationary period for tenure is up. There is understandable concern among the senior faculty, who do not want to preside over a massacre of the innocents, but do not want to promote so many to tenure that there is no room in the lower decks of the ark for fresh young minds. I cannot tell you how we are going to square this circle…. “ (It must also be noted that the situation at Stanford is made more painful by the fact that the university is currently suffering from a severe financial bind.)

Given this real concern over a genuinely difficult issue, not only at Stanford but elsewhere, it is, however, a curious phenomenon that when an actual tenure case comes to the surface, as it did with Bruce Franklin, the professor whose job is under attack is rarely accused of unprofessional behavior growing out of such deficiencies as galloping paranoia, plagiarism, a weakness for female students, alcoholism or even simple incompetence in the classroom. (As one Stanford professor put it to me, “What happens in any institution to the just plainly incompetent or prematurely senile people is that everyone grits their teeth and puts them upstairs or in a corner and tries to get on by.”) What in fact often happens is that the subject of a tenure case turns out to be a teacher of acknowledged skill and personal rectitude who is also a social or political nonconformist or at the very least an unaccommodating personality.

In early December, while the faculty board was studying the testimony in the Franklin case, two other widely different but instructive tenure cases came to light at schools somewhat less visible than Stanford. At Virginia State College, a largely black institution, a tenured professor of languages named Filimon D. Kowtoniuk, who is a refugee from the Ukraine, was fired for “unprofessional conduct.” Professor Kowtoniuk's troubles seem to have arisen from his anti‐Communist activity and his resistance to campus demonstrations opposing the Vietnam war, the Cambodian “incursion” and the killings at Kent State, rather than from any lack of competence as a teacher of German and Russian. At Fairfield University, a Jesuit institution in Connecticut, a tenured theologian named Augustine Caffrey was also fighting for his job. Professor Caffrey's offense was that after leaving the Jesuit order (with permission), he had announced to his students that he had become a religious agnostic. Professor Kowtoniuk has declared his intention of leaving the Virginia State campus; Professor Caffrey has, surprisingly, been returned to good standing by the trustees, who, with the support of the faculty, overruled Fairfield's president. (A cynic might argue that Fairfield's eligibility to receive Federal funds was perhaps a stronger operative factor than a passion for religious

BRUCE FRANKLIN'S case falls somewhere in this genre, for, in a manner of speaking, he was an aggressive unbeliever in a community of believers, and a direct clash was bound to come. Nobody, however, attacked his competence. He was a popular and effective teacher. Fred Mann, the editor of The Stanford Daily, a slender young man with long, reddish‐blond hair and beard, told me, “For people who've taken his classes who haven't been steered away from him by his radical reputation—he's probably been one of the most interesting, if not the most interesting, professors on campus. His classes were very lively and he was always direct in trying not to trample on people's feelings. He stated his point of view openly and listened very attentively to everybody else's point of view and then responded.” (Student admiration of Franklin was not universal. Larry Liebert, another Daily editor, recalled that during the hearing, “in one case Franklin asked a student what he thought about academic freedom in his class. The student said it wasn't too good because he felt there was a kind of informal MarxistLeninist line.”)

Certainly Franklin's scholarly performance has been an admirable one. Since 1964, he has published three books on Herman Melville, a critical introduction to a collection of Hawthorne's works, and a scholarly book on science fiction. Another book on Russian and American science fiction will be published soon. Since the age of 31 he has been a tenured faculty member of the most prestige‐laden private university in the West. In 1970 he was unanimously recommended for promotion to full professor by the full professors in the English department. (The recommendation was turned down on grounds that he had not served out the mandatory time in grade.)

Franklin is a rather short, slightly built man, dark‐haired and dark‐eyed, who looks younger than his age and who in private conversation speaks quietly, carefully and humorously in a voice that holds echoes of his native Brooklyn, where he was born into a family unmarked by affluence. His social manners are gentlemanly and he can exert a considerable boyish charm, but he is not what Californians think of as a Stanford type.

Since it was organized in 1891, and until very recently, Stanford's image was that of a finishing school for the offspring of California's rich and near‐rich, and its spiritual models have been the more ivied of the Eastern universities. Isolated on a far‐flung suburban campus of low build ings with red‐tile roofs, Stanford students lead comfortable and pleasant lives but have no opportunity to enjoy the bookstores, restaurants and Bierstuben that give, say, Harvard and Berkeley much of their flavor. Like graduates of Yale and the Harvard Business School, Stanford graduates have tended to enter the world of established business. Even after the impact made by such disturbers‐of‐thepeace as Franklin, David Harris and their followers, and in spite of its academic excellence, Stanford is still, politically and socially, pretty much an island unto itself, a magic island which students and faculty seem to believe is the best of all worlds

.“When something like Bruce Franklin hits, it hits very, very hard because there's no context into which he can be placed,” I was told by William M. Chace, an assistant professor of English “He was truly like a man from Mars for most of the people here. He had a hard time making them believe he's even part of the human race.”

It was not, consequently, surprising that in the Franklin case, matters of substance became thoroughly confused with matters of style, and that the formal charges against Franklin were only tangentially related to matters that had made him non grata to the administration as well as to many other people on campus.

THE formal charges went back to Jan. 11, 1971, when Henry Cabot. Lodge appeared as a speaker at a conference organized by the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, which has a reputation for political conservatism. The audience had apparently been packed with unfriendly hecklers, for when Lodge rose to speak, Dinkelspiel Auditorium was filled with derisive cries (“Pig! War criminal!”) and then with rhythmic shouting, chanting and clapping. Lodge had to stop, and the program was canceled. Franklin was present in the audience and freely admitted to having uttered some unfriendly comments. Whether or not he had anything to do with organizing the demonstration remained a matter of dispute.

A week later, President Lyman, a 48‐year‐old Harvardtrained historian with a reputation as a firm administrator, wrote to Franklin, charging him with the responsibility for silencing Lodge and telling him that as punishment he would be suspended for a quarter without pay. Franklin fired back an open letter notably lacking in humility. It began, “To the Chief Designated Agent of the Board of Trustees of Leland Stanford Junior University, Heirs of the Family Who Stole This Land and the Labor of Those Who Built Their Railroad, War Profiteers and Rulers of the U. S. Empire” and was signed “In the spirit of Nguyen Van Troi/Power to the people!/Bruce Franklin/ Central Committee/Venceremos.” (Nguyen Van Troi, Franklin told me, tried to assassinate Robert McNamara in Saigon in the early 1960's. “I wonder if Lyman looked him up?” he asked rhetorically.)

TWO weeks later, Franklin was again in the headlines. The invasion of Laos by American and South Vietnamese troops, which was reported on Feb. 8, stirred up antiwar sentiment at Stanford as it did elsewhere. The attention of the Stanford demonstrators became focused on a building called the Computation Center, where work on a war‐related computer program was known to be going on. Franklin spoke at an antiwar rally at a campus gathering place at noon on Feb. 10. Following the rally, the demonstrators marched to the Computation Center, broke in and shut it down. Franklin himself was not among those who entered.

Police from the local sheriff's office arrived in riot gear and formed a double skirmish line in front of the Computation Center. The demonstrators left the building but stood around outside, confronting the police. A sheriff's officer declared the crowd an illegal assembly. Franklin protested the order to disperse, advised the crowd not to give way, and declared that in any case he was going to stay on as a faculty observer. The police charged, and the crowd scattered.

That evening, Franklin spoke at a rally in the courtyard of the Old Union. Following the rally, there was violence on the campus, during which members of a conservative student group were injured, although it is not clear by whom.

Lyman promptly declared his intention of firing Franklin for a “substantial and manifest neglect of duty and a substantial impairment of his appropriate functions within the university community.” Franklin demanded a formal hearing. Lyman suspended Franklin with pay (the previous disciplinary suspension had yet to go into effect) and obtained a restraining order which kept Franklin off campus except when he was gathering material for his defense. In late March, the matter was put into the hands of a faculty advisory committee of seven full professors. (The hearings, originally scheduled for June, were postponed until the fall, when witnesses would be back on campus.)

Four formal charges were laid before the board. First, Lyman charged that Franklin had “knowingly and significantly” contributed to breaking up Ambassador Lodge's speech. The second, third and fourth charges were that Franklin had “intentionally urged and incited” demonstrators to occupy the Computation Center, to ignore the police order to disperse and, after the evening rally, to engage in “disruptive” behavior.

The hearings, which appeared to the campus community to go on almost interminably and whose transcript eventually ran to more than 4,000 pages, were directed toward Franklin's defense against these four charges. The case was thoroughly complicated by the fact that Franklin had made himself disagreeable to many members of the Stanford community long before the happehings at the Lodge speech and the disturbances in February. There was, consequently, an uneasy feeling among some people on campus that the dismissal proceedings were directed at getting rid of Franklin less for the actions described in the formal charges than for being the person he is—or, perhaps, the person he is thought to be.

HOWARD BRUCE FRANKLIN was born in Brooklyn in 1934 into a family which had lived there for three or four generations. His father worked on Wall Street. “He had the phony title of trader,” Franklin recalled recently, “and his salary was $25 a week plus commissions, which meant we were always living on the edge —we weren't living in real poverty but close to it. We made, you know, these great adventurous moves from one part of Brooklyn to another.” Franklin was an only child.

The first member of his family to go to college, Franklin went to Amherst on a scholarship, majoring in English. He disliked Amherst passionately. “Most of the other students at Amherst seemed to me the most contemptible characters I had ever spent any time with,” he once told an audience of college teachers, to their visible distress. “I despised them from the top of their crew cuts to the soles of their white bucks, mostly hating the smug tweediness in between.” He recalls himself slouching around Amherst in an old torn leather jacket and drawing upon himself the reproaches of the dean for the generally piggish state of his room. But as a student he did well under the guidance of such teachers as Benjamin De Mott, who was the adviser for his senior honors thesis, “An Examination and Evaluation of Changing Moral and Social Perspectives in English Dramatic Literature.” Also, he enrolled in the R.O.T.C. as a stratagem, he says, to avoid being drafted for the Korean war. In 1955, he was graduated summa cum laude, a member of Phi Beta Kappa, and a second lieutenant in the Air

“It took me about a decade to recover from the Amherst experience,” he has recalled. “And I an4 only now beginning to understand what a grotesque exercise in a dying culture and class it was.”

From Amherst, Franklin went on to New York harbor, where he worked as a mate on tugboats for several months, an experience he recalls as having restored “some sense of reality.” He married North Carolina girl, an English major from Duke, and then spent just under three years in the Air Force as navigator and squadron intelligence officer in the Strategic Air Command, in a group which refueled B‐47 and B‐52 bombers.

Due out of the Air Force at the end of January, 1959, Franklin became aware of a regulation (a sort of reverse Catch‐22) that would let him take his discharge 30 days early if he had been accepted by a graduate school whose term started at the beginning of January. Combing through the catalogues of graduate schools, Franklin found that Stanford's term began at the right time. He applied and was accepted. Although he had misgivings about becoming a professional academic, he left the Air Force a month early, bound for Stanford as a candidate for a Ph.D. in English.

As Bliss Carnochan, the English department chairman who came to Stanford from Harvard in 1960, recalls, “When I got here, Bruce was a graduate student, and his reputation was that of a real hot‐shot. Everybody knew about him.” He was a student of the late Yvor Winters, the prickly literary conservative who was then the most noted member of the Stanford English faculty.

IN spite of Stanford's genteelness, Franklin found it a more congenial atmosphere than Amherst. As he once benignly described the Stanford English department, “Most of these well‐off white gentlemen were more interested in writing hooks to be read by their peers than in indoctrinating students with the most sophisticated and upto‐date forms of antiproletarian values. The majority did ‘professional scholarship.’ A few made some pretense of dabbling with ideas. Not one was concerned with the major ideological questions of our century. Not one was familiar with the major ideas that attacked their own beliefs.”

Franklin's political judgment of the Stanford English faculty benefits generously from hindsight. In 1961, when he took his Ph.D. and accepted an unusual offer to stay at Stanford and join the faculty —unusual because new Ph.D.'s are generally driven away from their academic incubators in order to forestall inbreeding—Franklin thought of himself as a Democrat of the Stevensonian cast, and worked for Lyndon Johnson's election in 1964. He has described his political consciousness at that time as a “total ignorance of the relations between literature and class struggle.” He became radicalized, he told me, between 1964 and 1967.

Aaron Manganiello, who is a revolutionary Chicano, or Mexican‐American, recalls that his first meeting with Franklin came in 1965. “I was being thrown off the College of San Mateo campus for selling peace buttons. There was a rally called and two people from Stanford came and spoke. One of them was Bruce Franklin. We pulled practically every student off that campus.”

Manganiello went on: “During the antiwar movement I kept up an acquaintance with Bruce, sort of casual at first. Then he went to France to teach at a Stanford campus there, and when he came back, we found we were of the same political mind.”

Franklin has mentioned the impact of the Vietnam war, the civil‐rights movement, and the black revolution on the process of his radicalization. The year in France, during which he taught at the Stanford campus at Tours and helped found, and became honorary dean of, the Free University of Paris, was the critical experience. “Jane and I became Marxist‐Leninists while we were in France,” he told me. “We'd been quite active in the antiwar movement here, provided some leadership and so on and by the time we left the United States in 1966 we considered ourselves revolutionaries, but we didn't really know what that meant and we hadn't studied any theory to speak of During that year in France we had the opportunity to work with young people from many countries, including Vietnam, who had quite an influence on us. When we came back to this country we were Marxist Leninists and we saw the need for a revolutionary force in the United States.”

Looking around, the Franklins found no existing organization that fitted their beliefs and agenda for action, and so, with friends, they formed an organization called the Peninsula Red Guard, which eventually merged with similar Bay Area groups into an organization called the Revolutionary Union, which lasted until 1970.

WHILE Franklin's radicalization was going on, Aaron Manganiello had broken on ideological grounds with the Brown Berets—the Chicano equivalent of the Black Panthers—and was building up Venceremos as a “multinational” organization that soon included white revolutionaries. Prominent among these was Bruce Franklin, who, with a like‐minded group from the Revolutionary Union (which Manganiello considered “racist and pettybourgeois“), came over to Venceremos on New Year's Eve, 1970, after an eight‐hour meeting to discuss the merger. Franklin became, and still is, a member of the Venceremos central committee.

The document which came out of the New Year's Eve marathon was a five — point manifesto. The first point was national liberation and international revolution; the second, the dictatorship of the proletariat; the third, democratic centralism as an organizational principle; the fourth, the liberation of women. The fifth was armed struggle, and it is here that came the sticking point for Stanford liberals, for by armed struggle was meant the right to bear arms and to use them if necessary. (“The right of the people to defend themselves cannot be taken away by anybody…. Every Venceremos member must learn to operate and service his weapon correctly, must have arms available, and actively teach the oppressed people the importance of armed and organized self‐defense.”)

Every member of Venceremos, Manganiello claims, has at least one weapon available. The organization recommends the M‐1 carbine and the 30.06 rifle, the .45‐caliber automatic and the 9‐mm. pistol on the grounds that, even if a gun‐control law comes, the ammunition for these weapons will probably still be relatively easy to come by. When I asked Manganiello how often they had had to use their weapons, he answered that “during the last three to five months we've drawn weapons on police and been on the verge of a shootout at least once every two weeks.” (How much of this account reflects the romanticism of the armed revolutionary, I do not know.

)“One hundred and ten eyewitnesses were heard and over a million words of transcript recorded.”

THE charges that Franklin has trained guerrillas in the hills go back several years, and have most recently been aired before the Eastland committee. Franklin, who has denied the charges repeatedly, pointed out to me that he is under frequent surveillance and that if any evidence had been discovered by the law agencies who have shown an interest in his activities, he would surely have been arrested long ago. “What they've been trying to do for three years,” Franklin said, “is to find some fact to fit the case they themselves put together.”

The constitutional right of the citizen to bear arms is of course a matter of current debate, with conservatives, leftist radicals and nonpolitical hunters finding themselves unexpectedly in the same boat. In California, it is illegal to carry a loaded weapon in places where it would be illegal to fire it. It is still permissible to keep a rifle or shotgun in one's home or place of business.

Franklin keeps a Remington 12‐gauge automatic shotgun “very available” in his house and has carried it when meeting policemen at the front door. “We often have extra armed security in the house,” he told me. (By “extra armed security” he meant other members of Venceremos, who are called together by an alert system when the police threaten them.) Most recently, about two months ago, “a lot of police came looking for some house‐burglars they said had jumped over our fence. They had all these police out front who demanded to come in and look for this guy. Finally, after we got a lot of people here, we allowed one of them to come into the back yard, under supervision, to look around.”

On the day that I talked to Franklin at his house, he was dressed in a disarmingly pettybourgeois style—a navy blue sports shirt, dark slacks and suede boots. One wrist was wrapped in an elastic bandage, but not, as it turned out, from revolutionary skirmishing. His hair is not notably long. Sometimes his diction bounds disconcertingly from the natural style of an educated young Easterner to the rhetoric of the revolutionary. (He once told a group of scholars, “The heroic struggle of the revolutionary masses of Vietnam throws the lie into the rotten teeth of those who libel and degrade humanity.”)

As we talked, Jane Franklin was pounding a typewriter in another room. The children—Karen, 15, Gretchen, 13 and Robert, 8, were at school. (The older children share their parents’ politics, and “some people have forbidden their kids to play with them.”)

When I asked Franklin how he got along with such nonviolent revolutionaries as David Harris, he replied that “the oppressor feeds on nonviolence.” He went on: “There's the myth, you know, that violence begets violence. With the police we've found that simply to survive we have to be armed and we have to be able to draw on comrades very rapidly in our defense.”

Franklin has been arrested twice, for failure to disperse and for assaulting a police officer. The first charge was dismissed. He was acquitted in the second case after a five‐week trial.

THE seven full professors of the faculty advisory board, of course, officially knew nothing of these more picturesque matters. Meeting in a physics lecture hall, their charge was simply to determine whether or not Franklin had forced Lodge to abort his speech and had “intentionally urged and incited” the other incidents of disruptive behavior. As President Lyman put it in August, “It's no longer a question of opinions, popular or unpopular. It's a question of actions.”

The hearings, which lasted from the last week of September to the first week of November, from 1 o'clock to 6 o'clock, Monday through Saturday, did little to clarify what Franklin had actually done. One hundred and ten eyewitnesses were heard, testifying to conflicting accounts of what had really happened in Dinkelspiel Auditorium or outside the Computation Center or in White Plaza or the Old Union courtyard. One hundred and twenty documents, 230 photographs, and four tape recordings were repeatedly consulted, and over a million words of transcript recorded. The university was represented by a firm of lawyers imported from Los Angeles. Franklin represented himself.

The hearings were eventually regarded on campus as something of a bore although not a complete bore. (“It doesn't speak highly of Stanford, but for a long time Bruce has been our only subject of conversation,” one faculty member told me. “You'd think we could have come up with two or three others.”) The extra hearing rooms that had been equipped with sound systems for the expected overflow were never used. (Yet, when the campus radio sta tion stopped broadcasting the proceedings, there were enough protests to induce it to resume.) There were a couple of incidents of “guerrilla theater.” In one of these, five young men wearing pig masks and sheriffs’ stars were subdued by five members of the audience. Then all 10 actors left the room, shouting “Power to the people!” The proceedings became so informal that, as one observer recalled, “stray dogs wandered in and out, looking for their masters.”

“It became clear to me that, tragically, there was no sensitivity for civil liberties on the Stanford campus.”

Toward the end, a general view was expressed by a Stanford alumnus who told me thoughtfully that although he didn't think the prosecution had made a watertight case, he would on the whole feel a little more comfortable if Bruce Franklin were to be ejected from the Stanford family.

This view of the matter was notably not shared by an interested observer, Alan M. Dershowitz, a professor from the Harvard law school who is visiting Stanford. Dershowitz's involvement in the case provides an acute commentary on the climate at Stanford while the hearings were going on. A small, scholarly looking man of 33 with sandy hair, a red mustache, and gold‐rimmed spectacles, Dershowitz wryly recalls that he had decided to spend his year at the Stanford Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences in writing a book and avoiding any distractions. “I tried my damnedest to stay out of this Franklin matter but it couldn't be done. Literally the first full day I was in residence here at the center in August, I got a call from some concerned faculty. They kept in touch and then I began to get calls from time to time from Mr. Franklin himself. Then there came a time when it became clear to me that, tragically, there was no sensitivity for civil liberties on the Stanford campus. Most tragically, it was blatantly absent among the law school faculty.”

Dershowitz went on, “I've been shocked by the response I've gotten as a result of my involvement in the case. Frankly, I've been made to feel like a Northern lawyer who went down to Mississippi and started speaking out on behalf of the blacks, and the local people said, —Shhhhh, don't mess around, don't stir the natives up.’ “

The brief that Dershowitz prepared with the help of local lawyers for the American Civil Liberties Union (he has served on the A.C.L.U. national board) was essentially the classic libertarian argument directed toward establishing Franklin's right to free speech under the First Amebdment and his right to engage in political conduct that went right up to the very line of permissibility. Its conclusions were that Franklin should not be disciplined in the Lodge affair unless it could be shown that he intentionally tried to cut short Lodge's speech. In the matter of Franklin's arguing with police about their dispersal order outside the Computation Center, the brief found no cause for discipline. Finally, the brief argued that both speeches he made on February 10 — the White Plaza speech and the Old Union courtyard speech—were clearly within the limits of the First Amendment.

I remarked that I'd been struck by the extent to which Franklin seemed to have made it deliberately his business to outrage the Stanford community. Dershowitz looked weary and said, “He outraged me, for example. When I was approached to be involved in the case, I came to the hearing room for the first time and saw a picture of Stalin on his counsel table. I wouldn't dream of sitting at a counsel table with a picture of Stalin. There's only one possible picture that would outrage me more than Stalin's, and that would be Hitler's.”

Dershowitz continued, “there's a sense in the Stanford community that Franklin's a very, very bad person indeed, that he's armed Chicanos, that he's advocated the use of violence and guns against the police, and that he's possibly been involved in the bombing of a house on the Stanford campus. All those things are in the air. What can be proved against Franklin is very different from what people think they know. What can be proved is not much.”

For the most part, the faculty stood aside. “I don't think they saw their own interests involved,” I was told by William Chace, the English professor. “It wasn't at all like the loyalty oath or the McCarthy years.”

Others, including Jack H. Friedenthal, a law professor who last year headed the Stanford committee of the American Association of University Professors, took comfort froth the fact that Franklin's fate was being effectively decided by a faculty group. “The president's powers are in fact very narrowly circumscribed,” Friedenthal told me in explaining why the faculty didn't feel threatened by the administration's move against Franklin. “The advisory board is us. It's our elected people.”

Virtually the only expressions of visceral concern came from small groups of liberals and conservatives. Shortly after the hearings were over but before the verdict was in, a group of politically active, generally leftish professors presented a long brief to the advisory board on Franklin's behalf. Prominent among the 60‐odd signers was Linus Pauling, the Nobel laureate chemist. Charles Drekmeier of the political science department, who had been active in organizing the brief, told me that there had not been any real effort to collect as many signatures as possible. He thought that at the most a third of the faculty of a thousand might be counted on as being sympathetic to a strict construction of Franklin's right to tenure. (This was probably a generous estimate, according to other sources.) Conservatives also submitted letters to the hearing board, most notably in the case of 24 professors in the earth

PEOPLE I had talked with at Stanford had without exception predicted that the hearing board would take a middle course, finding Franklin guilty as charged and punishing him by suspending him for one or two quarters without pay. (“He'll just spend it writing another book,” one professor told me bitterly.) Instead, the board surprisingly found Franklin innocent on the count of interfering with the Lodge speech, but by a vote of 5 to 2 recommended his immediate dismissal on the other three charges, which had to do with the two speeches and the confrontation with the police at the Computation Center. (The recommendation was endorsed by President Lyman on Jan. 9 and passed on to the board of trustees for their concurrence. There seems little likelihood that they will change either the verdict or the dismissal.)

Franklin promptly called a press conference at Venceremos headquarters in Palo Alto. I missed it, but William Chace described to me what he saw on the television screen: “I'd sort of expected in the back of my mind that this would be a crushing blow to Bruce. He's lost his job, he's 37 years old, he has three children. And there he is on television—bright, happy, enthusiastic and winning, with that kind of boyish, impish way he has.” Jane Franklin had stood alongside him, not smiling and carrying an M‐1 carbine.

There was nothing impish about Franklin's reception of the verdict. He said there were lies on every page of the 168‐page report, described the members of the board as “liberal Fascists,” and recommended violence on the campus. When, later, I asked him if he'd really meant this, he said, “Sure. I don't think anything would be going too far. I certainly don't think the people on the advisory board should be allowed to keep teaching their classes.”

Franklin went on to say that he was going to try to raise the money (a minimum of $25,000, he thought) to take his case to the courts, either as a breach‐of‐contract case or, by choice, as a First Amendment case. When I asked if he expected ever to get another academic appointment, he laughed and said, “The main decision as to what I do now is going to be made by the central committee of Venceremos, so we haven't even discussed it yet.”

The reaction on campus was even by Stanford standards unexpectedly mild. The public comments that were made fell into predictable channels. The Daily, which had recommended Franklin's reinstatement, expressed its dismay. The faculty political action group was outraged. Linus Pauling described the verdict as “a great blow, not just to academic freedom but to freedom of speech.” The Student Council of Presidents and the Student Senate warned that “the lid may now be off on repression of political dissent on the campus.” The assistant dean of earth sciences welcomed the dismissal as an answer to “a clear‐cut case of the university's existence being threatened by Professor Franklin's presence.”

Among the people I'd discussed the case with, William Chace told me that he was reading the report and that he had “for the first time a genuine sense of admiration for the intellectual power of the group.” He went on, “I had a sense once that Bruce was our conscience, that while we were drinking our martinis and living in the lap of luxury he was carrying on the fight. I guess I've gotten over that.”

Alan Dershowitz, the visiting Harvard professor, was seriously disturbed. He reported that although the A.C.L.U. had yet to take an official stand, speaking for himself, he found in the report a “lack of sensitivity about free speech.” He went on, “I regard the decision as a frightening one in the sense that it will clearly have a chilling and deterrent effect on what professors think they can say to mass audiences In situations that may be inflammatory: In general, it's going to make professors think twice about speaking out. For Stanfard, that could be a disaster because they aren't accustomed to speaking out anyway.”

TWO days after the verdict, the reaction on campus was described to me by one person as “mild” and by another as “apathetic.” There had been a rally attended by several hundred people and a march on the president's house by about 60 people. There were rumors of planned “trashings” but nothing much happened. The proverbial sigh of relief was almost audible.

In the midst of this general silence could be heard the diminishing echoes of two voices that had spoken up in a way that it was hard for even Stanford to ignore. These were the voices of Donald Kennedy, the panel's chairman, and Robert McAfee Brown, a theologian, who had dissented from the majority recommendation and asked for further suspension as the maximum penalty. They spoke of the “substantial costs in Professor Franklin's loss to the institution … in the form of corrosive effects on academic freedom, and … in terms of lost challenge and the subtle inhibition of dissent.”

Brown described his misgivings with considerable eloquence: “However much I and many of my colleagues may disagree with what Professor Franklin says or how he says it, I fear we may do untold harm to ourselves and the cause of higher education unless, by imposing a penalty short of dismissal, we seek to keep him as a very uncomfortable but very important part of what this university or any university is meant to be.”